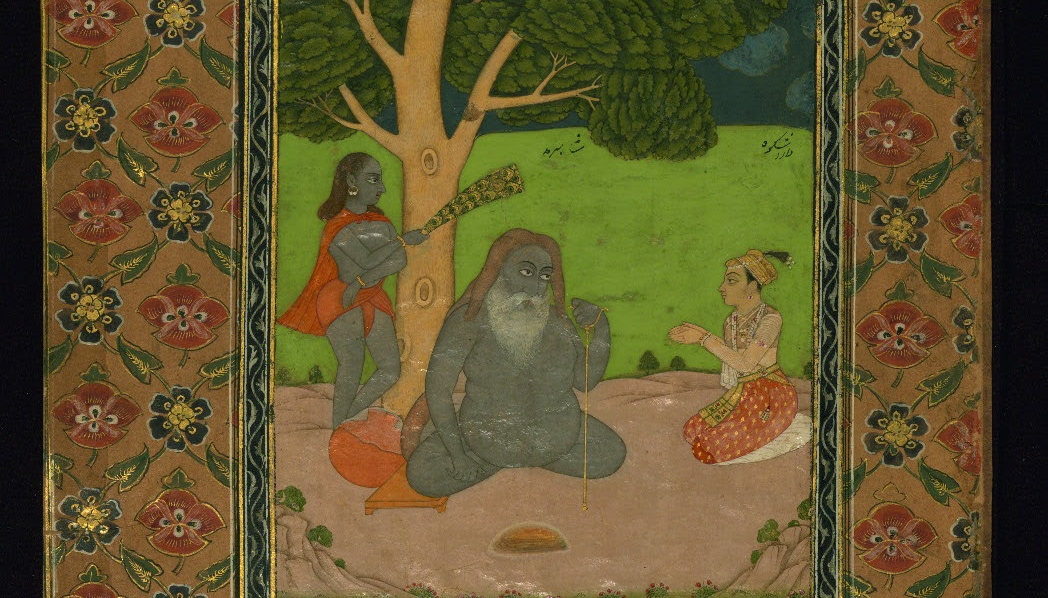

A depiction of the Persian Jewish poet Sarmad Kashani, who is believed to have translated the Torah into Persian. Image courtesy of the Walters Art Museum.

By Sasha Prevost

When my father heard the news, he was so excited that within an hour, he had emailed, texted, and called me: “Sasha, I heard a story on NPR about a professor who just won the MacArthur Genius Grant! She studies medieval Hebrew and Arabic texts, kind of like you, right?”

Spending years steeped in medieval texts and mystical poetry has rich payoffs of its own, but feeling as if one’s topic is torn from the headlines isn’t always one of them. Princeton professor (and UW Jewish Studies’ own former Hazel Cole fellow) Marina Rustow’s MacArthur Genius Grant for her work on the Cairo Genizah was a victory on multiple levels. Most obviously, it was a recognition of Rustow’s efforts to bring to light a vast collection of Jewish texts and fragments found in the storeroom (the genizah) of Ben Ezra Synagogue in old Cairo. With this news, medieval Jewish texts, especially texts from the Islamic world, received a much-deserved moment in the limelight. For aspiring scholars like myself, particularly those of us who work on less-known corners of the Jewish world, it also granted a moment of legitimacy, an opportunity to paste that NPR link into an email to a curious family member or classmate and say, “I do something like this.”

With interests at the intersection of South Asian Studies, Persian Studies, and Jewish Studies, it can be difficult to shrink my research topics to an elevator pitch. Indeed, I’m interested in individuals and time periods who often fall through the cracks. On the Jewish side of things, I’m fascinated by the world that flourished in between the period of classical Rabbinic texts and the coming of modernity. Geographically, I look at Jewish communities whose existence is all too often forgotten: the Jews of South Asia and the Persian-speaking world. In recent years, Jewish Studies and Jewish communities have become increasingly aware of the heavy focus on Ashkenazic Jews, what’s sometimes dubbed “Ashkenormativity.”

As a burgeoning center for Sephardic Studies, the UW Stroum Center is part of a movement to change this. Still, all too often the Jews of the Arab world, let alone Persian or Indian or Chinese Jews, are erased from the story, or at best acknowledged as exoticisms. I’m interested precisely in what these communities can tell us about the range of premodern Jewish identities, and the limits of religious identity itself. Thus, it’s the religious iconoclasts who captivate me, characters who broke the mold, who occupied unusual or uneasy places between religious, communal, or even sexual categories. Through them, I dig into the eclectic and messy side of history.

Who was Sarmad Kashani?

Born around 1590 to a Jewish merchant family in Kashan, Iran, Sarmad supposedly received a thorough Jewish education, but later converted to Islam after studying under the preeminent Islamic scholars and philosophers.

