Bill Susman, Soldier, 1915-2003

- What was it like to grow up as a Jewish Communist?

- What were some of the risks of being an active Communist in the ’30s?

Bill Susman in Spain, 1938

George Watt’s friend, Bill Susman, went to Spain as “Bill Ellis.” He grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where his family spoke Yiddish, and he went to the Yiddishe shule where Biblical stories and Yiddish folk tales were taught as parables of class struggle.

What was it like to grow up as a Jewish Communist?

Bill. We had various courses, one was history — geshikhte, that’s what it was called. It was really the Bible because you were told all the stories of the Bible and the Exodus and all that, without religious overtones, simply as facts. They were far from facts, but given to us as facts and we accepted them as facts.

And then we had classes in literature where we read Sholem Aleichem and all the Jewish writers and poetry as well. Every year there was a program put on usually at a high school. […]

We kids used to go up and do readings and recite poetry. When I recited Di tvai brider — “The Two Brothers” — I was absolutely persuaded that this was really a story of the class struggle. I now realize that the writer had in mind much more than class struggle, because the serpent that is the central figure there was also a Biblical figure and he had in mind this poisoner of the well for all humanity. But nonetheless to me it was a clear-cut story of the origin of class struggle.

Bill. [As for that kind of thinking] I was born into it. It was our table talk. […]

My father would read us stories about Russian children and about their participation in the Revolution and the rear guard actions that they carried out or their special assignments or the messages they carried.

My brother and I envied them their bravery, their courage, the high adventure that they all had. And they always prevailed. We loved those stories.

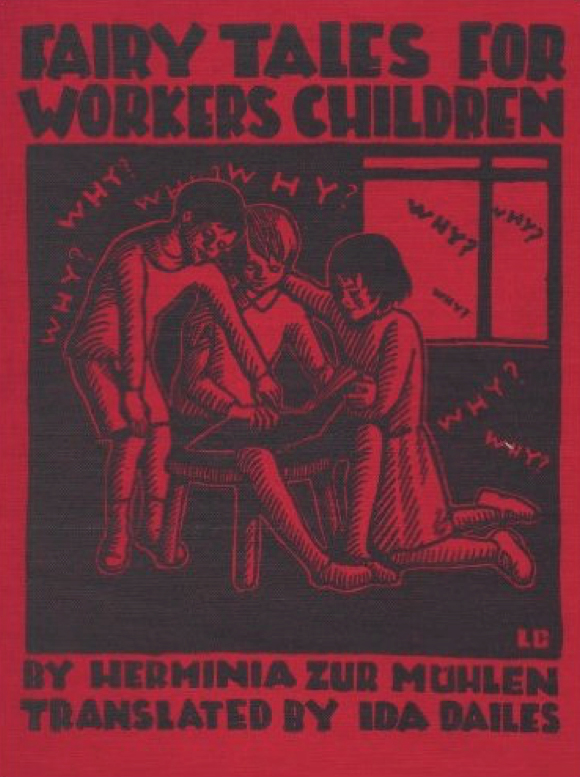

There was an English translation of them that was published as Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children. It was a great big book with a big red cover and plenty of illustrations.

Bill. That was on one level. Another level was that my father and mother were both charter members of the Workers’ Party of America, which later went on to become the Communist Party. It was the first split from the Socialist Party on the issue of World War I.

I was born in 1915. My recollection of the political world which starts about 5 or 6 years later — 1921, perhaps 1922 — was that people would come to our house for meetings and they would engage in hot debates and arguments about who was right — Trotsky or Lenin or Bukharin, whom I was convinced and persuaded were all Jews.

After all, the reports about what they were saying came through in the Jewish press and they all seemed to speak Jewish [Yiddish] perfectly, so I was persuaded that they were all Jewish. And I was very pleased that there was a country where all the leaders were Jews!

Bill. Our home was always the place where speakers would stop and stay when they came to deliver speeches. I developed friendships with people like Zayde (Grandfather) Winchevsky. I have a photograph of myself in my little Russian blouse, sitting on his lap with my Buster Brown haircut, corduroy pants and all sorts of speakers, like Scott Nearing who I also thought was Yiddish. I didn’t know.

