Prominent thinkers in the Haskalah (German Jewish Enlightenment) movement

By Yitzhak Melamed

The Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment movement) is commonly celebrated as the herald of modernity among the Jews. There is a considerable ideological bent in this perception—there were quite a few other Jewish modernities—but the Haskalah is indeed responsible for one of the most essential features of Jewish modernity: Protestantization. This point was captured quite early in Heinrich Heine’s Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland (1834-5):

Mendelssohn destroyed the authority of Talmudism and founded pure Mosaism… As Luther had overthrown the Papacy, so Mendelssohn overthrew the Talmud, and in the very same way, namely by repudiating tradition, by declaring the Bible to be the source of religion, and by translating the most important part of it. By so doing he destroyed Judaic Catholicism, as Luther has destroyed Christian Catholicism.

The German Jewish Enlightenment replaced the Talmud and its commentaries, the canonical texts of traditional Judaism, with the Bible. What was the reason for this sudden rise of a Jewish sola scriptura? A cynic may well argue that German Jews simply attempted to adopt the practices of their fellow Christian Burghers. My neighbor goes to the Kirche and studies the Bible, and so should I (though it would, of course, be a fine Judische Kirche!). It is also true that by the end of the eighteenth century very few among the Berlin Jewish bourgeoisie were able to decipher half a page of a rudimentary Talmudic text. Still, I believe that the deeper explanation lies elsewhere.

The dominant attitude toward traditional Judaism among the Berlin Maskilim (members of the Haskalah movement) was that of shame and embarrassment. Shame, of course, has an important role in the constitution of morality, and on many occasions may well be justified. But what was the crime or the immoral behavior that brought about this sense of shame in the Maskilim? Did the traditionalist Jews of Germany commit some horrible mass murder or some other moral horror? Perhaps, but I am not aware of any documentation of such an event. Perhaps this sense of shame was caused not by any immoral behavior, bur rather by the intellectual poverty of traditional Judaism?

Having studied some Talmudic and Rabbinic literature as well as Protestant theology, I have to confess that, in terms of analytic sophistication, these domains are incomparable. In terms of complexity and intellectual rigor, Rabbinic analysis is a few orders above Luther’s sermons and commentaries. What, then, was the reason for this sense of shame?

