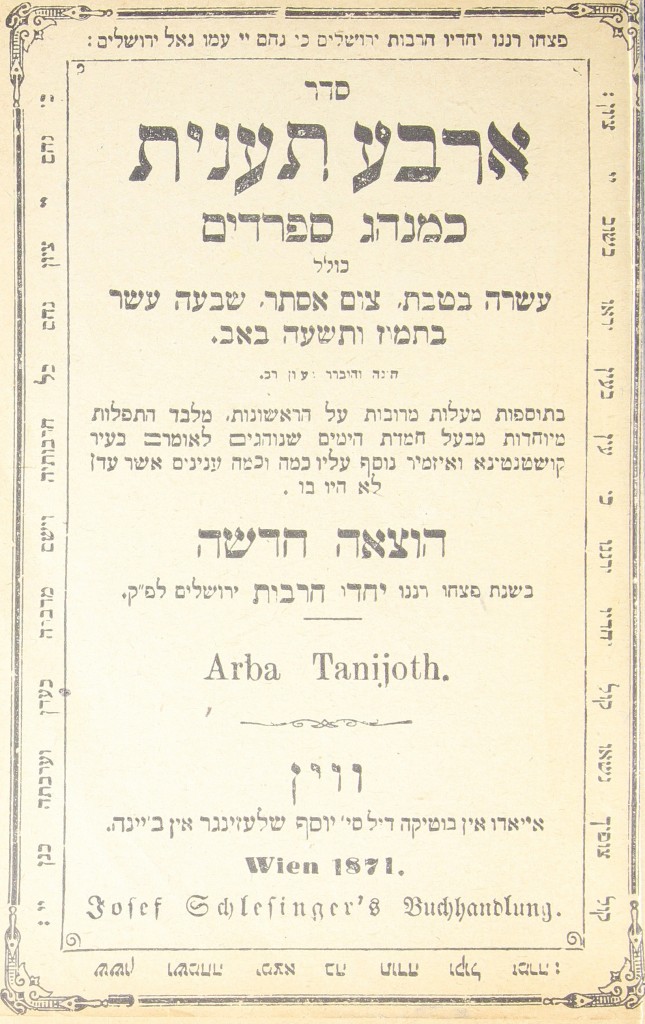

Title page of the 1871 version of “Arba Ta’aniot.”

Ticha be’ave mos asentamos en bacho atomar tanid. La mama se veste de preto por honor de loz djidios Ke foueron masakrados a esta dato…

On Tisha B’Av, we sit on the floor and fast. Mother wears black in honor of the Jews Who were massacred on this date…

~ A reflection on Tisha Be-Av by Bouena Sarfatty, from Salonica, as published in Renee Levine Melammed, An Ode to Salonika (Indiana University Press, 2013), p. 143

Across the globe, the Jewish people have gathered for two millennia to read the harrowing words of the prophet Jeremiah on the 9th day of the Hebrew month of Av. “I will scatter them among the nations, that neither they nor their fathers have known,” the prophet warns, “and I will send the sword after them, until I have annihilated them.”

As Bouena Sarfatty’s reflection evokes, Tisha Be-Av is a holiday that commemorates a day of great calamity on the Jewish calendar. Mourning the Babylonian destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE and the Roman destruction in 68 CE, Tisha Be-Av has become synonymous with the scattering of the Jewish population across the globe. For Sephardic Jews, the 9th of Av is also the infamous date attributed to the expulsion from Spain in 1492. In Seattle, it is also tragically associated with the German deportation of the Jews of Rhodes who spent their final Tisha Be-Av onboard small cargo boats headed to the Haidari concentration camp in Athens from which they were sent to their deaths at Auschwitz.

The severity of this day has always been on the tongues of the Sephardic Jews as evidenced by common folk sayings in Ladino, some of which Rebecca Amato Levy recorded in her memoir, I Remember Rhodes (pp. 103-113): Este es Yermia el profeta (so-and-so cries like the prophet Jeremiah). Ke darshe mi iju ke sea en dia de Tisha B’Av (let my son prove himself, even on the day of Tisha Be-Av). When someone was impatient and felt that something was taking too long they might say, Esta arastado komo la aftara de Tisha Be-Av (dragging on like the haftarah of Tisha Be-Av), a sarcastic reference to the lengthy Ladino translation of Jeremiah read in the Sephardic liturgy.

The entire Sephardic liturgy for Tisha Be-Av, including the Ladino translation of Jeremiah, is now available online at the UW’s Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, which contains two editions of Seder Arba Ta’aniot: ke minhag Sefaradim (The Four Fasts: According to Customs of the Sephardim [the other three fasts included are the 10th of Ṭevet, The Fast of Esther, The 17th of Tammuz). Click here to see the 1921 edition; and the 1871 edition is also available for viewing by clicking here.

Remarkably, the 1871 edition is one of only three known copies in the world according to the international library catalog, Worldcat. Both editions of Seder Arba Ta’aniot contain Hebrew with the Ladino texts printed in Rashi characters and were published by the famous printing house of Joseph Schlesinger in Vienna, whose books catered to the Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire. The two editions of Seder Arba Ta’aniot tell us not only about Tisha Be-Av traditions, but also reveal the stories of the books’ owners and their communities that transport us from the “Old World” to the Puget Sound.

These two editions of Seder Arba Ta’aniot were made available to the Sephardic Studies Program courtesy of Elazar Behar, a longtime leader of Seattle’s Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, who has generously shared over 45 Ladino books with us, including both religious and secular texts. According to Mr. Behar, he received these two editions of Seder Arba Ta’aniot from his late father, the Rev. David J. Behar, who served as the hazzan (cantor) and Haham (spiritual leader) of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth from 1918 to 1966.

Haham David ben Ya’akov Behar was born in 1894, in Beirut, Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire. As a boy, he accompanied his father and brothers as they traveled throughout the sultan’s realm, on foot, and with mules by their side, as they sold coffee and visited Jewish communities along the way. Later, with his wife “Buena” Lea (née Sharhon), Haham Behar raised eleven children with whom he shared his books, traditions and memories.

“One of his vivid memories, that he used to enjoy telling us is that, when they crossed into Israel on these camel caravans and after being in the hot desert, they would look forward to getting to the Dead Sea,” Elazar described in an oral history recorded by the Washington State Jewish Historical Society in 1982. “They would soak their feet and get rid of their blisters. It had healing qualities. It was always a big treat to get over to the Dead Sea with the caravan and relax and get refreshed and healed.”

Elazar described his own childhood, during the depression, as being split between playing with his friends in Seattle’s “old neighborhood” (the Central District) and loyally following his father to religious services and life cycle events among the new Sephardic immigrants. “Ever since I was about age three, I was almost like an adjunct to my dad. I was almost attached to him. I went everywhere with him.” He describes how they would walk up and down Yesler Way, attending to the community’s political, spiritual and personal needs.

Haham David Behar preparing bags containing worn out prayer books and other unusable holy objects for burial, Seattle, ca. 1932. Courtesy of the UW Digital Library.

They would go to the homes of Sephardic women, like my own great-grandmother “Behora” Rebecca Alhadeff, to help them learn English for their American citizenship tests. Elazar followed his father to meet with many local business leaders and rabbis from all of the denominations. The only exception was when his father would go alone to visit the deathbeds of the sick and elderly. “If somebody was sick, the Haham was at the hospital,” Elazar recalled. “He knew when they were dying, I don’t know how, but he knew.”

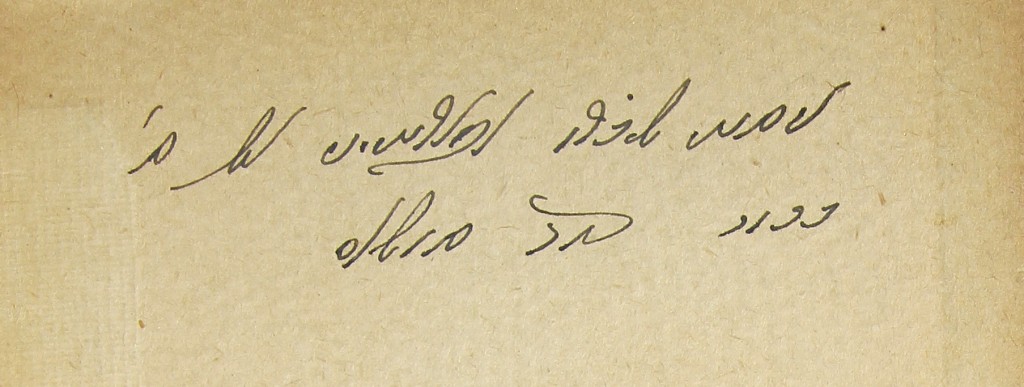

Haham Behar’s role as a leader who participated in all the lifecycle events among Seattle’s Sephardic Jews transformed his personal bookshelves into a communal library. It is not surprising that the extremely rare 1871 edition of Seder Arba Ta’aniot had belonged to someone else before it entered the Behar library. A handwritten Ladino inscription in Soletreo on the inside front cover of this book reads: Este livro apartiene al s[enyor] Behor David Solam (“This book belongs to Mr. Behor David Solam.”)

The Soletreo inscription from Behor David Solam’s copy of “Arba Taaniot,” 1871.

According to his draft registration card and US census data, the late Mr. Solam was a native of Leros, a Dodecanese island near Rhodes. In 1911, he immigrated to Seattle, where he raised a family and worked as a driver for Lippman’s Bakery on 23rd Avenue between Yesler and Fir, and, later, as a salesman. Active in the Sephardic community, Solam served as a gabbai (beadle) at Ezra Bessaroth and played an integral role in assisting Haham Behar with the purchase of the Sephardic Brotherhood Cemetery in Seattle in 1933. As Haham Behar’s son, Elazar, succeeded Solam as a gabbai of Ezra Bessaroth, it seems fitting that he should inherit this edition of Seder Arba Ta’aniot.

Just like the people themselves, the books and traditions of Seattle’s Sephardic Jews traveled from the old world to the new, and from one generation to the next. Many of Haham Behar’s children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren continue their family’s key roles as gabbais (beadles), hazzanim (cantors) and leaders of Ezra Bessaroth.

Adding a new chapter to the story, the cantor emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, Isaac Azose, recently codified the Seattle Sephardic liturgy for the fast days, including Tisha Be-Av, in his Tefilah Le-Moshe: Seder Hamesh Ta’aniot (Order of the Five Fast Days). Mr. Azose explains that he based his prayer book on none other than Seder Arba Ta’aniot published in Vienna (an 1877 edition). In so doing, Mr. Azose preserves the linkages from Vienna and the Ottoman Empire to the Puget Sound for the twenty-first century. Mr. Azose’s 2012 edition contains a new innovation: the Ladino liturgy not in traditional rashi script, but rather in Latin-lettered transliteration in order to make it more accessible to readers today.

The Sephardic Studies Program at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies is excited to share many more texts from the libraries of Elazar Behar and other members of the Seattle Sephardic community that shed new light not only on the literary and religious traditions of the Sephardic Jews, but also provide us with an entry point into the worlds and the stories of those who owned the books and transported them from the old world to the new. It is our pleasure to make these texts available online, in digital format for the first time, so that all those interested, wherever they reside in the world, may be able to access them for generations to come.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading this, and that no esta arrastando komo la aftara de Tisha Be-Av (it hasn’t dragged on longer than the haftarah of Tisha Be-Av)!

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Ty: I am so proud of you for writing such a fine and interesting article about our past Sephardic history in Seattle, where, as you know, I was born and raised. I knew and loved Rev. Behar, like a papoo, and I know he loved me too. Sadly, I didn’t know either of my papoos. My father Avner, was one of his right hand men, who admired and and respected him greatly. Rev. Behar was a very kind, gentle and sweet man who was a true leader in our kehila. I will never forget his kindness and his warmth towards our family; he was a true blessing to our community.

Ty, please keep up your excellent writing skills. I so admire all the great things you are doing in our community. I am so proud of all you have accomplished in your job with the Sephardic Studies Dept at the UW. May you go from strength to strength. Kon muncho karensia, Silvyika