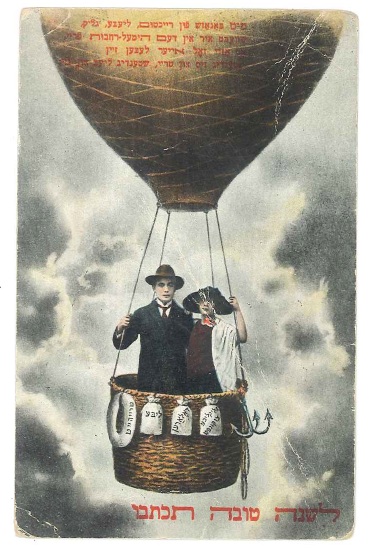

This Yiddish postcard was produced in Poland and ended up in South Africa. Courtesy of the private collection of Peta Karabus Mehlman.

These days, if you’re in the mood to send a greeting card for the Jewish New Year, you can buy a neatly wrapped stack of ten cards at just about any area grocery store, or browse dozens of websites to create a virtual greeting card. You could likely choose among a few familiar motifs: apples next to a bowl of glistening honey or perhaps a beehive; Jewish symbols like the Star of David or a Torah scroll; or maybe a shofar (ram’s horn), raised and ready to sound to the heavens.

What if we go a hundred years back in time? What options did Jews have if they wanted to send High Holiday greetings across the country–or across the globe?

It turns out, they had a plenty of choices, thanks to a flourishing industry of illustrated notecards that arose in Europe in the late 19th century. According to an article in the YIVO Encyclopedia by Jewish art expert Shalom Sabar, this industry took hold in Germany in the 1880s, spread to Poland, and eventually came to America in the early 20th century. The images on the cards ranged from biblical scenes to everyday shtetl life and Zionism; there were even non-Jewish companies that participated in the popular postcard industry.

Sabar notes that graphic artists like Khayim Goldberg would take photographs of actors performing Jewish rites in “traditional garb,” then add Yiddish rhymes to explain what was going on. These staged tableaux are actually revealing documents of Jewish life a century ago. Sabar explains, “Though reflecting artificial scenes, these postcards, which were published by Jehudia, contained invaluable ethnographic information about Jewish practices, costumes, and ritual objects, especially pertaining to the High Holidays and the Sabbath.”

The Yiddish Rosh Hashana postcard posted here came to my attention a few months ago, and I have been captivated by it ever since. My friend Peta Karabus Mehlman, who has several of these cards from the collection of her father, Morris Karabus, requested my help decoding the Yiddish handwriting on the back, so that she could understand another piece of her family’s history. Mehlman’s grandparents emigrated from Abel, Lithuania, to South Africa in the early 20th century (joining thousands of other Litvaks). Mehlman herself grew up in Beaufort West, South Africa, and also lived in Cape Town before immigrating to Canada. She lived in Toronto and Vancouver, then eventually moved to Seattle.

Mehlman says she is immensely curious about the couple on the postcard: “Who are these people? Are they family, and if they were, what were their stories, who are they related to besides our immediate family?” She sees deciphering the postcards as a way to possibly “connect the dots” and locate unknown relatives who might be out there. Given the practice Prof. Sabar described, wherein the postcard publishers would employ actors for their scenes, the true identity of this couple remains up in the air (to use an irresistible metaphor), yet the possibility of finding mishpokha (family) is indeed tantalizing. The back of the postcard bears the stamp of the Verlag Central publishing firm, which was based in Warsaw, so we know that this card originated in Poland — our first clue!

Let’s take a moment now to examine the front of the balloon postcard, as I’ve come to call it. It features a well-dressed young couple holding onto the ropes of a hot air balloon. Behind them are dark stormclouds — perhaps a reference to the political climate whenever this card was sent — but their balloon is suspended in a sunny clearing. The red text running along the bottom is a familiar New Year greeting: L’shana Tova Tikatevu, or “May you be inscribed for a good year,” a reference to the Book of Life, wherein, according to traditional Jewish belief, G-d will write the names of who will live and who will die in the coming year.

If we focus first on the set of Yiddish words aligned along the rim of the balloon’s basket, we can see the card’s theme of conveying good wishes for the new year. Three of the words are written on sandbags, which were dropped from a just-launched balloon to help it achieve liftoff. (I have no practical experience in hot air ballooning, so I thank the internet for this valuable information.) From right to left, the sandbags read: Gliklikhe tsukunft (A fortunate future); Dolaren (dollars); and Libeh (love). On the flotation ring on the left, the word Trayhayt (faithfulness or devotion) appears.

If we focus first on the set of Yiddish words aligned along the rim of the balloon’s basket, we can see the card’s theme of conveying good wishes for the new year. Three of the words are written on sandbags, which were dropped from a just-launched balloon to help it achieve liftoff. (I have no practical experience in hot air ballooning, so I thank the internet for this valuable information.) From right to left, the sandbags read: Gliklikhe tsukunft (A fortunate future); Dolaren (dollars); and Libeh (love). On the flotation ring on the left, the word Trayhayt (faithfulness or devotion) appears.

It’s especially interesting to me that the sandbag words are all items that one hopes the New Year will provide; and it strikes me as not a coincidence that trayhayt (devotion) is the word that’s written on the life ring. The implication (and it’s a very Jewish one) is that the quality of faithfulness — to one’s family, to one’s community, to one’s religion — will be the ultimate life preserver, the thing that ensures surviving and thriving even if the dolaren aren’t as copious as one would like.

What is the overall message of the balloon image combined with these positive words? One of aspiration, of hope, of soaring upwards into a prosperous year. The person receiving this card in South Africa would have felt heartened that, despite the stormclouds gathering in the skies, they might still glide into a happy future.

Today’s print and e-greeting cards for Rosh Hashana look rather different from this mysterious card produced in Poland decades ago, but the sentiment remains the same: at this hinge point of the Jewish calendar, as the old year turns into the new one, Jews want to reach out and send a message of hope, health, and prosperity to their loved ones around the world. Yet the picture is not complete without considering the Yiddish rhyme at the top of the card. Unpacking these verses, and the handwritten message written on the back of the card, will be the topic of my next post.

I am excited to launch this new series considering Yiddish, a language that is both incredibly heimish (home-y) and that also travels around the world, connecting dispersed Jews living in different lands. My thanks to Peta Karabus Mehlman for providing the first batch of intriguing materials that have inspired this exploration.

This is so cool. Great read!

So interesting! What a great article!

Thanks, Hannah, for such a great interpretation of this New Years card. It was very interesting!

Oh, awesome! So steampunk!!

Thanks Hannah,

I did receive a good Broad-Based Jewish Education — back on Long Island, N.Y.

The only time Yiddish was ever spoken — was so ‘the little ones’ would NOT know what their parents were saying. To me, unfortunate — communication between Parents and Children was never that important — at least in MY Family of Origin.

I am a third generation Austrian Jew.

“Unpacking these verses, and the handwritten message written on the back of the card, will be the topic of my next post.”

How can I follow so that I can read the next post?

Hi Adele, thanks for your interest! Hannah Pressman wrote this article a number of years ago. It looks like she didn’t end up writing another article about this postcard, but she did write a few more pieces about Yiddish in contemporary culture.