Section of a woven map of the island of Rhodes. Zimbabwe, 1960. Courtesy of the private collection of Jeanine Graham.

Editor’s Note: This week, people from around the world will be gathering on the island of Rhodes to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Rhodes Jewish community’s deportation to Auschwitz during World War II. The following essay is offered as reflection not only on the 70th anniversary, but also on what it means to search for–and recreate–family history in the wake of a catastrophe.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

May 2006, the island of Rhodes. I pressed my hand against the cool, cream-colored stone of the elegant little house on Kisthiniou Street. No one was home, so I peered in the front window and covered my legal pad with notes. I had spent the morning traversing La Juderia, as the island’s Jewish quarter is known. Traces of the past were everywhere—Hebrew inscriptions carved into walls, pebbled floors in abandoned courtyards, narrow alleyways opening up to sun-drenched skies and sea.

Finally, I had arrived at the object of my pilgrimage, the house where my great-grandmother Estrella Galante grew up, one of eight children born to Rebecca Alhadeff and Samuel Leon, a winemaker. After months of online research and telephone interviews with older relatives around the globe, I had arrived at the foundational site of my family’s Sephardic past. The house was still standing; it was still beautiful; and it broke my heart.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

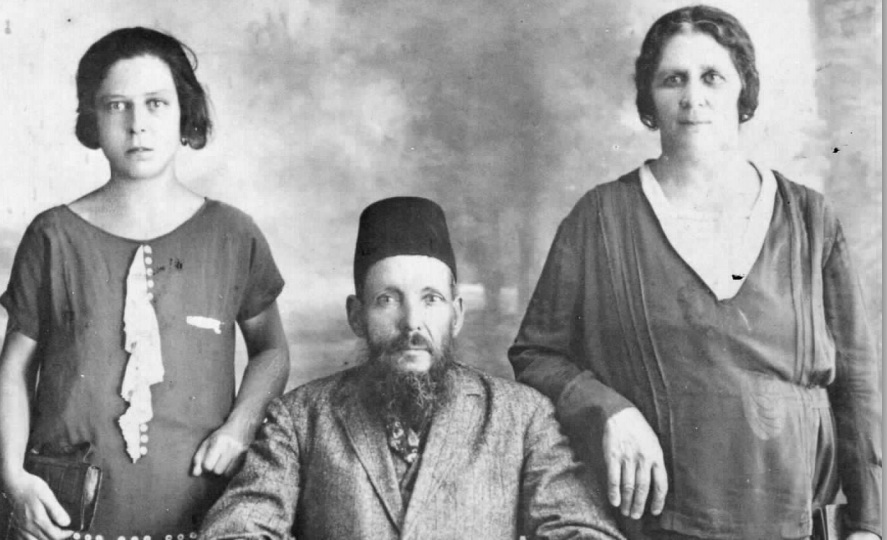

The author’s Sephardic ancestors on Rhodes: her great-great-grandfather Samuel Leon (seated center) with wife Rebecca Alhadeff (right) and cousin Vida Bonomo (left). Courtesy of the private collection of Vivienne Capelouto.

As a child in central Virginia, I already had a built-in sense of my parents being from elsewhere: they had grown up in Zimbabwe, in a bustling community of Jews who had immigrated from various places to find refuge and rebuild their lives in the British-run African colonies in the early 20th century. I knew well the narrative of my father’s family. They were Lithuanian Jews (known as Litvaks) who had lived in a shtetl called Pumpian (Pumpėnai), and they were among several thousand Yiddish-speaking Litvaks who ended up in Southern Africa.

The culture of Ashkenaz was the one that predominated at home, both linguistically and culinarily, when I was young. My grandparents sprinkled their conversations with Yiddish, and we celebrated Shabbat and holidays with typical Ashkenazi foods: chopped liver, herring, kichel, kneidlach.

Yet somewhere within me there was an awareness that my mother’s side of the family had a different story and an alternate set of Jewish cultural accoutrements. Once in a while, her distinct lineage surfaced. She had a way with phyllo dough and could make out-of-this-world spinach pies. There was also a small kiddush cup that sat above our dining room sideboard, engraved with her name as winner of the 1963 junior trophy from the “Sephardic B. and C. Youth Society.” She had antique evil-eye jewelry, and a set of superstitions that made my siblings and me giggle (but which we also followed, just in case).

And then there was the shoebox, which was kept on an upper shelf in my mother’s closet. It held a trove of family memorabilia—postcards, passports, documents, books, and photos. I must have been in college when I first started seriously scrutinizing the box’s contents, and it fired up my imagination. I was entranced by the black-and-white testaments to other people’s lives lived in distant landscapes. My great-grandmother Estrella perched on a horse in a dusty African yard, a twin daughter on either side. The same twins years later, now glamorous-looking young women with delicate features and dark wavy hair, feeding pigeons in London.

I peered at postcards with smudged ink, scribbled in a strange-looking script that I now know is Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish language that my great-grandmother, her Turkish husband, and their families spoke in their communities. I flipped through Estrella’s notebook of French exercises, covered with childishly looping handwriting, a relic of her girlhood that somehow survived intact. I studied her Italian passport—Italy wrested control of Rhodes from the Ottomans in 1912 and ruled it as a colony until the end of World War II—imagining what kind of journeys she would have taken from her island home in the 1910s and 1920s.

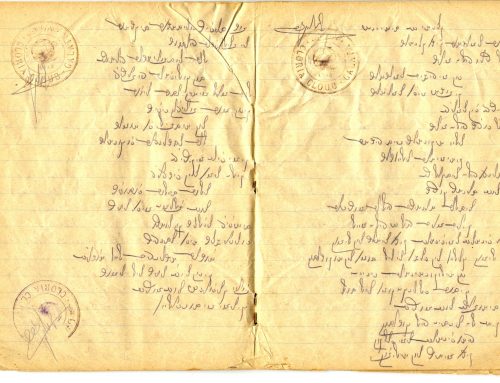

However, the item that changed everything about how I viewed my family’s past, and that spurred my quest to know more, was a one-page typed memo in Italian on stationary of the Jewish community of Rhodes, bearing official seals and signatures of Italian and Jewish officials. This is the document attesting to my great-great-grandmother Rebecca’s deportation from Rhodes. On July 23rd, 1944, 70 years ago this summer, she was one of nearly 1800 Jews from Rhodes and the island of Kos who were herded onto boats and eventually taken to Auschwitz.

Only about 150 Jews from Rhodes survived—a cataclysmic devastation of one of the world’s historic Sephardic communities. My great-great-grandmother Rebecca (also known as Rivka) was among the group that perished, selected on the first day she arrived at the concentration camp.

With this discovery, my family history intersected with the history of the Holocaust in a way that was painfully concrete. My childhood and young adulthood exposure to the Shoah was probably rather typical: I read books like Anne Frank’s diary and The Devil’s Arithmetic, saw “Schindler’s List” and “Life is Beautiful,” visited Yad Vashem on family trips to Israel and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum when it opened in Washington, DC. I participated in community and youth group Holocaust commemorations.

Yet when I looked at Rebecca’s deportation document, an official verification that the worst imaginable fate had happened to someone in my own family, someone whose picture was in my mother’s shoebox, all of the collective Holocaust narratives that I had acquired up until that point felt somehow more distant rather than closer to me. I felt a gap opening up in my heretofore-solid sense of Jewish identity, and an immediate, insatiable craving to know more about Rebecca’s life.

In that moment was born my desire to piece together as much of my Sephardic family’s story as possible, using any fragments and faded images that I could find, and talking to anyone who would release to me their valuable memories of the past. That desire led me in May 2006 to the house on Kisthiniou Street, the house where Rebecca raised her eight children, the house to which her husband Samuel the winemaker would arrive at the end of the day, arms scratched because he had fallen asleep on his donkey and run into some brambles along the way.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The artist Barry Salzman’s rendering of a gallery room where a virtual community is formed by life-sized portraits of descendants of Rhodes’ Jews. A walk-through of the installation is viewable on vimeo.com.

August 2013, the city of Seattle. Unaccustomed to a photographer’s scrutiny, I shifted my weight and stuck my hands in the pockets of my green dress. My younger son scampered around me on the dark portraiture cloth, tossing a ball and mugging cheerfully. On the other side of the camera was Barry Salzman, a New York-based artist who grew up in the Rhodesli community in Zimbabwe. He was visiting Seattle as part of his multi-city effort to collect as many video testimonials as possible from survivors of the original Rhodes Jewish community. Ultimately, Salzman reached 22 of the 45 Rhodesli Jews that he identified around the world, collecting over 100 hours of precious oral histories describing a vanished way of life.

Salzman’s project also involved taking photographs of 300 of the community’s descendants, which is why my son and I were posing together last August. Eventually, these life-sized portraits would be included as a composite mural to accompany the video testimonials. As Salzman explained it to me, the photographic mural in the gallery would create a virtual community of people who might still be living on Rhodes had the catastrophe not happened; it would also suggest an alternative reality wherein Rhodesli Jews are the majority in the room, not a nearly-extinguished minority culture fighting to preserve its past.

A walk-through preview of Salzman’s multi-media installation is viewable here, and “It Never Rained on Rhodes,” a 30-minute experimental film splicing together the testimonials, can be seen below:

It Never Rained on Rhodes from BARRY SALZMAN on Vimeo.

The film will be screened as part of a week of 70th-anniversary commemorative activities taking place on Rhodes in late July. The project’s executive producer, Lisa Capelouto, also grew up in the Rhodesli community in Zimbabwe. Noting the huge amount of material gathered by Salzman, she says, “The film is a tiny glimpse into the possibilities that this project could lead to.”

As the historian Aron Rodrigue discussed last year at the UW, for a dispersed and traumatized community like the Jews of Rhodes, the process of constructing memory is dynamic: each generation contributes new approaches to the community’s narrative of itself. Salzman’s project uses modern technologies, but his goal is ultimately old-fashioned. He allows individuals space to tell their stories, and brings those voices together (sometimes literally—their voices overlap at times in the video), so that the lightest and very darkest moments from the speakers’ pasts continually converge and diverge onscreen. In Salzman’s words, the film conveys “the universality of loss—loss of place, heritage, youth or cultural identity . . . through the lens of one small community that suffered unspeakable losses 70 years ago.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The author at the house where her great-great-grandparents raised eight children in La Juderia on the island of Rhodes. May 2006.

Though no one answered when I knocked on the door of my great-grandmother’s house eight years ago, the door to my family’s past has swung gradually wider. Living in Seattle, where Rhodesli immigrants founded Congregation Ezra Bessaroth in the early 20th century, has afforded me opportunities to meet long-lost cousins, to connect with valuable resources in the Sephardic community, and to start learning Ladino through the UW Sephardic Studies Program.

As might be expected, my search has yielded answers as well as questions, more leads to follow. I am doing this for myself, to know as much I can; and for my children, both of whom are named in memory of Rhodes relatives, so that they will know. And now, after years of staring at the black and white photographs of my Sephardic ancestors, a portrait of me in a green dress gazing down at my son is part of one artist’s imaginative recreation of the vibrant Jewish community of Rhodes.

Sifting through the rubble of the past is an act of hope: hope that we will find just one link to lives that have, by dint of time, geography, or fate, faded into obscurity. I am grateful to have found even more, and consequently, to have found myself a place within an unbroken lineage.

[…] as part of the American military. The Nazi Holocaust of the Jews during the Second World War destroyed entire Sephardic communities. The reaction of the Seattle Sephardic community during both wars was to enlist in the U.S. […]

This is intriguing to me. I, too, have tried to discover pieces of my Sephardic roots, which go back to Rodos [Galante – Alhadeff] and, before, that, to Rome. thank you for this. I’ll revisit it when I’m on my own time. 🙂 vjg

Thank you. The video-collage was very moving. Seeing Clement so close to tears saddened me deeply. All of them – those who remember well and those who remember almost nothing – are now in my soul.

Vickie Galante