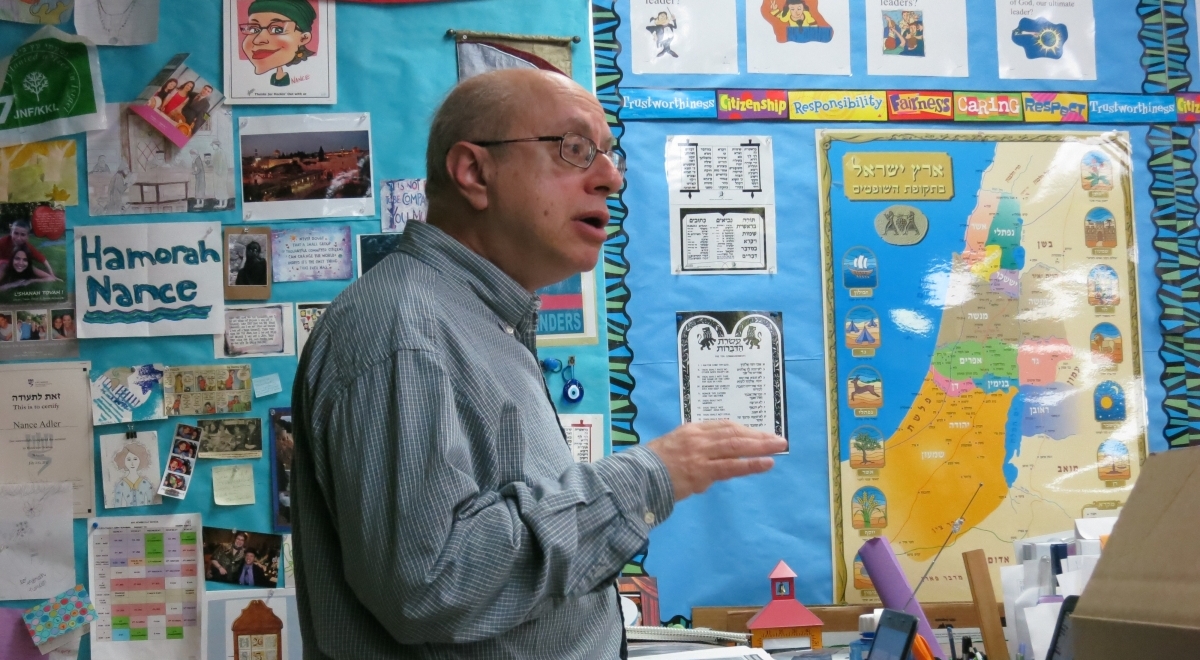

Prof. David Bunis spoke about Ladino and Jewish languages at a visit to the Jewish Day School in Bellevue.

You know you have a successful academic program when a student learns a language they didn’t know existed.

That’s exactly what happened when Hebrew University’s Prof. David Bunis spent a year at the University of Washington teaching Ladino.

“I didn’t even know what Ladino was before taking this class,” one student remarked in a course evaluation.

Prof. Bunis is the head of the Ladino Studies Program at Hebrew University’s Center for Jewish Languages and Literatures. He was the guest of the Jackson School of International Studies and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies during the 2013-14 academic year. Prof. Bunis has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Yad Ben Zvi’s Life’s Work Prize in 2006 and the EMET Prize for the Study of Jewish Languages in 2013. As the Schusterman Visiting Israeli Professor of Israel Studies and in co-sponsorship with the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise and the SamIS Foundation, this prestigious scholar offered the only undergraduate class at an American university where students could learn the Ladino language in the traditional Hebrew scripts.

As the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies celebrated its 40th anniversary at the UW, it was especially fitting to have an outstanding scholar like Bunis here.

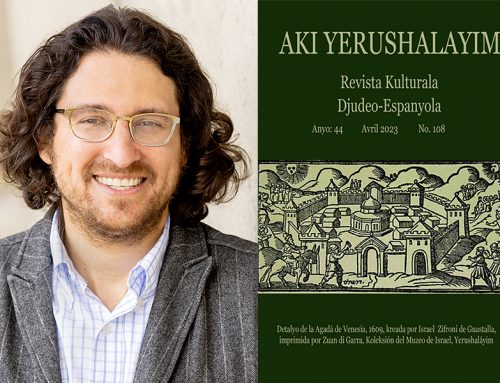

“We now have an unprecedented cohort of more than two dozen undergrad students — Jewish and non-Jewish, from Spanish majors to computer science majors — who are literate in Ladino,” said Sephardic Studies Program Chair Devin Naar. “Ultimately, we’d like to transform Ladino into a permanent feature of our Sephardic Studies curriculum in partnership with Jewish Studies and the Division of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, whether as regular academic courses or intensive summer sessions (or both!).”

Bunis’ own interest in the language began as a teenager, after visiting a synagogue in Brighton Beach, New York, where many of the members spoke Ladino. It was here that he first began recording Ladino speakers and studying literature, songs and speech patterns that would earn him a scholarship in Jewish languages. Bunis fondly remembers studying Ladino from a 1920s booklet for Salonikan children sent to him by a woman in Jerusalem.

“From the booklet I, too, began to learn to read Ladino in Rashí—and to make my way toward a lifelong career in Ladino studies,” he said.

Bunis began the year with a standing-room-only lecture, “Ladino/Judezmo as a Jewish Language,” where he presented the rapt audience with his historiography of Ladino, also known as Judeo-Espanyol or Judezmo. (Bunis prefers these latter terms to Ladino. The term Judezmo, for example, emphasizes the fundamentally “Jewish” nature of the language.)

In addition to two courses on the language — “Ladino for Beginners” and “History of the Ladino Language and Literature” — Bunis also taught a course entitled “Language and Ethnicity in Israel Today” and “Sephardim in Jerusalem,” a fascinating class that combined numerous languages and a wide range of texts to portray how the holy city was viewed in the Sephardic mind.

The courses, which reached maximum enrollment, attracted university students from myriad backgrounds and disciplines as well as community members.

“I never thought I would have an opportunity to study under an expert of the Ladino language outside of Israel,” said Sarah Zaides, a doctoral candidate in history and former Jewish Studies Graduate Fellow. “I believed learning Ladino meant studying with a textbook — not with a world-class linguist in the library at the UW in Seattle.”

Several students reflected that the courses fomented a sort of Ladino revival in Seattle, and for others Bunis brought them closer to their personal narratives.

“The class validated my identity as a Sephardic Jew and its uniqueness,” said Marlene Souriano-Vinikor, a non-matriculated student.

Not only did he teach students how to read and write in Rashi characters, but Bunis also encouraged students to type in this script. Not only was he was able to point to the biblical origins of a Ladino word, but he could also explain its use in the popular vernacular of Izmir at the turn of the century.

Another highlight of these courses were frequent visits by guest lecturers, including Dr. Eliezer Papo, Director of the Sephardic Studies Institute at Ben Gurion University in the Negev and a rabbi, who shared everything from Ladino “blue” humor to medieval Passover proverbs. A number of presentations came from first-generation Americans who grew up in Ladino-speaking homes, like Al Shemareya, who shared handwritten Ladino documents including his mother’s potato boreka recipe and a postcard of his family’s former house on the island of Rhodes, for which they received Holocaust reparations.

“I felt very honored when

“I actually had made contact with Prof. Bunis in the 1970s sometime, when he was running a little organization called The Judezmo Society and publishing a one- or two-page newsletter with the title ‘Ke Xaber’ (What’s New?),” Azose said. “I was very happy when I heard that he was coming to the UW to teach for a year. I had always wanted to get to know him a little better…. He has been very helpful in our weekly Tuesday Ladino class, especially with the meanings of many Turkish words.”

Bunis also gave several presentations around Seattle at area synagogues, schools, and the Seattle Jewish Film Festival. On a snowy day, when everything in Seattle threatened to close down, Bunis braved the wintry weather to join a panel with Prof. Naar, Prof. Zvi Zohar from Bar Ilan University, and Rabbi Daniel Bouskila from the Sephardic Education Center in Los Angeles at the Majestic Bay Theatres after a screening of “The Visionary: The Life of Rabbi Ben Zion Meir Hai Uziel.” In downtown Seattle, following the Seattle Jewish Film Festival’s screening of the “The Longest Journey: The Last Days of the Jews of Rhodes,” Bunis participated in the very emotional panel discussion, “Ladino: Past, Present & Future” with Naar, Eliezer Papo, and Turkish scholar Karen Gerson Şarhon.

For me, in my first year as the research coordinator of the Sephardic Studies Program and completely consumed with over 100,000 pages of Ladino materials in the Sephardic Studies Digital Library , Bunis’ presence on and off campus was immeasurable. I tried to restrain myself every time I ran into him, both at the Turkish Sephardic Bikur Holim and at Ezra Bessaroth synagogue where he was attempting to enjoy the Ladino liturgy, which still follows the customs of Rhodes. I cornered him by the copier to have him help me translate a printer’s note I was unsure about. “I am on my way to speak with a Turkish expert,” he answered, “I am sure that she will be able to translate and explain the Turkish script printed on the title page.” Which he immediately did and which turned out to be great help for future research.

Although Bunis has returned to Jerusalem, he is still with us as part of the academic advisory committee for the Sephardic Treasures Archive and Museum, along with Aron Rodrigue of Stanford University, Julia Phillips Cohen of Vanderbilt University, Sarah Abrevaya Stein of UCLA, Eliezer Papo of Ben Gurion University in the Negev, and Karen Gerson Sarhon, director of the Ottoman Turkish Sephardic Research Center in Istanbul.

“It was an especial pleasure to interact this year with the students at UW,” Bunis told me. “I found them to be highly motivated, and genuinely interested in and excited by the Ladino texts we read and analyzed in class…. The students’ enthusiasm for the subject was infectious: I looked forward to leading every session, and I think it brought out the best in the visitors and members of the class from the Sephardic community who graciously shared their personal experiences with the group.”

“He is by far the best teacher I have learned any subject from!” exclaimed Sylvia Angel, an active member of the community. “And coming from a 70-year-old, that speaks volumes.” Angel went on to thank Noam Pianko, Director of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies; Devin Naar; and the program’s donors for putting UW Sephardic Studies on the map.

“We are indeed blessed to have so many fine professors, interesting classes and thoughtful leaders in this city,” she said. “We have a real treasure in our community, and we have so much to be thankful for.”

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Ty: Great writing! And, many thanks for including my notes about the great professors, interesting programs and fantastic classes offered through our unique Jewish & Sephardic Studies Programs. We truly are blessed to have so many fine choices and offerings for our community members.