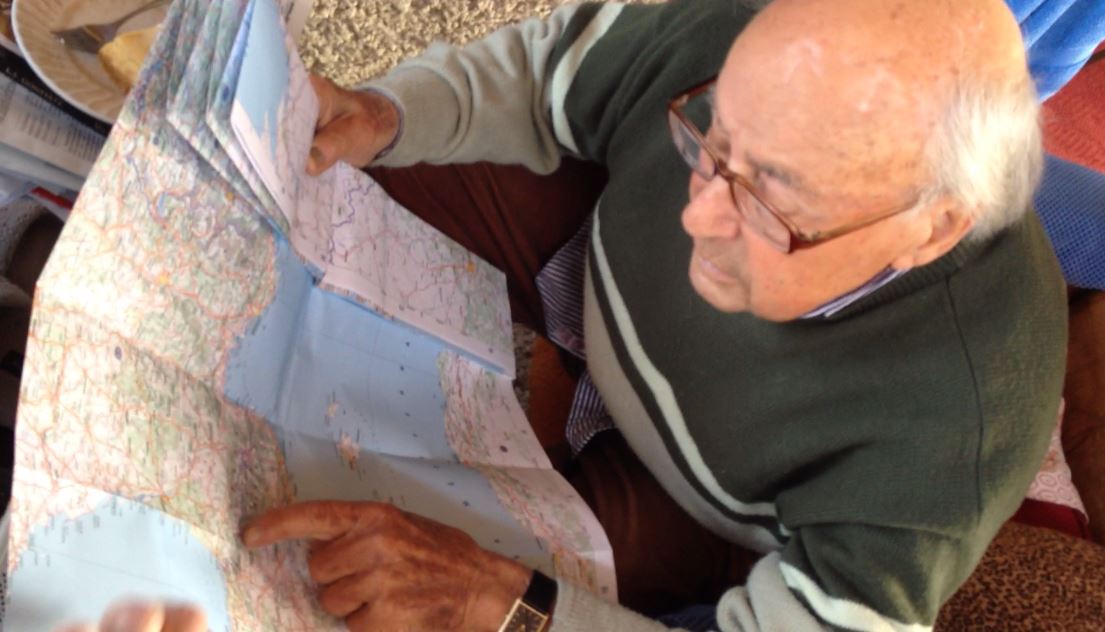

Werner Cahn retraces his path through Europe during a 2014 conversation with Ryan Gompertz, his great-nephew.

Every family has a story.

My Great-Great-Uncle Werner Cahn was born in Aachen, Germany in 1920. In 1948, he moved to San Diego, where he has lived ever since. In April of 2014, he and I sat in a sunny corner of his home. I brought with me a notepad, a map of Europe, and a ten dollar tripod for my iPhone. After unfolding the map on the table in front of us, I pressed “record” and asked him a simple question.

“Uncle Werner, how did you get here?”

This research project was born of that question. For the next three hours, Werner described living in Holland when Hitler’s tanks rolled across the border. He remembered working his way south under an assumed identity, meeting with resistance contacts along the way. He recalled crossing the Pyrenees on foot, he and his fellow refugees guided by smugglers to evade Nazi patrols and safely enter Spain. He reminisced about his time on a kibbutz in Israel.

Three hours and a full hard drive later, Werner reflected on his experience: “It’s insane. I was lucky. I was just lucky.”

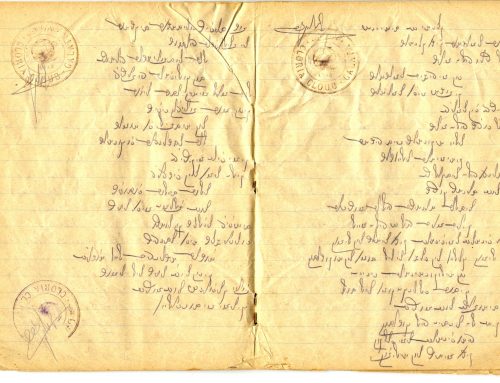

Werner’s experience is a powerful story of perseverance, courage, and miraculous luck. Though the exact details of his account are unique to him, the overarching themes exist across many stories in many families. Other Jewish refugees remember similar extraordinary journeys in their paths from certain danger to uncertain futures. Claude Vigée was a French doctor who produced fake autopsy reports to help detained refugees elude Vichy authorities. Lisa Fittko was a German anti-fascist who escaped across the Pyrenees only to turn back to help others do the same. Sam Levy was a relief worker who used his Portuguese citizenship and Red Cross connections to connect refugees with international organizations who could deliver them to safe destinations.

These stories are history in the flesh, accounts of the past to which we owe our present, and a chance to reconnect our identity to our heritage.

Every family has a story. Are they history? Many students are taught that historians must be removed from and impartial to their work. Thankfully, I was not. Professors in the Department of History and Stroum Center encouraged me to channel my enthusiasm and connection to the subject into strong research. In particular, Professors Glennys Young and Devin Naar were strong influences without whom my work would not have been possible. What began as personal turned historical thanks in large part to their guidance and input. I am most grateful for their conviction in highlighting the value of first-hand accounts, which elsewhere might have been disregarded as “biased” and “limited” in their historical value.

Ryan Gompertz at the UW History Department Convocation, June 2015.

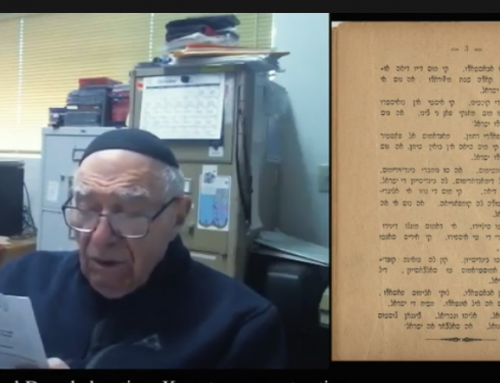

This summer, the UW Stroum Center for Jewish Studies has enabled me to take my research further. Through the Digital Media Fellowship Program, I received the support and resources I needed to make my work accessible. The “Mapping Memory” webpage represents an incomplete list of all those who came before, those to whom we may owe our lives, our identities, and our memories. It is my hope that placing these memories in a geographic context will amplify their power. It will put these stories into perspective, tracing the paths these individuals took onto an interactive map, allowing visitors to understand the distance and difficulty involved. Most importantly, it will give visitors insight not just into what these individuals did, but who they were before the war and who they were after. Thanks to the Stroum Center, “Mapping Memory” will be the meeting point for families’ stories and history.

After all, every family has a story. Be it one of heroism, compassion, of courage, or luck, these stories must be remembered. This digital project for the UW Stroum Center for Jewish Studies began as an effort to record my family’s story, but the search for similar first-hand accounts has expanded it into an effort to record others as well. These stories are history in the flesh, accounts of the past to which we owe our present, and a chance to reconnect our identity to our heritage.

Unfortunately, these stories are also fading. Werner was born in 1920, Levy in 1912, Vigée in 1921, and Fittko in 1909. With every year that passes, we grow more distant from these events, a fact that threatens to sever our connection through those who experienced them. It is my hope that those who visit this web page will reflect on the stories in their families and make an effort to preserve them. With a notebook, a map, and a ten-dollar tripod, we can add story by story to the map, filling in the spaces until the empty map is covered by crisscrossing histories.

Congratulations Ryan, a wonderful project.

I’m involved with a number of WW2 escape line commemorative organisations and am giving a presentation on escape lines at a Holocaust Memorial Day event later this month in London. I look forward to mentioning your project/website.

Regards

John