The author’s first Chanukkah, which was also Shabbat and the day after Thanksgiving 1975, with grandparents Henry, Estelle, and Ethel, her father David, and Sarah, six months old. Photo by Roberta Benor.

By Sarah Benor

My preschool years were conducted primarily in English, but Hebrew also played an important role, appearing in songs and blessings, as well as words inserted into English sentences. At my JCC preschool and summer camp, we sang Hebrew songs like “David, Melech Yisrael” and “Shalom, Chaverim” and Jewish English songs like “Who Knows One?” (“Six are the books of the Mishnah, five are the books of the Torah… one is Hashem”). At home, we recited Kiddush in Hebrew every Friday night. We hunted for “chametz” and chopped fruit and nuts for “charoset” the night before the “seder.” And I called my grandma “Eemie” because she asked my mom (her daughter-in-law) to call her “Eema” (Mom).

I believe this infusion of Hebrew in my early years was instrumental in making me feel that Judaism is a core part of my identity. But it was not until I began researching Jewish languages that I truly appreciated how common this kind of language mixing has been in Jewish communities around the world, throughout history.

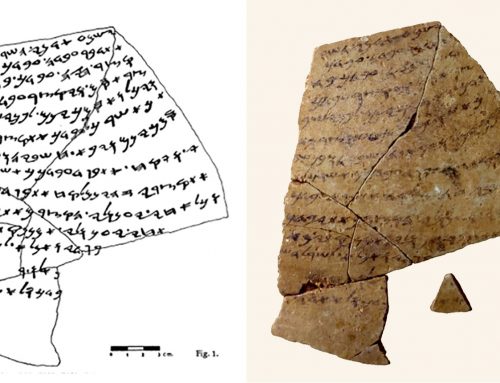

To give just a few examples, Jews in medieval France composed bilingual wedding songs with lines alternating in Hebrew and French. Jews in Modern Italy had a Judeo-Italian version of “Who Knows One?”: “Sei ordini de Miscnà

I rejoiced in my discovery that I, an American Jew, had spent my whole life participating in this millennia-old tradition of speaking a local language with enrichment from our sacred language, Hebrew.

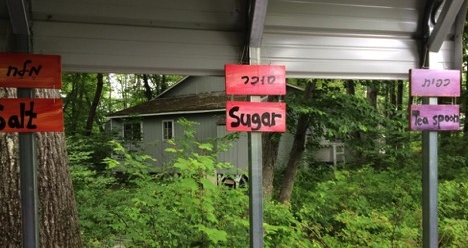

An outdoor cooking area at Moshava IO (Bnei Akiva camp in Pennsylvania) utilizes Hebrew and English words. Photo by Sarah Benor.

Hebrew at Camp

A few years ago, when I began research on language at American Jewish summer camps, I found an environment where Hebrew is infused in much more intensive ways. In addition to Judaic words like “Shabbat shalom” and “tefillah,” I heard sentences like these: “Chanichim (campers), go to your tzrifim (bunks), get your bigdei yam (swim suits), and meet at the brecha (pool).”

Although this is also an example of Jews incorporating Hebrew words into their local language, it represents a new development. Traditionally in Diaspora communities, Hebrew words were used for ritual and communal life; euphemism referring to anatomy, excretion, and death; and secrecy in business and discussions about non-Jews. At many American Jewish summer camps, Hebrew words are also used for camp activities, locations, and roles. This new kind of Hebraized English was possible because of the rise of Modern Hebrew and the connections that American Jews (and their summer camps) maintain to the State of Israel.

Hebrew sign for Chavat Hasusim (Horse Farm) at Olin Sang Ruby Union Institute (Union for Reform Judaism camp in Wisconsin). Photo by Sarah Benor.

I loved hearing the mixing of Hebrew words into English sentences at camp. To me, it seemed like the next level of the Jewish English I heard as a child: campers would feel that much more connected to Hebrew and to Jews around the world, including Israel. But that was not how everyone saw the situation. When I told people – camp alumni, staff, and administrators – that I was researching how Jewish camps use Hebrew, I sometimes encountered negative reactions: beliefs that “camp Hebrew” was “incorrect” or “impure.”

Just as Hebraized English was only possible because of the rise of Modern Hebrew, these criticisms about impurity could also be attributed to contact with the Israeli language. Hebrew had become not only our sacred language and source of Judaic enrichment for our primary language, but also a modern spoken language of day-to-day life in our old-new homeland. Those who were critical of camps’ flagrant mixing of languages, it seemed to me, were privileging spoken Hebrew over the ways Jews have used Hebrew throughout history.

When the organizers of the Hebrew & The Humanities Symposium at the University of Washington asked me to write about my connection to Hebrew, I immediately thought about the use of Hebrew words in Jewish languages, including the one I speak, Jewish English. After reading several of the other essays in the series, I realized that mine would be anomalous – I would not be focusing on Israeli literature or culture. I could have written about my many experiences with Israeli Hebrew: as a student at a Hebrew-oriented Jewish day school, in college Hebrew classes, during the year I spent in Israel, and as an academic who interacts regularly with Israeli colleagues.

But to convey how I most deeply connect to Hebrew, I felt it was important to write about Hebrew infusion in my American Jewish life. That type of Hebrew – songs, blessings, and words peppered into English – connects me not only to my special language, but also to Jews around the world and throughout history.

Sarah Bunin Benor is Associate Professor of Contemporary Jewish Studies at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. She is the author of many articles on language and identity, as well as Becoming Frum: How Newcomers Learn the Language and Culture of Orthodox Judaism (Rutgers Press, 2012). She is founding co-editor of the Journal of Jewish Languages, and she created the Jewish English Lexicon.

Sarah Bunin Benor is Associate Professor of Contemporary Jewish Studies at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. She is the author of many articles on language and identity, as well as Becoming Frum: How Newcomers Learn the Language and Culture of Orthodox Judaism (Rutgers Press, 2012). She is founding co-editor of the Journal of Jewish Languages, and she created the Jewish English Lexicon.

[…] Continue Reading […]