Joe. A number of people that I’ve talked to — and now I’m going to use a religious term — had a kind of conversion experience to Communism or to the left. You know, suddenly they see the disaster of the capitalist system, it slaps them in the face because of the Depression, because of some horrible event in their own family — you know, a parent dying for want of medical care, something like that. I don’t guess you had a conversion experience!

Bill. Never did. I never had the opportunity. [Other guys were] indignant about what was happening in Spain. I was never indignant. I expected it. I thought, well, of course, that’s how people are. And if you asked me why I went to Spain, I would tell you I was born to go to Spain because with this background there was nothing else in my future but to do precisely that. I wouldn’t have been carrying out my program had I not gotten involved.

What were some of the risks of being an active Communist in the ’30s?

Bill’s boyhood friend, Harry Eisman, was not an American citizen when he was arrested at a Communist demonstration in 1930. He was sent to Hawthorne Reformatory, where Bill visited him every Sunday.

Harry was eventually permitted to go to the Soviet Union before his 5-year sentence was up. Bill and his father drove him from Hawthorne to the ship; the following May Day, Harry was pictured in the newspapers with Stalin beside Lenin’s tomb.

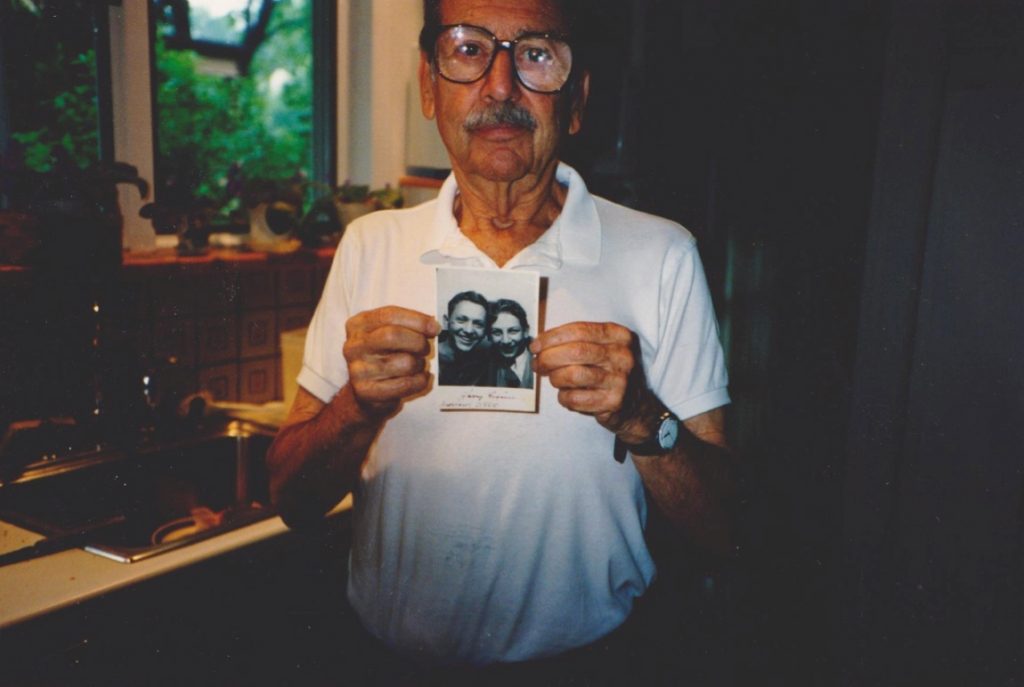

In this picture, Bill Susman, at home in Great Neck, Long Island, in 1992 shows a picture that his friend Harry had retained in the USSR throughout World War II and his time in prison in Siberia. Harry gave the photo back to Bill in Moscow years later. The photo was taken in 1930 in New York, before Harry was arrested, when they were both Young Pioneers — Young Communists.

Bill Susman was not as durable an adherent to the Soviet Union or to Communism as his friend Harry Eisman. He left the Party in the 1950s and suffered the usual harassment from the FBI, but never gave up his basic principles, which he pursued in a variety of ways up to the time of our interview.

The personal and professional association that he and his wife Helene maintained with the progressive documentary filmmaker Barbara Kopple was one expression of those principles. The two-day interview began with a discussion of the two films that Kopple had made about controversial strikes in the coal and meat-packing industries (Harlan County U.S.A., 1976; American Dream, 1990).

Explore more stories: