(Left to right): Ketuba of Solomon and Leah Bensussen (Tekirdag, 1919); ketuba of Yisra’el Katarbas and Marat [?] bat Avraham (Tekirdag, 1900; courtesy Yale University Library); ketuba of Avraham Benezra and Rachel Halfon (Tekirdag, 1890).

Summary:

- The ketuba is a Jewish marriage contract exchanged at the wedding.

- Ketubot were not all the same: Especially among Sepharadim in the former Ottoman Empire, the text specified a variety of conditions.

- Writing and decorating the ketubot were distinct artistic disciplines.

- As Sepharadim moved from the Ottoman Empire to the Americas, ketubot were printed instead of handmade.

There are few decorations that immediately characterize a home as uniquely Jewish. Perhaps a mezuza (the covered scroll containing the text of the shema) affixed outside the house, would be the most indicative of the Jewish life within. But adorning many Jewish homes next to family photos and framed paintings hangs different kind of identifier: the ketuba, or Jewish marriage contract. Even without being able to decode the Aramaic text that is at the center of the ketuba, the decorative Hebrew verses surrounding its borders have signaled the Jewish identity of its owners for centuries.

But what about a ketuba with Isalmic iconography? What can we glean about a couple who adorned their home with a ketuba of this style?

What is the purpose of a ketuba?

The ketuba is one of the most important elements of a Jewish wedding. It is a legal document that stipulates a man’s obligations to his wife and details his responsibilities to her should they ever divorce, or what she will inherit if he passes away. Before the marriage ceremony, the ketuba is signed by two witnesses and then read aloud during the ceremony.

Do all ketubot say the same thing?

A common misconception about the ketuba text is that it was necessarily always the same. In fact, there is no stipulated formula for the ketuba found in Jewish law; even though it is traditionally written in Aramaic — the language of the Babylonian Talmud — it can be written in any language as long as the main legal components set out by the Talmud are accurately represented.1 By the Middle Ages, a vast corpus of published rabbinic literature containing formulas for ketubot was circulated throughout Ashkenazi and Sepharadi communities, and the text of marriage contracts became standardized.

Sephardic ketubot specified the bride’s dowry

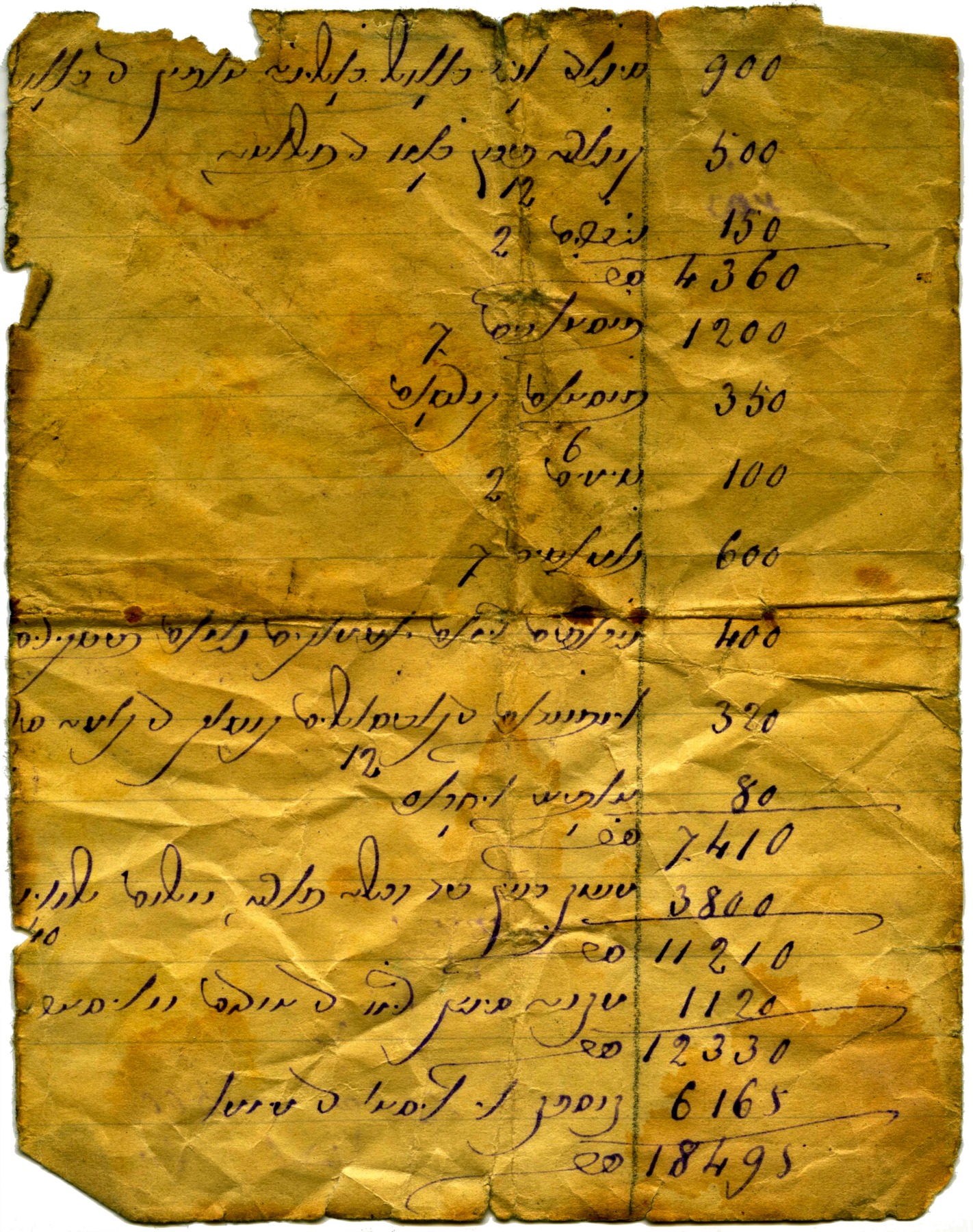

Fragment of a dowry assessment from the Jewish community of Rhodes, 1914. Courtesy of the Reverend Morris Scharhon Collection.

Sepharadi ketubot from around the world contained multiple variations, and much more often than Ashkenazi wedding contracts. One such variant was a detailed list of bride’s dowry. Instead of only listing the standard sum of dowry money determined by Jewish law, wealthy Sephardic families invested in expensive dowries as a status symbol. When this part of the contract was read aloud at weddings, all guests would know just how well-off the brides family was.

The dowries were not only recorded on the ketuba; in some places, such as on the Mediterranean Island of Rhodes, the Jewish community kept centralized records of their brides’ dowries.

Ketubot from the Ottoman Empire stipulated monogamy

In the Ottoman Empire, one of the most common insertions was added just before the end of the wedding contract. It stipulated that the husband was forbidden to take an additional wife. While the Bible does not forbid polygamy, Ashkenazi rabbinic authorities banned polygamous marriages around the year 1000.

But in the Islamic context of the Ottoman Empire, polygamy was legal until 1926. As such, ketubot from across the empire included an additional clause to remind couples of this prohibition (all ketubot featured here include this clause, and it is also found in ketubot from Salonica, Edirne, Izmir, and Rhodes).2 Even as the illuminations on the ketubot were drawn heavily from the styles of their Ottoman neighbors, the content of the contract maintained distinctly Jewish characteristics.

For Ester DeFunes and her daughters Estrea and Samhula (Allegra), the monogamy clause was vital in gaining entry into the United States in 1920. The elaborate golden ketuba shown at right was used by the DeFunes’ as the principal piece of identification when applying for travel papers from the Spanish Consulate to immigrate to the United States. It was critical that the DeFunes’ prove their adherance to monogamy in order to enter the country: restrictive American immigration laws barred anyone in a polygamous relationship from entering.3

Writing the ketuba text and decorating it were distinct disciplines

Ketuba of Sultana and Moshe Benezra, 1898. Note the scribal addition on the border. Courtesy of Rabbi Solomon Maimon.

Decorating and writing ketubot was usually a collaborative effort between scribe and artist. Painters would often decorate a ketuba as a template, and a scribe would fill in the contractual text later.4 Some surviving ketubot show potential evidence of this collaboration: at right, this ketuba from Rodoschik (present-day Tekirdag in Turkey) contains an error in the textual decoration in the right hand vertical column. This verse from the biblical Book of Proverbs appears to have originally been written without including the word barukh (Hebrew for “bless”), which was added in small black lettering among the larger, decorative verse. It is possible that the scribe — and not the artist — recognized this omission and made the addition later on.

The origins of decorated ketubot in Medieval Spain

While ornamented ketubot are now commonplace in most Jewish communities, decorating a ketuba first emerged as a distinctly Sephardic practice. Sepharadim have been decorating ketubot since at least the fourteenth century, when the Iberian rabbi Shimon ben Tsemah Duran (1361-1444) published a responsa, or rabbinic legal decision, saying that ornamented ketubot were not only permissible, but could actually protect the integrity of the document.5 Jewish law dictates that the two witnesses who sign the ketuba may only do so in specific locations below the main body of text; as such, decorated borders would prevent witnesses from accidentally signing elsewhere.

By contrast, no illuminated ketubot from medieval Ashkenazi communities survive today. The only ones preserved come from unions between Sephardic Jews living in those locales (such as Vienna and Hamburg).6

Although few examples of ketubot from pre-expulsion Spain survive today, Sepharadim brought their tradition of decorated ketubot with them beyond the Iberian Peninsula: there is a wealth of preserved marriage contracts from the Ottoman Empire that evidence a rich artistic milieu among Sepharadim who found their way to cities in Turkey and Greece following the expulsion.

Ottoman ketubot shared common artistic styles

Three ketubot from nineteenth and twentieth century Tekirdag (in header image, above), the outer two from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, exemplify the style found among most ketubot from that time and place: the outline is geometric, the lines confining the decorative text are bold and simple, and the illustrations are mostly floral. Additionally, the design is almost exactly symmetrical, perhaps an influence from Ottoman artists who also valued symmetry in their artwork.

Jewish artists in the Ottoman Empire often drew inspiration from Islamic iconography. By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Islamic artists in cities like Istanbul were drawing on inspiration from French artists and incorporating their post-impressionist styles into the more traditional, geometric style of Islamic art.7

Decorated ketubot expressed political allegiance

While illuminated manuscripts — such as bibles and prayer books — have survived from Jewish communities around the world, few creations that combined Jewish art and ritual would have been displayed publicly. The ketuba was unique in this regard, and therefore well-situated as a platform for celebrating political allegiance. Many of the ketubot in this section feature a crescent and star at the apex — an allusion to a similar Islamic symbol, but in reverse.

At the time these ketubot were created, the Ottoman Empire was on the verge of dissolving; by 1923, Istanbul and Rodoschik would become part of Turkey’s newly formed borders. Jews had enjoyed certain unprecedented privileges under Ottoman rule and generally able to practice their religion freely and openly — but what would the dissolution of the empire bring? With this uncertainty in mind, perhaps Sephardic artists began to include the star and crescent on their ketubot as a signal of acceptance and integration into the new government, whatever it may bring.8

In the Americas, the Sephardic ketuba transformed

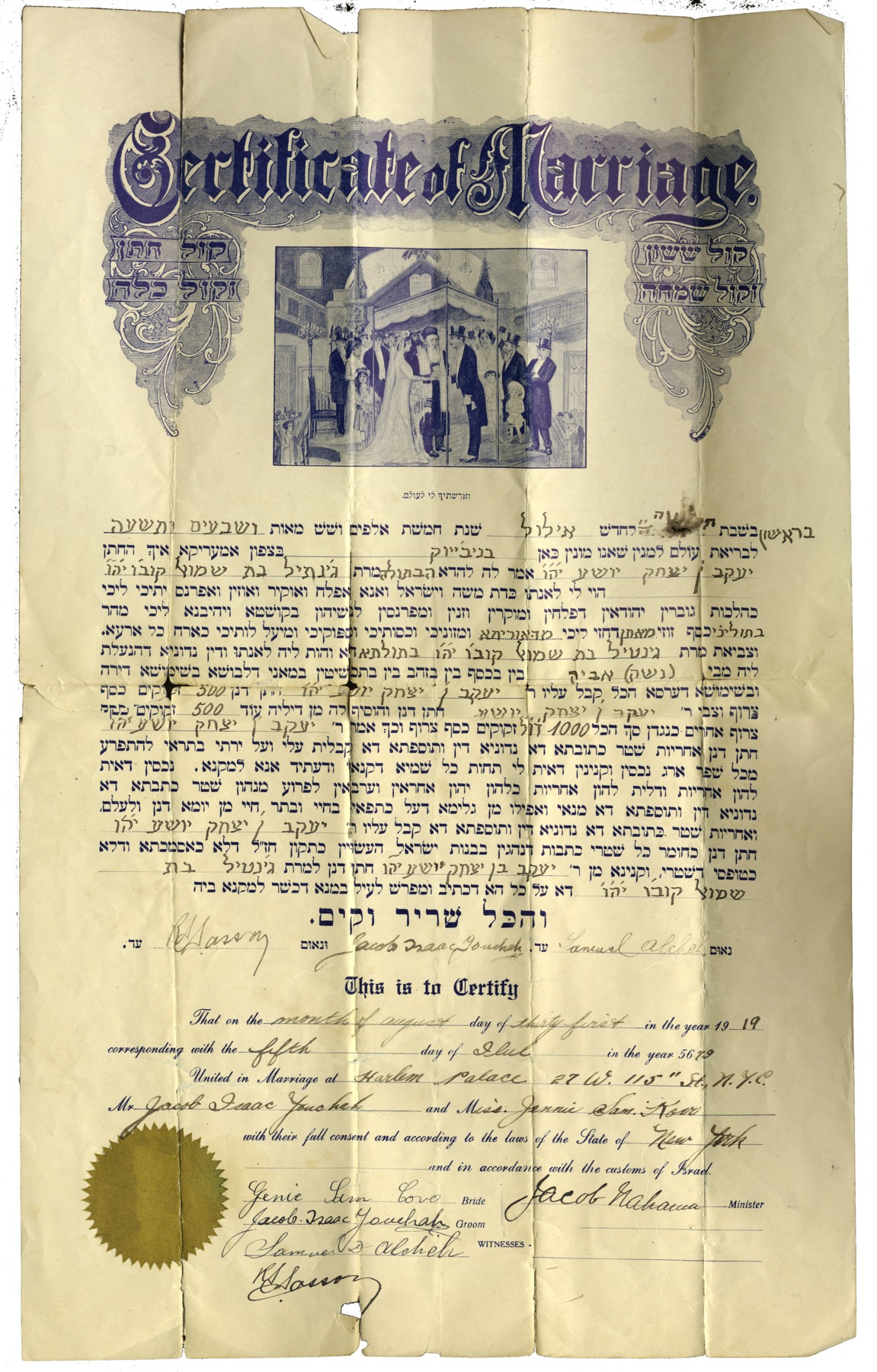

Ketuba from the wedding of Jenie Covo to Jacob Youchah in New York, 1919. Courtesy of Elayna J. Youchah

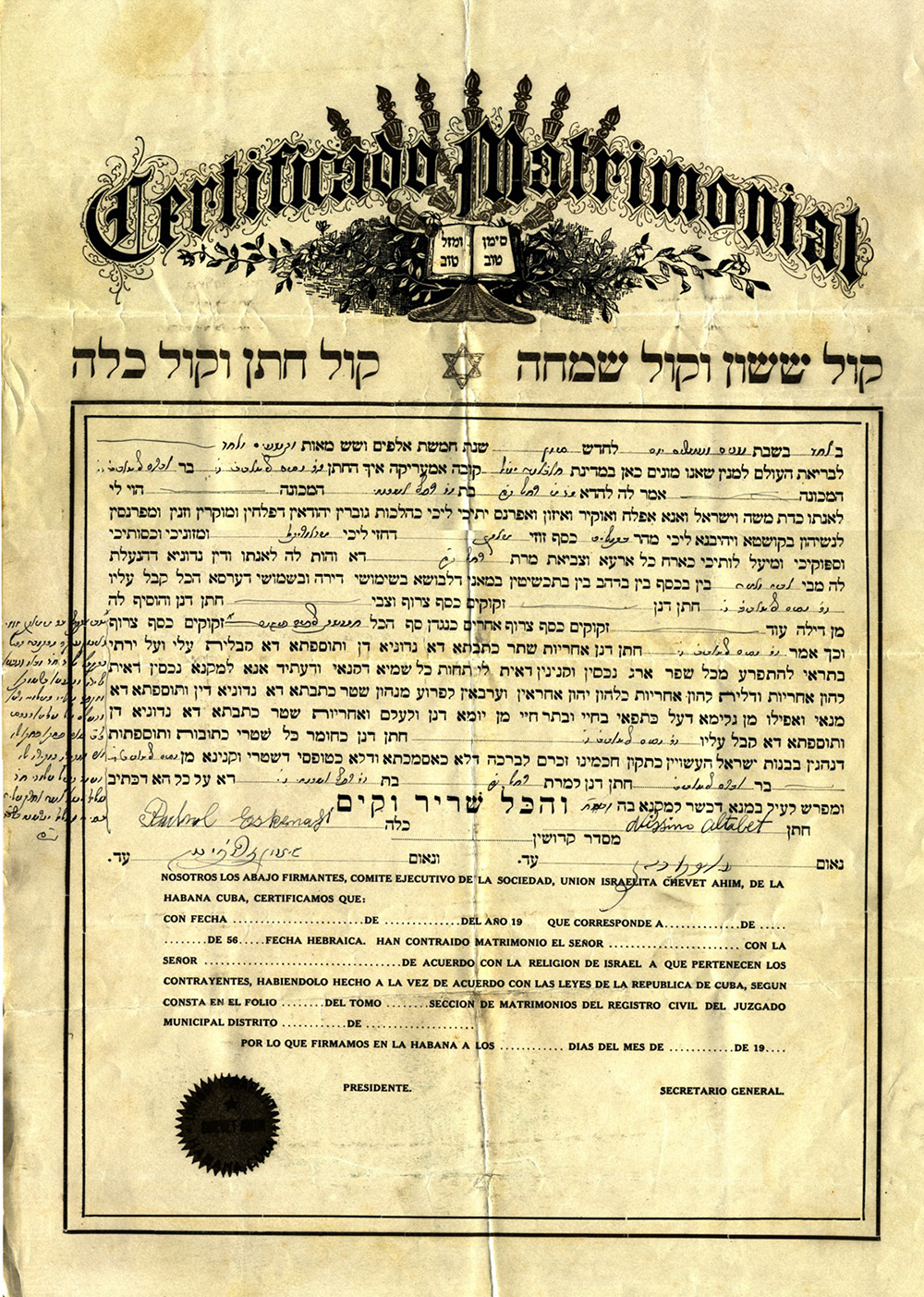

By the end of the nineteenth century, printed ketubot became commonplace. Just as one of the last handmade ketubot was produced in Istanbul in 1919 (above), printed marriage contracts were also the standard in North and South America. In some cases, the fact that these documents were ketubot became almost secondary, as they were restructured as official marriage licenses, such as the ones at right from New York and Cuba.

Instead of a star and crescent pledging political allegiance, both ketubot above are titled as Certificates of Marriage (or Certificado Matrimonial, in the case of the one from Cuba) and have a marriage license appended under the Jewish contract. Perhaps in an effort to bolster the legitimacy of the ketuba in the eyes of the American and Cuban governments, the Jewish contract had to be framed within the context of a marriage contract that was more recognizable.

Ketuba from the marriage of Rachel Eskenazi (Esquenazi) and Nissim Altabet in Cuba, 1931. Courtesy of Steve Hemmat.

Not only did advanced printing technologies eliminate the art of handmade ketubot, but the text itself also lost the customization once characteristic of Sephardic ketubot. The two ketubot at right, one from New York and one from Havana, Cuba, are both in the standard Ashkenazi formula even though both couples are Sephardic. With no concern for polygamy in either place, the additional clause commonly found across Ottoman ketubot was eliminated.

Decorating a ketuba — whether by hand or with printing technology — necessarily brings the document out of the private relationship between husband and wife and pushes it into the public eye. Why would artists take such care to illuminate ketubot if they were not meant to be displayed for all to see? When ketubot garner an audience, they become more than a contract used to legalize a Jewish marriage: They become platforms to express allegiance or garner acceptance, and provide a glimpse into the interaction between Jews and their neighbors around the world.

The Sephardic Studies Program would like to extend special thanks to Professor Shalom Sabar (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for sharing his expertise on Sephardic ketubot and contributing important historical context and translation efforts to this section.

References:

1. Sabar, Shalom. The Beginnings and Flourishing of Ketubbah Illustration in Italy: A Study in Popular Imagery and Jewish Patronage During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1987. 20

2. Sabar, Shalom. “Decorated Ketubot” in Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture. Ed. Esther Juhasz. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1990.

3. Alhadeff, Ty. “The Benezra collection: A Seattle Sephardic legacy.” Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. May 19th, 2019.

4. Sabar, Shalom. “Decorated Ketubot” in Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture. Ed. Esther Juhasz. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1990. 221.

5. Responsa of Shimon ben Tsemah Duran, Sefer Tashbets, part 6:

ולפי זה ישר בעיני מה שנהגו בכתוב’ חתנים לצייר בציורין ופסוקי’ בגליון לפי שנהגו לעשו’ גליון גדול לנוי ומלאו אותו באותן פסוקי’ וציורין בשביל שלא יחתמו העדים בראש שטה תחת שטו’ הכתובה וישאר גליון פנוי

6. Sabar, Shalom. “Decorated Ketubot” in Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture. Ed. Esther Juhasz. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1990.

7. Ibid.

8. Naar, Devin. “Jews, Muslims, and the Limits of Tolerance.” Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. November 21, 2016.