Eighty years ago, nearly 3,000 Americans embarked for Europe to join the democratically elected Spanish Republic in its effort to repel a military coup led by Francisco Franco. Franco had the support of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. The Republic received aid from the Soviet Union and from the International Brigades, including what came to be called the Lincoln Brigade of American recruits. Nearly one-third of the Americans who went to Spain were Jews.

In the early ’90s, Professor Joe Butwin interviewed dozens of these Jewish veterans, collecting their stories and inviting them to reflect on the connection between their Judaism and their decision to serve in the war. He explains:

“In 1992, a few months after the fall of the Soviet Union, I traveled coast to coast with a cheap tape recorder and interviewed forty Jewish men and women who had made the trip to Spain in 1937.

Interviewer Joe Butwin in 1992, wearing a cap from the American Lincoln Battalion

My project started with a narrow set of questions that began to change the moment I sat down to talk with people in their homes, at cafes, and on park benches. I came to them equipped with questions about Spain in 1937: Why did you volunteer, and did your decision have anything to do with being Jewish? Those were not necessarily my exact words, but that was the point. That’s what they had in common: they were Jews who had served the Republic in the Spanish Civil War.

What emerged from our conversations was the collective biography of a generation. Their stories are distinct; they may converge only in Spain before they diverge again. But within those distinct and diverse paths are patterns that began to clarify themselves in new ways as I read through the transcripts 25 years after the fact: immigration, absorption, and alienation, as Americans, as Jews, as Communists — followed by retrospection that made them eager to talk it over with a willing listener.” Learn more about the origins of this project >

In advance of Professor Butwin’s forthcoming book collecting these interviews, hear from five of the men and women who risked their lives to fight fascism:

George Watt in 1938

At first, George Watt (1913-1994) hesitated to put his life on the line. Soon he knew he had to go: “I was afraid our history was going to pass me by.” For Watt, originally Israel Kwatt, “our history” began as family history. Hear more of George Watt’s story >

“As long as I can remember there was a legend in our family around my grandfather, my father’s father. My father’s father was a textile worker, a weaver, in Lodz and he worked in a factory which was owned by a Jewish boss. His factory was the place where they had the first strike of Jewish workers — Lodz — in 1903, at the Shlitsky factory in Lodz. And ever since I was a kid my father told a story which was part of our family tradition.

He was not a rabbi, but he was considered very learned and was called Avremele der lamden, Abraham, the learned one, and he was one of the elder workers in the plant who became active in this strike, and he was one of the leaders of the strike. Not the leader, but one of the leaders. And my father always told this story and he said how they were arrested by the Tsarist police because this was Russian Poland then. And he described how he as a six year-old boy watched his father being taken in shackles and the punishment in those days was they forced you to walk on foot back to your village of origin.

See, many of the people living Lodz had immigrated from the smaller outlying surrounding villages into Lodz where you had industry, and they became workers and so on. And he had to move back to his home shtetl in kaytn, in chains.

And this was the story I always remembered. And so that was part of our tradition. In other words, my grandfather, the pride that we had, my grandfather had led the first strike of Jewish workers in Lodz. 1903. That was around the time leading up to the 1905 revolution. So that’s part of our tradition.”

Bill Susman in 1938

George Watt’s friend, Bill Susman (1915-2003), went to Spain as “Bill Ellis.” He grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where his family spoke Yiddish, and he went to the Yiddishe shul where Biblical stories and Yiddish folk tales were taught as parables of class struggle. Hear more of Bill’s story >

“My recollection of the political world which starts about 5 or 6 years later — 1921, perhaps 1922 — was that people would come to our house for meetings and they would engage in hot debates and arguments about who was right— Trotsky or Lenin or Bukharin, whom I was convinced and persuaded were all Jews.

After all, the reports about what they were saying came through in the Jewish press and they all seemed to speak Jewish [Yiddish] perfectly, so I was persuaded that they were all Jewish. And I was very pleased that there was a country where all the leaders were Jews!”

Celia Seborer and medical pioneer Norman Bethune in 1936

Celia Seborer (1907-2005), a lab technician and then a nurse, was the first woman to volunteer for service in Spain when she joined her husband, the journalist George Marion. She and Maurie had already been to Spain in 1934, and they saw Hitler’s Berlin in January of ’35. Hear more of Celia’s story >

“I knew it too well; in that first trip to Spain we left there December 1, let’s say, and were in Europe through [early] 1935. We came up through Spain into France to Paris where we had some friends and, that was ’36.