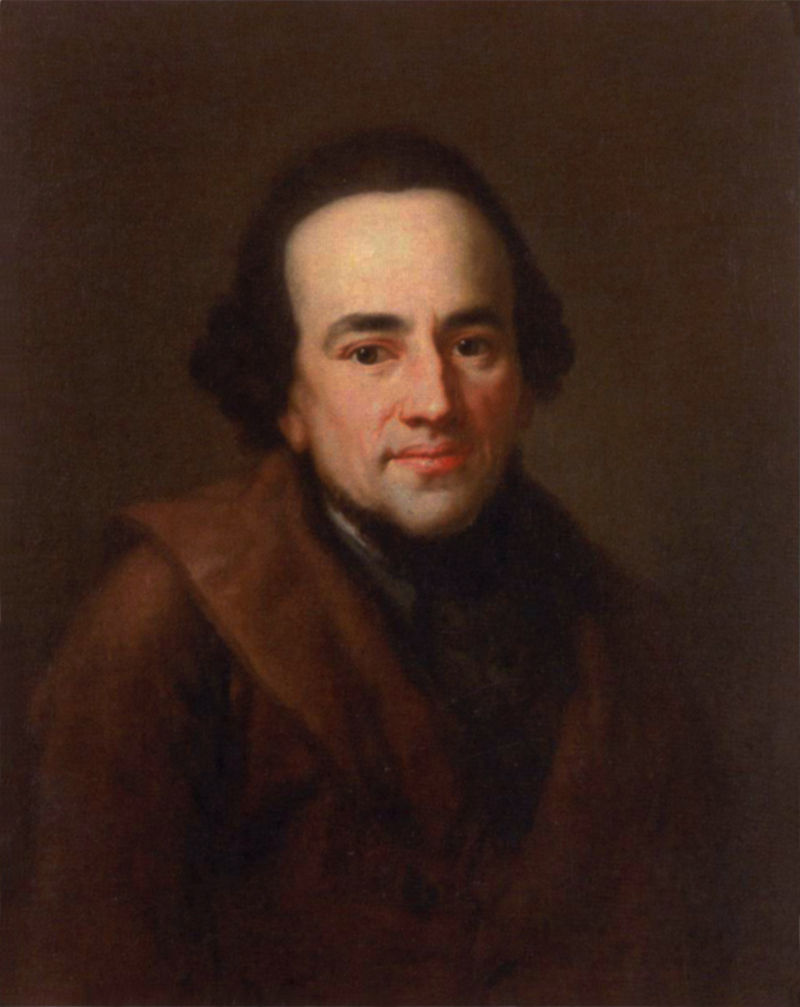

1771 portrait of philosopher and “Jewish Enlightenment” proponent Moses Mendelssohn, based on an original by Anton Graff. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In the absence of an alternative explanation, let me suggest that this sense of shame was due to an essential motive in the thought of the late Aufklärung (German Enlightenment): the hierarchy of “levels of acculturation” based on the distinction between those who do and do not have Bildung (the aptitude for self-cultivation). Indeed, Maskil philosopher Moses Mendelssohn speaks openly about the “levels of culture” of various nations; in notes drawn by Friedrich Nicolai following a conversation with Mendelssohn, the latter is quoted as suggesting that the Hebrew language was unfit for philosophy because of its oriental and uncultivated nature. (Let me note in passing that by 1781, the date of this conversation, Hebrew had a history of more than six centuries of philosophical writing, while German had hardly been used for philosophical writing before 1700.)

This hierarchy of cultures, which presented the traditional Jew as essentially inferior to the German/European, was immortalized sharply in the slogan of the nineteenth-century Haskalah: “Be a Jew in your tent, and a human being in the street.” The author of the saying, Yehuda Leib Gordon, seems to insinuate, unwittingly, that a Jew is not a human being, or at least not the paradigmatic human being. Being less cultivated than paradigmatic humanity, Jewishness was supposed to be restricted to the space of one’s tent (note well: tent, not house). Leaving the tent, the Jew must ascend to the rank of a human being–presumably, a white European, but clearly not a Jew.

Where should we locate Spinoza against this background of the Jewish Enlightenment and modernity? The Berlin Haskalah was not particularly fond of Spinoza. Spinoza was a radical, and the Berlin Maskilim were anything but radicals. Still, the Haskalah’s Biblicalism and Spinoza’s insistence that the Bible should be read literally might tempt one to view Spinoza as the precursor of the Jewish Enlightenment. Was Spinoza the Founding Father of modern Jewish Protestantism?

Spinoza was described by one of his contemporaries as a “Protestant Jew.” Yet a remarkable feature of Spinoza’s attitude to Judaism is the absence of any sense of shame. Was Spinoza free of the Haskalah’s sense of shame simply because he did not identify himself as a Jew, or was it instead Spinoza’s independence of mind that allowed him to be highly critical of several key aspects of traditional culture, while still presenting this culture as neither inferior nor superior to other cultures?

Yitzhak Y. Melamed is the Charlotte Bloomberg Professor of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University. He works on Early Modern Philosophy, German Idealism, Medieval Philosophy, and some issues in contemporary metaphysics (time, mereology, and trope theory), and is the author of Spinoza’s Metaphysics: Substance and Thought (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Yitzhak Y. Melamed is the Charlotte Bloomberg Professor of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University. He works on Early Modern Philosophy, German Idealism, Medieval Philosophy, and some issues in contemporary metaphysics (time, mereology, and trope theory), and is the author of Spinoza’s Metaphysics: Substance and Thought (Oxford University Press, 2013).

For Further Exploration

- How Did the Enlightenment Shape the Jews? by Jonathan Israel, April 2017

- Prophets at War: Hermann Cohen and German Jews in the First World War by Michael Rosenthal, January 2017

- Register for the Spring 2017 Stroum Lectures with Jonathan Israel

Leave A Comment