Around the age of 40, he underwent what we might now term a midlife crisis. While traveling in the subcontinent on business, his career took an unexpected turn: he fell madly in love—spiritually, says the tradition—with a young Hindu man, Abhai Chand. This passion inspired him to cast aside all manner of social conventions, including, quite literally, his clothing. In the tradition of naked Indian yogis or renunciants, Sarmad went about naked, traveling from city to city and imparting spiritual teachings, predictions of the future, and Persian poetry. In all his peregrinations, Abhai Chand remained his lifelong companion.

In the south Indian city of Hyderabad, Sarmad encountered the author of one of the earliest encyclopedias of world religion, the Dabistan, who was thrilled to meet a Jew in the flesh. He interviewed Sarmad on Jewish beliefs and customs, even if the ensuing account seems a bit unorthodox:

Sarmed gave the information that, according to the Yahuds, God, the Almighty, is corporeal; and that his body is after the image of mankind, and similar to it; that, during the course of time, he is dispersed in the same manner as splendor is dissipated. Sarmad moreover said, that it is mentioned in the Mosaic book and in the holy writings, that the spirit of the divine body is beauty itself, and manifests itself under a human form (translated from the Persian by David Shea and Anthony Troyer).

The author of the Dabistan notes that Sarmad and Abhai Chand translated at least part of the Torah into Persian. At the height of his renown and interfaith dealings, Sarmad was an active participant at the Mughal court in Delhi, where he interacted with European Jesuits, Hindus, and Muslim scholars alike. A close confidante of the “syncretizing” prince Dara Shikoh, he was also a vociferous critic of Dara’s brother and successor Aurangzeb. Likely as a result of his role in the political intrigue between brothers, Sarmad was executed on charges of public nudity or blasphemy in 1661 or 1662. To this day, he is venerated as a Sufi martyr and a Sufi “Jewish saint” of India, and his tomb in Delhi remains a place of pilgrimage.

Returning to the image of the genizah, the synagogue storeroom, what comes down to us through history is often arbitrary. Indeed, I discovered my current research topic by stumbling across an article in a Belgian theological journal, written by a Christian theologian with no formal Persian training.

At its core, a genizah was intended as a protection for the sacred, a repository for texts containing the name of God, which Jewish tradition deems too holy to be thrown away. Over time, however, genizahs came to include a mixture of the sacred, the profane, and the mundane. In the same way, we inherit fragments of the past, which point to complex lives such as that of the multifaceted “Jewish saint of India.”

Sasha Prevost, the 2015-16 I. Mervin and Georgiana Gorasht Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, is a second-year student jointly in Comparative Religion and the MA/PhD program in Asian Languages and Literature. She is a returnee to UW, having earned her BA in History and Comparative Religion with Honors in 2009. She also holds a Masters of Divinity from Harvard, where she concentrated in religion and gender and interfaith work. Her current research focuses on questions of conversion, religious hybridity, and the boundaries of religious identity, particularly in South Asia and the Persianate world. She is also interested in underexplored areas of Jewish identity. For the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship, she is researching the 17th- century Persian poet Sarmad Kashani, known as the “Jewish saint of India” or “Jewish-Yogi-Sufi Courtier of the Mughals,” and theorizing what pre-modern religious border-crossing can tell us about religious identity.

Sasha Prevost, the 2015-16 I. Mervin and Georgiana Gorasht Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, is a second-year student jointly in Comparative Religion and the MA/PhD program in Asian Languages and Literature. She is a returnee to UW, having earned her BA in History and Comparative Religion with Honors in 2009. She also holds a Masters of Divinity from Harvard, where she concentrated in religion and gender and interfaith work. Her current research focuses on questions of conversion, religious hybridity, and the boundaries of religious identity, particularly in South Asia and the Persianate world. She is also interested in underexplored areas of Jewish identity. For the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship, she is researching the 17th- century Persian poet Sarmad Kashani, known as the “Jewish saint of India” or “Jewish-Yogi-Sufi Courtier of the Mughals,” and theorizing what pre-modern religious border-crossing can tell us about religious identity.

Links for Further Exploration

- Graduate Fellows Spring Research Symposium, taking place May 6th, 2016

The unexpected intersections of faith identities still need to be brought to light. Reading this, again I remembered how interesting humans are. Sometimes it seems like we’re all fit to certain molds or categories. These constraints are mostly imaginary I suppose.

This is an excellent article speaking to the fluidity of identities prior to European colonization and racial/national identities as it relates to the Jewish community. This is an exciting topic and I look forward to seeing more work from you!

Jew, a Muslim, a Hindu, a non believer, a believer, a Sufi, a sinner, a sain and also all but non on these.

to understand Sarmad one must revolt, to come face to face with the tyrant and shout at its face..

Such is Sarmad’s charisma, he embraces humanity and all are forced to call him one of them..he is Sarmad Kashani, Sarmad Irani, Sarmad Sindhi, Sarmad Lahori, Sarmad Yahudi..call him by any name he shines on anyone who seeks him..

Sarmad must not be branded, he is mine too and I am not a Jew..