We applied for visas to the Soviet Union and I was going to see Rachiel [her father’s cousin]. That was for me, and I said “laboratory technician,” and Maurie wrote “writer.” My visa came through promptly and his didn’t come, didn’t come and he decided we’d go to Germany. This was long before the women’s movement; it would have been otherwise.

So we went to Germany, to Berlin, and in a few days, we were expecting to go to Moscow. Rachiel was expecting us, and I said, I’m going. I can’t stand this Juden Verboten business… So I picked up and left, took the train, went to Warsaw, spent the night there, part of a day, and went on to Moscow and was met at the station by Rachiel. There was no question about being anti-fascist.”

Sana Goldblatt in 1938

Sana Goldblatt (1915-2003), born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, was a nurse, recently trained at Beth Israel Hospital in New York, when she volunteered to go to Spain to serve in the Medical Unit under Dr. Edward Barsky, also from Beth Israel. In the frozen terrain at Teruel in January and February 1938, she served at the front. Hear more of Sana’s story >

“The most amazing thing to me was a big van called an autochir—chir being surgery? This was a French tremendous thing. It had everything you needed for surgery. Everything. Behind that came trucks with beds, mattresses, sheets, etc. All the stuff you would need for nursing. And behind that, of course, came the guy who foraged for food. You have to bring all these things along.

I worked with one other woman who was in charge of surgery. She and I managed the whole thing. You could use the van because it had its own generator. They had this big operating room table in the center of it. Everything was outfitted, every space in the wall had a place. For hemostats, for sutures, for bandages, for instruments. Everything had its place so that you could put your hand on anything in this small truck. Mainly, we did not work in the truck.

When we got into a city and it was close to the frontline what we did was find a house. One of the places we used a stable – the house was above the stable, the stable below. That became the surgery. You pulled the table out, you pulled everything you needed out. Even your operating room gowns and mask – everything was in there. So you pulled in and you could start working.”

