The Hebrew sign for the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem, Israel. Photo via Wikimedia.

In my undergraduate course on modern Hebrew literature, I often teach a short story published in 1955 and called, in English, “The Name.” The narrative is rather straightforward and revolves around selecting a name for an unborn child. Still, the story requires a great deal of context to understand. The first difficulty in teaching this text is the story’s title, its own name. In Hebrew the title is “Yad VaShem” [יד ושם], which is the Hebrew name of the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes Remembrance Authority. This institution was established by Israeli governmental charter in 1953, and its mission is to document, preserve, and educate about the Holocaust. The Hebrew name of the institution—and of the story—is derived from (Isaiah 56:5): “In My house and within My walls I will give them a place of honor and a name [יד ושם], which is better than sons and daughters; eternal renown will I give them, which will never be terminated.” Isaiah’s promise that those who uphold God’s commandments will have their memories endure thus frames Yad VaShem the institution as well as Aharon Megged’s story.

“The Name” focuses on a young Israeli couple who are having a baby and locked in a confrontation with the new mother’s grandfather, a more traditional Jew who by luck and a bit of prescience left before the Shoah. Presumably the action occurs contemporary to the story’s composition, a time characterized by socialist (Labor) Zionist conformity among a largely homogenous Jewish population that had only recently won its independence from the British and repelled invasion by a number of Arab states. This was also a time during which the mythos of the “New Hebrew”—the Hebrew-speaking, physically strong, self-sacrificing, productive laborer—was contrasted to the European Diaspora Jew, who was thought to be bookish, unproductive, weak-bodied, and who held bankrupt fantasies about Jewish enfranchisement or messianic promise.

Despite these negative stereotypes of Diaspora Jewry, the Shoah was certainly a trauma to Israeli society, not least because it exposed the underlying impotence of the Jewish community under the British Mandate in Palestine, and the Zionist project’s own vulnerability. The catastrophe of European Jewry also confirmed for many the superiority of the nascent state’s “New Hebrew” mythos, Israel’s justification for existence, and the prophetic nature of Zionism.

Got all that? Good, because my students need to know all this just to make sense of the central conflict in the story, which concerns what the young couple will name their unborn child. The aged grandfather wants to name the child after a beloved grandson who had been murdered by the Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators. The name of that boy was Mendele, a Yiddish name in its affectionate, diminutive form. The couple refuse to name their child Mendele, which the granddaughter calls “a Ghetto name, ugly, horrible.” They want a Hebrew name for their son, like “Ehud,” which conjures up the socio-historical background of the widespread Israeli custom of reinventing or rediscovering Hebrew names to replace those names that have an old world mustiness about them.

This family disagreement over a baby’s name reflects the wider struggle for remembrance going on in Israel at the time. A young Israeli man rejects the Jewish past with a sweeping “we have no ties to it”; an old man sees the younger generation’s lack of interest in the past to be “finishing off the work which the enemies of Israel began.” All this history of Israeli society at the time, and all this struggle with collective memory between these representative characters is contained in the struggle over this one name: Mendele. There’s nothing groundbreaking about this reading—just the standard interpretation. And yet, you can see the amount of context necessary just to understand the title, the central conflict, and the text’s linguistic codes.

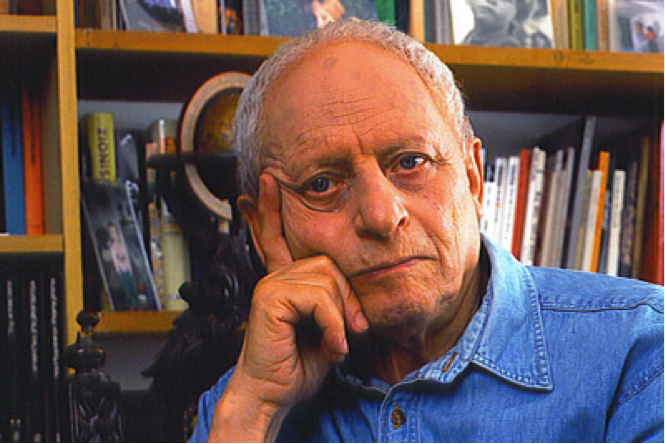

The author Aharon Megged, who immigrated to Israel from Poland at age 6. He passed away in March 2016.

Megged’s story, written a few years after the Holocaust, dramatizes the struggle for memory between those who have a surfeit of it (the Grandfather and his generation), and those who seek to free themselves of its burdens (the young Israeli couple and their generation). There is something of a paradox that a story that focuses to an extraordinary degree on the claims of history and memory is so obstinately hermetic for those—my American students—not already in possession of that history and memory.

So what to do in a class in which many of the readers are “students of circumstance”—fulfilling a requirement or patching a hole in their schedule? I think that for those of us who teach, rather than moan about a lack of undergraduate preparation, should acknowledge the reality and think about our role as translators of our knowledge and awareness of a culture for these students.

In some ways, these students of circumstance are my ideal students precisely because they are not the “ideal readers” of the text. They allow me, if I’m doing my job, to supplement the author and the translator in order to convey cultural context, history, memory. If literature mediates memory, translation naturally does so as well, but translating cultural memory is mostly what is not in a text; cultural memory is what remains beyond the text, around it, numinous yet somehow enmeshed within it. One tenet of teaching and of translating is—or maybe once was—the humanist notion that we can find the universal in the particular. After contextualizing the social history and the ideological era of the story’s composition, I have hopefully led my students to find within the story a greater richness.

Yet I’m always aware that in this story, as in many other Israeli stories, I have an undue amount of power to “name” the story for them, to give it provenance. Nonetheless, I think I’m justified in providing this provenance because, without context, the struggles with history Megged’s story describes are not transformed into memory for succeeding generations. And that, it seems to me, is the universal theme of Megged’s “Yad VaShem”: pass it on.

Adam Rovner is Associate Professor of English and Jewish Literature at the University of Denver. He is the author of In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands before Israel (NYU Press, 2014) and of essays on modern Jewish literature that have appeared in academic journals such as Partial Answers and AJS Review. He has served as Translations Editor for the magazine Zeek, handling the publication of Hebrew texts in English.

Adam Rovner is Associate Professor of English and Jewish Literature at the University of Denver. He is the author of In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands before Israel (NYU Press, 2014) and of essays on modern Jewish literature that have appeared in academic journals such as Partial Answers and AJS Review. He has served as Translations Editor for the magazine Zeek, handling the publication of Hebrew texts in English.

Leave A Comment