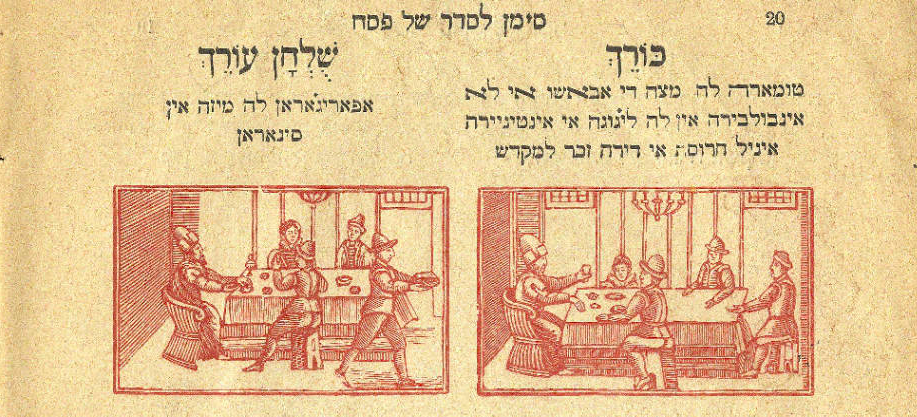

Closeup from a Ladino Haggadah published in Livorno, Italy ca. 1903-04, shows a mix of Hebrew and Ladino, as well as woodcut illustrations common to Italian Jewish texts. Courtesy of Susan Solomon and the Sephardic Studies Digital Library & Museum.

Every haggadah used at a Passover seder table has a few stories to tell. There is the Passover story, of course–the Jews’ enslavement in Egypt and eventual liberation, a narrative of redemption that resonates across time and cultures. Yet within the pages of the haggadah itself are other stories, too. Drops of wine or smudges of haroset (fruit-nut paste) on the pages are forensic clues to what was eaten and drunk at long-ago gatherings. Particular editions of the haggadah come attached with memories and emotions; you could open a haggadah and find, wedged inside, a folded copy of a text study your grandfather led several years ago, or the lyrics to a silly song about frogs your aunt wrote for the children in attendance.

The very look of a haggadah–how the Hebrew and Aramaic texts combine with pictures–play a role in our connections to the holiday. Who knew that the Maxwell House Haggadah, published continuously for upwards of a century, would become, in the words of the Forward’s Anne Cohen, “almost as emblematic of the holiday as the Seder plate and Elijah’s cup among Jews of the Diaspora”? The jury is still out if a similar iconic status will be reached by the design of the so-called “hipster Haggadah,” the appealing compilation created in 2012 by Jewish American novelists Jonathan Safran Foer and Nathan Englander.

A new acquisition by the Sephardic Studies Digital Library & Museum at the UW allows us into the world and rituals of Sephardic Jews at the turn of the twentieth century. Published in 1903 or 1904 in Livorno, Italy, by the Shelomo Belforte publishing house, this Passover haggadah has smudges, spills, and creases, evidence that it was well used and well loved. The haggadah was donated by Seattle resident Susan Solomon; it belonged to her grandmother Susan Angel (nee Azose), whose father was Haribi Yitzhak (Isaac) Azose. Azose is well known in Seattle’s Jewish history for serving as the second rabbi of Sephardic Bikur Holim synagogue from 1919-1924. According to her daughter Sylvia Angel, Susan Angel absorbed the Passover customs from her father the rabbi, and as an adult would lead the family seder for her seven children and assorted family members.

You can visit this link at the online museum to examine each scanned page of the Angel haggadah in high-resolution detail. A button bar appears along the top, offering a helpful zoom-in and zoom-out tool that lets you see the text and images in great detail. Viewers can also choose to see the item on their screen in “full browser” mode, “fit to window,” or “fit to width”; thumbnail images of every page appear arranged in order at the bottom of the screen or on the righthand side of the screen for easy clicking and skipping around in the text.

Exploring in the digital museum: Buttons at the top of the screen allow viewers to zoom on the page and choose what type of viewing mode.

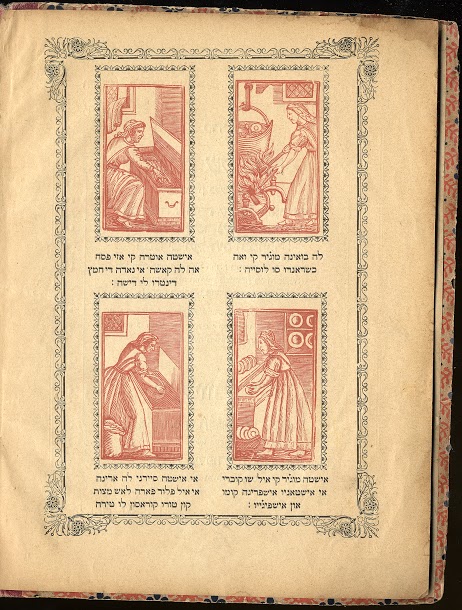

Thus, when paging through this special haggadah, you can find the inside cover inscribed with the name of Susan Angel, a reminder that she so often led her family’s seders. You can also zoom in on the fascinating woodcut illustrations, which are of a style typical to Italian Jewish religious texts and can be seen in other haggadot, such as this Venitian haggadah published in 1609. Interestingly, while it was published outside of the Ottoman Empire in Italy, this haggadah—a word which Sephardim pronounce as agadá, without the “h” sound on the front—was used by Ottoman-born Jews.

Also of note is the mixture of Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) with the “official” languages of the haggadah, Hebrew and Aramaic. For example, the image at the top of this article is taken from a section outlining the many steps of the seder (the word seder itself means “order,” and the meal has a detailed choreography involving a series of symbolic foods, blessings, and narratives). The headings naming the steps are written in Hebrew: on the right is Korekh, wherein seder participants eat the famous Hillel sandwich of matzoh and bitter herbs; and on the left is Shulhan Orekh, the holiday meal. However, the explanations underneath these Hebrew headings are written in Ladino for the easy comprehension of Sephardic audiences in the early twentieth century.

Woodcut illustrations from the Ladino Haggadah published in Livorno, Italy ca. 1903-04. Courtesy of Susan Solomon and the Sephardic Studies Digital Library & Museum.

Today, however, items like this Livorno Ladino haggadah are precious mementos from a bygone period of Sephardic Jewish language and culture. Since this haggadah appeared in 1903, migrations, persecution, and geopolitical shifts have radically changed the locations and makeup of the global Sephardic community. Yet at the same time, this haggadah reminds us of religious rituals that span time and place. The order of the seder remains the same, no matter where you are or what language you speak.

Ultimately, perhaps, each family creates a set of Passover resources and rituals unique to their own circumstances. Thinking about her mother’s haggadah, Sylvia Angel reflected on how her family ended up combining Turkish Jewish and American Jewish customs: “It was always a traditional Turkish Sephardic ceremony that we followed to a ‘t’ according to my mom’s family’s tradition. Not any of us ever had the same book, since our Hagaddot came from Turkey, so it was difficult to follow the service in an organized fashion. Not until the 1960’s when we bought two dozen Maxwell House Haggadot were we able to stay together

Whether your Passover memories are linked to Maxwell House coffee ads or Italian woodcuts; whether you’ll be singing “Who Knows One?” in Hebrew, Ladino, Yiddish, Aramaic, Arabic, or English; whether you pronounce it matzoh or masá; and whether you’ll be following each seder step or making your own post-modern ritual mashup—for all who celebrate, may this be a Pesah alegre (Ladino for “a happy Passover”), a zissen Pesach (Yiddish for “a sweet Passover”), and a time for adding new stories to the mix.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

I have a copy of the Haggadah you show that I bought some 40 years ago in Marseille (France) and I still speak ladino as I was born in Tangier (Morocco).

I am interested in buying an other sample of this Haggadah, do you know where I can find it?

If I can help in any way as I still speak and understand haketia that is the judeo-spanish language my grand mother talked and is similar to ladino?

Thanks,

Ephraim Medina

Hi, Is there free online a Ladino Haggadah? Let me know where please to find one in Latin/Spanish, English/French,etc alphabet.

Hi, we have several haggadot in Ladino in our Sephardic Digital Library. Here is the link to the haggadot. You might also be interested in the Digital Library index, and some more information about the Digital Library project.