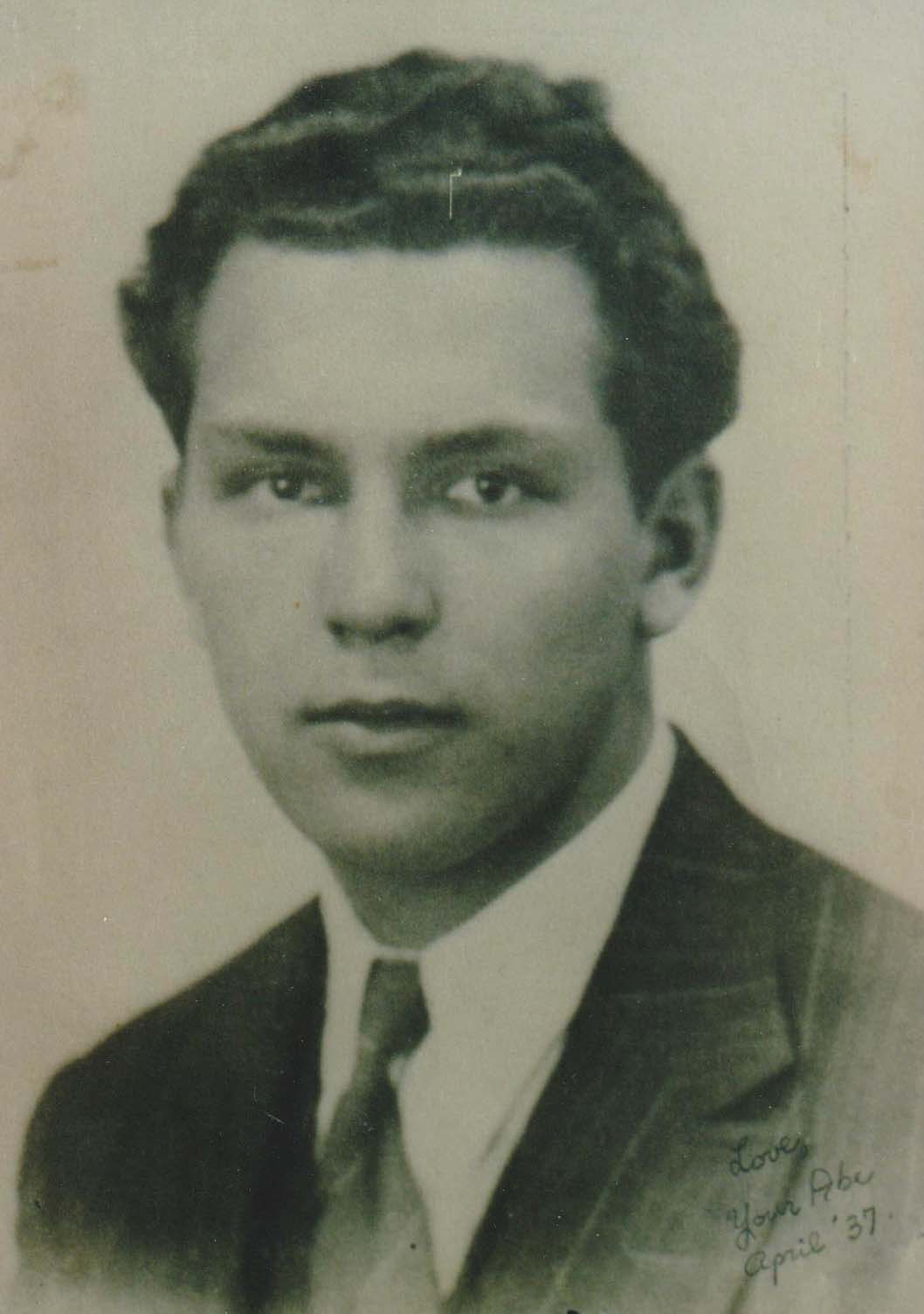

Portrait of Abe Osheroff in 1937

Abe Osheroff (1915-2008) was raised in Brownsville, Brooklyn, an almost entirely Jewish enclave that absorbed most of his attention as a Young Communist and community organizer before he went to Spain in 1937. Hear more of Abe’s story >

“You have to keep in mind that in 1936, three years after he came to power, or two and a half, the Holocaust was not yet going on. There was some pretty shitty anti-Semitism in Germany, but so was there in Poland, and in Hungary, and in Romania, you name it. We didn’t know that it was so in the Soviet Union yet.

We were aware of that [anti-Semitism], but it didn’t have a tiny particle of the influence that the Holocaust would have when we became aware of it—by ’40, ’41, the liquidation. Before that it was harassment, economic, political cultural harassment… the occasional bumping off, but it was not yet the official German policy.

Judenrein [to void Germany and then Europe of Jews, extreme ethnic “cleansing”] was not even an expression yet, even in Mein Kampf he doesn’t talk about Judenrein. So this issue wasn’t even thought of very very much… Except there was a large handful of guys whose primary language was still Jewish — Yiddish. They asked the International Brigades to form a separate Yiddish-speaking detachment. It was granted. About 200 guys volunteered to be in that. And that was how the Botvin Company was formed.”

About Jews in the Spanish Civil War

Photograph of one platoon of the international Lincoln Brigade. From the collection of Ed Lending (center bottom).

If Jewish men and women accounted for nearly a third of the volunteers who went to Spain from the United States, the numbers are no less striking when it comes to the volunteers from other countries. Of the nearly 40,000 members of the International Brigades, at least 7,000 were Jews, many of them Polish refugees embedded in French, British or Belgian units. American nurses were able to communicate with colleagues from other nations in the mama-loshn, Yiddish. The same was true for couriers at the front.

At the end of 1937, an entirely Jewish unit was formed on the initiative of influential members of the émigré community in Paris. The Botvin Company of the Polish Dombrowski Battalion was named for Naftali Botvin, a Polish Jew and a Communist who was tried and executed for the murder of a police spy in Lvov in 1925.

From interviewer Prof. Joe Butwin:

“The name of the company, Botvin, is the same as my own slightly Anglicized version—Butwin—and this helped me through the door with many of the Vets who, like George Watt at Yad Vashem, had come to see their action in Spain as part of the long history of Jewish resistance to tyranny.”

Learn more about the origins of the “Salud y Shalom” project >

Explore the stories: