Associate membership: more inclusive than you realize

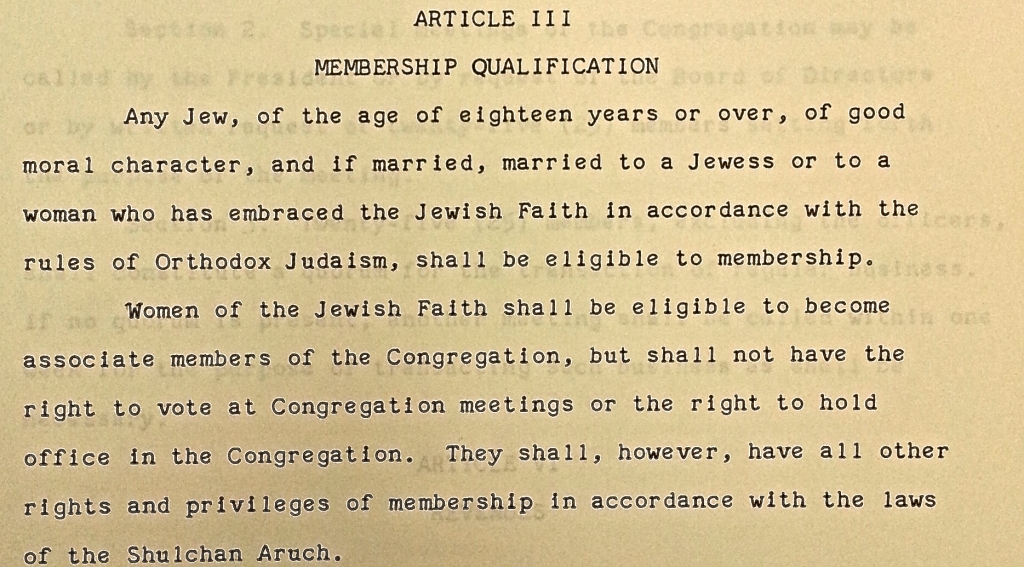

The above passage is from the first published constitution of Bikur Cholim Machzikay Hadath dating back to 1921. At this point in history the suffrage fight was just winding down. Washington State had granted suffrage rights to women 11 years earlier in 1910, and the 19th amendment that federally prohibited voting restrictions based on sex was passed the year before this publication in 1920. While to our modern view this constitution seems to discriminate against women, for its time period, and within Orthodox Judaism this excerpt is extremely permissive. Traditional Orthodox synagogues at the time could have easily resisted change, stubbornly denying women any explicit “constitutional” rights. Instead, the Congregation grants associate membership to women. What could have influenced this institution to allow women members?

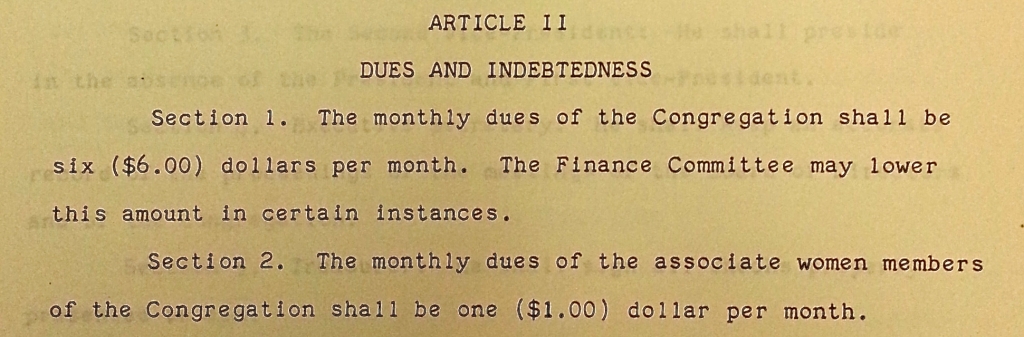

The first line of our excerpt above provides a clue. It reads, “if married, married to a Jewess or a woman who has embraced the Jewish faith in accordance with the rules of the Orthodox Judaism.” Faced with looming threats of intermarriage, synagogues had to find a way to ensure marital unions remained exclusively Jewish. One means of achieving this was to require that male congregants marry Jewish women. However, women were also tempted by non-Jewish suitors. To keep women in the Orthodox community and to create an environment where two young Jews could meet, the synagogue had to entice women to stay. This provides one explanation for the relatively liberal policies towards women at BCMH.  Another section of the constitution states, “The monthly dues of the congregation shall be six ($6.00) dollars per month… The monthly dues of the associate Women members of the congregation shall be one ($1.00) dollar per month.” This passage can further illuminate the excerpt we have examined. Women in the 1920’s didn’t have the employment opportunities available to women today, and as such couldn’t afford to pay the standard “family” (or single male) membership fees. It is possible that the associate memberships were created to allow unmarried women to participate in congregational life. The restrictions on voting and the “right to hold office in the congregation” can be attributed to unwillingness of the congregation to give women complete equal standing in the synagogue, reflective of the desire of men to maintain their traditional roles as decision-makers and leaders in the congregation. There is another interesting facet of the first selection from the constitution regarding membership.

Another section of the constitution states, “The monthly dues of the congregation shall be six ($6.00) dollars per month… The monthly dues of the associate Women members of the congregation shall be one ($1.00) dollar per month.” This passage can further illuminate the excerpt we have examined. Women in the 1920’s didn’t have the employment opportunities available to women today, and as such couldn’t afford to pay the standard “family” (or single male) membership fees. It is possible that the associate memberships were created to allow unmarried women to participate in congregational life. The restrictions on voting and the “right to hold office in the congregation” can be attributed to unwillingness of the congregation to give women complete equal standing in the synagogue, reflective of the desire of men to maintain their traditional roles as decision-makers and leaders in the congregation. There is another interesting facet of the first selection from the constitution regarding membership.

Let me call your attention to the first sentence “Any Jew, of the age of eighteen years or over, of good moral character.” The limitation of membership to those over eighteen provides further evidence of Orthodox acculturation into American society. In traditional Jewish law males are considered to be “grown men” and full members of the congregation immediately after their Bar Mitzvahs at thirteen years old. Because of this, membership should seemingly be extended to all men over Bar Mitzvah. So why eighteen?

In the American framework that the synagogue is established, men could only vote from the age of twenty one. This remained constant until the 26th amendment passed in 1971, lowering the voting age to eighteen. Thus, granting men “full rights” at thirteen would have been looked upon as absurd. The congregation’s willingness to define manhood (and membership to the synagogue) as significantly older than the commonly-held Jewish norm shows the modern, Americanized viewpoint of BCMH. Rather than disassociating from American culture, this policy shows adoption and integration into the American system.