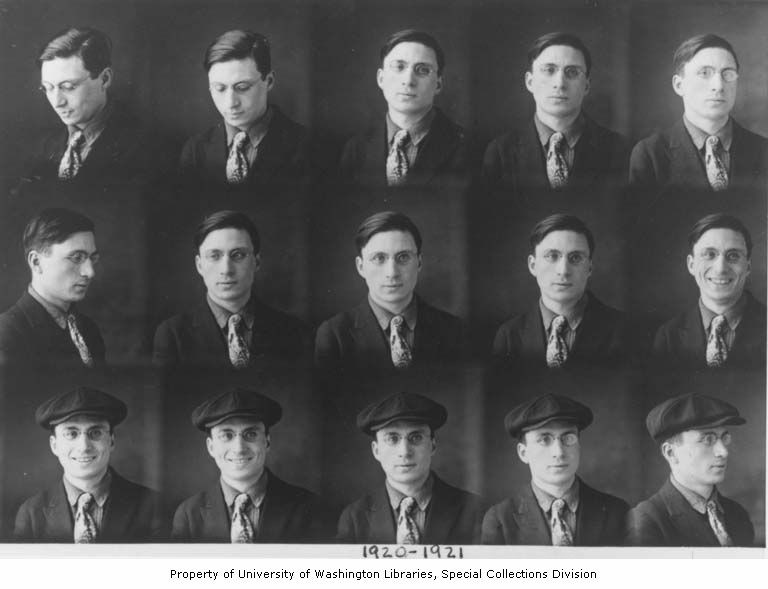

Sequence of portraits of Henry Benezra, 1920-1921. Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Washington State Jewish Archives Photographs.

By Ty Alhadeff

Over a century ago, Sephardic Jews packed their steamer trunks with clothes, provisions, photographs, and books to make the long voyage from the Ottoman Empire to Seattle. Leaving behind their parents and friends, they never could have dreamed that one day these same books and other family heirlooms would be part of the Sephardic Studies Collection at the University of Washington.

Jewish marriage contract. Esther Benezra and David DeFunes. Ottoman Empire, 1888 (ST01600, courtesy Albert Maimon/Henry Benezra Collection)

The collection of Henry and Samhula Benezra encapsulates the trajectories of Sephardic Jews over the generations and the connections they developed across multiple cultures and geographies. Benezra himself was the first member of the Seattle Sephardic community to graduate from the University of Washington and was an avid writer, composing original (unpublished) Sephardic works and contributing articles to Seattle’s Jewish Transcript. Benezra also amassed Sephardic prayer books, bibles and other manuscripts from across the Ottoman Empire.

Included among the items in his family collection are several important documents from his wife Samhula’s parents. A beautifully ornamented Jewish wedding contract (ketuba), signed in 1888 in Rodoschik, the Ottoman city of Rodosto (present-day Tekirdağ, Turkey) and surrounded by verses from the Torah, is uniquely adorned with the star and crescent moon, symbols of the Ottoman Empire and of Islam. This ketuba is significant not just because of its aesthetic qualities that merge Jewish and Ottoman imagery, but also because the Aramaic text specifies the monogamous nature of the marriage—a noteworthy addendum given the Ottoman Turkish context in which polygamy remained legal until 1926.

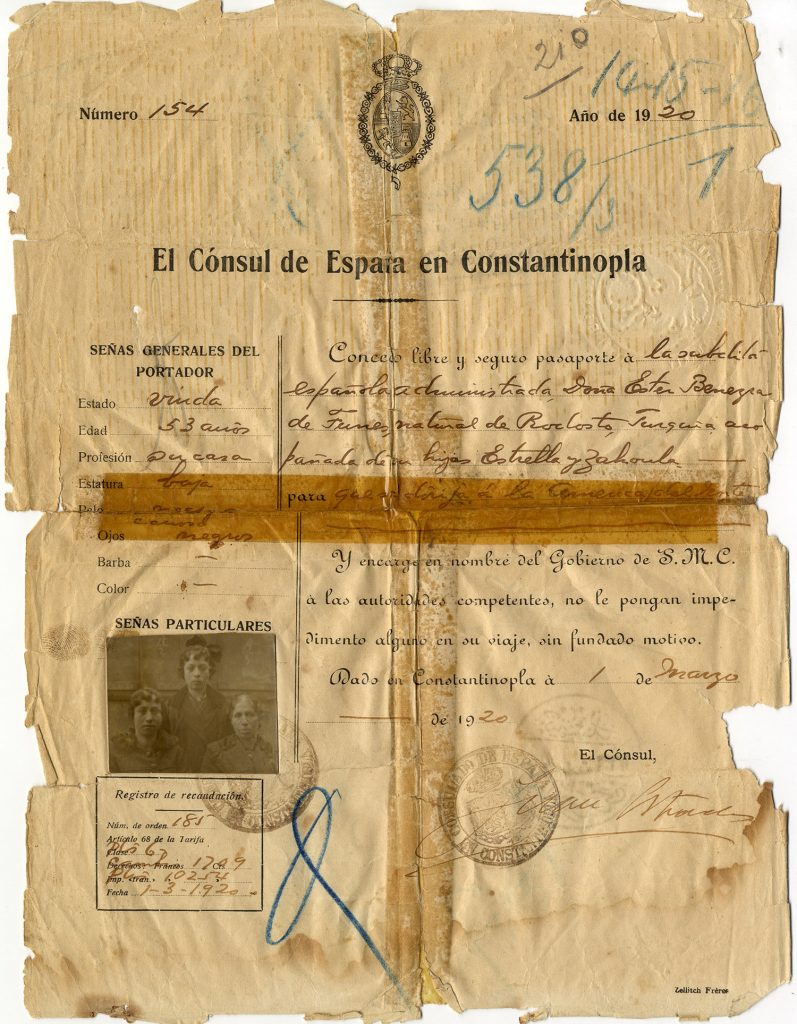

Spanish passport for the DeFunes family, Istanbul, 1920 (ST01965, courtesy Al Maimon/Henry Benezra Collection)

As significantly, the ketuba served as the principal piece of identification for Ester DeFunes and her daughters Estrea and Samhula (Allegra) when they applied for a passport to travel to the United States in 1920, after World War I. Despite the family having viewed themselves as part of the Ottoman environment at the time of the wedding, the changed circumstances decades later provoked them to acquire travel papers from the Spanish Consulate in Istanbul. By that time, the Spanish government had begun its effort to recruit Sephardic Jews (recently renewed with the Spanish citizenship law of 2015). Clearly, the DeFunes clan took advantage of the opportunity. Due to restrictive immigration laws in the United States that targeted Asians and Middle Easterners—and barred those in polygamous relationships—it was easier for the DeFunes family to enter the country as Spaniards than as Ottomans.

The trajectory of the Sephardic Jews is often envisioned as a five-century saga from the expulsion from Spain in 1492, to the resettlement in the Ottoman Empire, and then the out migrations to the United States and elsewhere in the twentieth century. These two DeFunes artifacts illustrate an even more complex and winding path, with the biblically-inspired text of the Ottoman ketuba enabling their acquisition of Spanish papers that linked them to the ancestral land of Spain, and permitted their entry into yet another land—the United States. The showcasing of more stories such as the DeFuneses signifies the complex journeys of many Sephardic families as they made their way to Seattle.

Special thanks to Al Maimon for providing the Henry and Samhula Benezra collection, courtesy of their daughter, Sarah Benezra.

Editor’s note: The original version of this article appeared in the “Unique Areas of Expertise” section of the Stroum Center’s Jewish Studies Impact Report, Autumn 2018. View the entire report here.

Further reading:

- Share your story with the Sephardic Studies Program by Makena Mezistrano (2019)

- Sephardic Studies and the boundaries of Jewish Studies: A year in review by Devin E. Naar (2019)

I am a benezrah from Tangiers

Regards

I am isaac benezra benezra and I was born in tangier regards