Sana Goldblatt, Soldier, 1913-2003

- What was it like to join the war effort as a medical professional?

- What were the medical facilities like during the war?

- What kinds of people did you treat?

- What was it like to work with wounded soldiers every day?

Sana Goldblatt in 1938

Sana Goldblatt, born on Delancey Street in the Lower East Side in 1915, graduated from high school in 1931 and worked hard in the needle trades at five or six dollars a week until 1933. In 1933, she began training as a nurse at Beth Israel Hospital and joined the Young Communist League. Her family by then was living in Brooklyn; she had been coming into Union Square in Manhattan for rallies since she was 14, when she was still in high school.

By 1933, she was meeting with other student nurses to discuss politics and organize a union. The Director of Nursing at Beth Israel called in the FBI to investigate the union and then — on the basis of her political action — refused to recommend Sana for further training. Sana had wanted to study psychiatric nursing at the famous Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. Instead, she stayed in New York and went to train at Bellevue Hospital.

What was it like to join the war effort as a medical professional?

Sana. You read the literature and you knew what was going on. How to apply? There was an ad in the Daily Worker, a place to go, or call or see, and I went down there and was interviewed.

Joe. That’s the procedure. What about…?

Sana. For me. You see that was legitimate. The American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy

Doctors and nurses from the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy departing from New York City

Joe. So you actually got… were you able to get a passport?

Sana. Yes, of course, because we were there for nursing, to help them.

Joe. Oh, humanitarian.

Sana. Right. We had no problem. We didn’t have to climb over the mountains. We went in by train.

Joe. I never thought that or knew that. That’s interesting. How many of you were there? When did you go through this procedure? Do you know exactly?

Sana. I think the end of March or early April of 1937.

Joe. Just to back-pedal a second and then I want to get to this medical life, the procedure was pretty straightforward, as you say, “legitimate.” But as the little girl says in “Somewhere over the Rainbow” [from The Wizard of Oz (1939)], “This is not Kansas!” You were prepared to go to Menninger! But going to Spain at the very least, anybody would ask, were you afraid?

Sana. You know, at 22 you are not afraid. I’d seen life by then, I’d seen death.

Joe. It’s true. You may have been less…

Sana. You are a little more sophisticated.

Joe. You may have been a little less innocent than some of the men that I’ve talked to if you’d been through a major urban hospital plus Bellevue. That toughens a person. If you were to describe nonetheless, it isn’t done casually. Your motive. What made you think that your, let’s assume your best contribution would be…?

Sana. They needed medical staff. That was the thing. That was definitely clear. I had a skill that I could contribute to a cause that I believed in. What else can I say?

Joe. It’s funny. That, as you say it, makes a little more sense to me than some of the decisions of soldiers. I sometimes look at a guy and I want to say, whatever made you think…?

Sana. I know it.

Joe. Kleine mensch, that you with a gun in your hand, who had never held a gun…

Sana. Who had never held a gun, knew no formation, nothing about…

Joe. …could make a difference. Whereas you really knew what you were going to do.

Sana. Right. My grandson who is 14 wrote a paper. Out of the clear sky he came up one day and said, “Grandma, tell me about Spain. I want to write a paper on it.” These kids are not political. They are middle class and all that. I was just so surprised. I helped him. He said, “I’ll come over and I’ll ask you questions.” He had all these questions written down. The first question he says to me is, “Grandma, why did you go to fight in Spain?” I said, “Back up! I didn’t go to fight.” That’s the thinking.

Joe. That’s wonderful, that’s wonderful. It really makes a person pause. Again, I should say that in most of my talks, I’m not that interested, actually, in what people did in Spain. That’s another person’s book, in a way. I’m not a military historian particularly and so I sort of skirt the subject. But in this case I’m interested in where you went and what you did once there. You say you took a train in.

Sana. We went by boat. It was funny because they went by groups. You couldn’t send one or two people so you got a group together. I think I was the second group. The first medical group went earlier, around Christmas time. Then the second group, we had about 14, 15 people. We had a doctor, two male nurses, a bunch of female nurses, a lab technician. I can’t remember everybody.

Joe. A team, actually.

Sana. Yes and no. Whatever they can get. We went by boat to France and from there we took the train to the border. At the border we crossed on another train into Spain and we met Barsky [Dr. Edward Barsky from Beth Israel Hospital, N.Y.] at Villa Paz. Then they were starting to send groups out, radiated from that to other areas wherever they were needed. Wherever the action was. So they went south, they went north, you know.

What were the medical facilities like during the war?

Joe. Did you participate in…?

Sana. I stayed mainly at Villa Paz. Except when I was sent up to the battle fronts.

Joe. Did that happen?

Sana. Well, three or four times. We stayed in action. I can’t remember everything. One was at Teruel [January-February 1938]. I know it was winter and it was snowing.

Joe. What were your facilities at a place like Teruel?

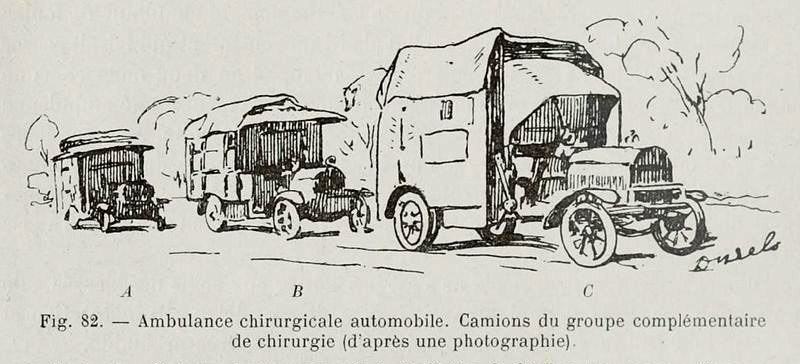

Diagram of an autochir procession from a 1919 French text, Surgical Innovations from the Great War. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Sana. The most amazing thing to me was a big van called an autochir—chir being surgery? [The autochir, or ambulances chirurgicales automobiles, ACA, were built by Renault in France.]

This was a French tremendous thing. It had everything you needed for surgery. Everything. Behind that came trucks with beds, mattresses, sheets, etc. All the stuff you would need for nursing. And behind that of course came the guy who foraged for food. You have to bring all these things along.

I worked with one other woman who was in charge of surgery. She and I managed the whole thing. You could use the van because it had its own generator. They had this big operating room table in the center of it. Everything was outfitted, every space in the wall had a place. For hemostats, for sutures, for bandages, for instruments. Everything had its place so that you could put your hand on anything in this small truck.

Mainly we did not work in the truck. When we got into a city and it was close to the frontline what we did was find a house. One of the places we used was a stable–the house was above the stable, the stable below. That became the surgery. You pulled the table out, you pulled everything you needed out. Even your operating room gowns and mask—everything was in there. So you pulled in and you could start working.

Joe. So suddenly a stable becomes an operating theatre or sufficiently…

Sana. Whatever you needed it for or whatever we could. Then they’d find a place next to it where you could set up your beds and your mattresses and your IVs or whatever you needed right there.

What kinds of people did you treat?

Joe. Were the — let’s call them patients — were they mostly brigadistas? Were they Americans? Did you follow our boys, so to speak?

Sana. Yeah, the battles. But not necessarily.Joe. Strictly speaking, were you a brigadista? Were you in the Lincoln Brigade?

Sana. Yeah. We have been incorporated into the Lincoln Brigade many years ago. You were [in] a Medical Bureau, which is different, but then they decided… anybody who was in Spain…

Joe. So you were basically attached to the American volunteers?

Sana. Yeah. Other people were attached to the Spanish Brigades, depending, you know. The Americans.

Joe. Other Americans were…

Sana. Oh yes, they were all sent over.

Joe. Did you ever see any of your comrades from New York pass through the hospital or throughout the…

Sana. Well, I didn’t know that many.

Joe. You may not have, because your life in New York had been rather…

Sana. It was different. I wasn’t that kind of a party member.

Joe. I mean, that’s right. If you were mostly working, of course, so intensely in the hospital, in New York and not out on the… or necessarily even…

Sana. Selling newspaper or being a functionary. No.

What was it like to work with wounded soldiers every day?

Sana. About 13, 14 months, somewhere around that.

Joe. A full load.

Sana. Well, no, it wasn’t that bad. I could have stayed longer, except that this is always one of my things. I can work with sick patients for about a year, and then I burn out. And I remember saying to Barsky at that time, “Put me in the laundry.” Anything to get away from this. Because after a while you feel the whole world is sick. There isn’t a human begin alive that is well. Anyway, it was after the breakthrough at the Ebro [April 1938]. And he said, “I can’t. You came here as a nurse, you got to work as a nurse.”

Later, when Sana Goldblatt was leaving the country in order to accompany a pregnant British nurse who needed assistance, both women were stopped in Barcelona by guards from the Spanish Republic who detected two suspicious items in their baggage: sheets of German propaganda that Sana was bringing back to New York for the Daily Worker to use as further proof of Nazi complicity in the Franco regime, along with a book on the International Brigades that included a chapter on the “Franco-Belge”—that is, the French and Belgian battalion.

The vigilant and barely literate guards saw the demonic name of “Franco” and put that together with German propaganda and what they took to be Sana’s German name, Goldblatt. The two women were arrested and, given the rough justice of war, might have been tried and shot if their male partners hadn’t intervened. Even their intervention would have meant little without the presence (and presence of mind) of Ernest Hemingway, who was everywhere in Spain, in this case drinking with journalists in Barcelona at the time. Hemingway’s prestige in the Spanish Republic was enormous, and his advocacy liberated Sana and her companion. A year and a half later, Hemingway published his novel of the war in Spain, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Explore more stories: