Summary:

- Jewish circumcision, or berit mila, is an ancient biblical commandment.

- The ceremony involves many players, including the mohel who circumcizes the baby boy, and several family members.

- Folk practices were once prevalent in Sephardic circumcision ceremonies but have declined in the United States.

In the above clip from Island of Roses (1995) — a documentary film about Jews from the Island of Rhodes who fled during World War II and settled in Los Angeles — Neil Sheff, a Los Angeles resident, explains his desire to recuperate Rhodesli traditions for his son’s berit mila, or circumcision. Sheff’s longing to understand and implement the Sephardic practices that had been in his family for centuries represents the ongoing search by Sephardic communities in the United States to reconnect with longstanding traditions. While the berit mila is one of the oldest Jewish traditions, some of its elements have changed and adapted to different cultural contexts. The ceremony now presents a space for the current generation of Sepharadim to explore those traditions that developed in the Ottoman context hundreds of years ago.

The biblical origins of Jewish circumcision

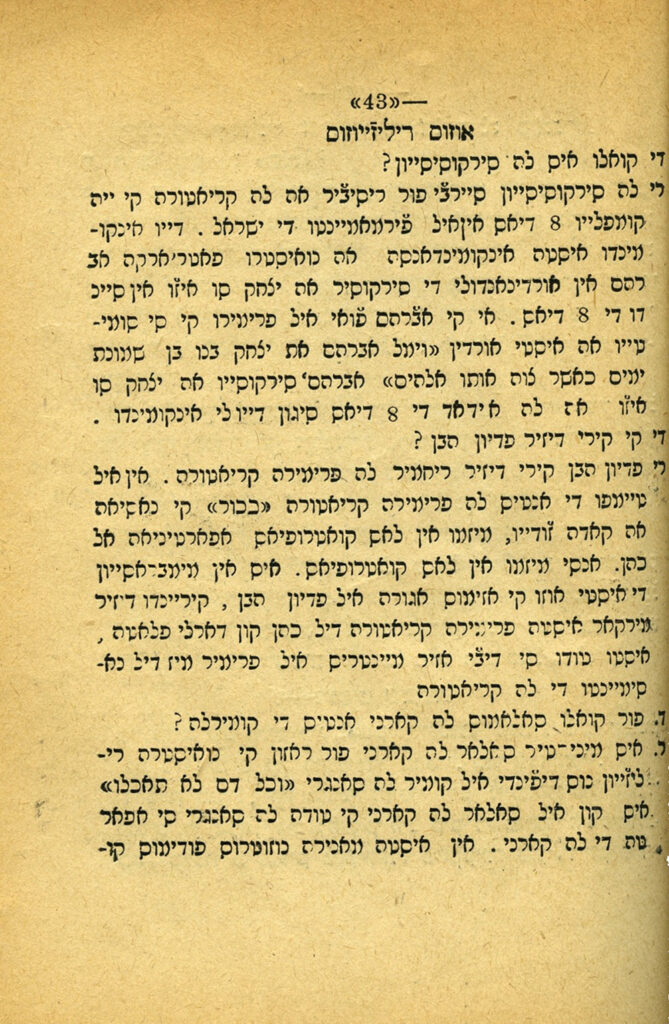

Circumcision of all boys is one of the most important life cycle events in Judaism. Livro instruksion religioza (Izmir, 1910), a religious instructional book for students at the Alliance Israélite Universelle — a French school system that included Jewish education and swept through the Ottoman Empire in the twentieth century — concisely describes the origins of the berit mila.

Although the work was intended for students at the Alliance where the mission was to Europeanize students, particularly through French language instruction, the book is written in question-answer format in Ladino, which was many of the pupils’ first language:

Kualo es la sirkonsisyon?

La sirkonsision sierve por risivir a la kriatura ke ya kompyo ocho dias en al fermamiento de Yisrael. Dio enkomendo esta enkomendansa a nuestro patriarka Avra’am en ordenandole de sirkosir a Yitshak su ijo en siendo de ocho dias. I ke Avra’am fue el primero ke se sumetio a este orden ‘va-yimol Avra’am et Yitshak beno ben shemonat yamim ka’asher tsiva oto Elohim.’ Avra’am sirkosio a Yitshak su ijo a la idad de ocho dias segun Dio le enkomendo.

“What is circumcision?

Circumcision serves to welcome a child who is eight days old into the community of Israel. God commanded this to our patriarch Abraham when he told him to circumcise his son Isaac at eight days old. Abraham was the first to submit to the order: ‘And Abraham circumcised his son Isaac when he was eight days old as God had commanded him.’ [Ladino Translation of the Hebrew:] ‘Abraham circumcised Isaac his son when he was eight days old just as God commanded him.'”

With the commandment of circumcision, Avraham became the first monotheist in the polytheistic ancient Near East. Ritual circumcision also marked God’s covenant with Avraham, in which God promised that Avraham would be the progenitor of the entire Jewish nation. As a testament to this covenant, Jewish communities around the world still circumcise male children at eight days old.

Who performs the circumcision?

Ladino explanation of the circumcision ceremony from Livro de instruksion religioza (Izmir, 1910), a religious guidebook for students.

Just like Avraham circumcised his son Yitshak, the biblical commandment to circumcise a male child technically falls on the father. Today, however, most Jewish men are not trained in ritual circumcision; instead, rabbis are professionally trained to become a mohel.

In the following clip from the documentary film Song of the Sephardi (1978), which was filmed in Seattle, Rabbi Solomon Maimon, rabbi of Sephardic Bikur Holim, acts as a mohel in a mock berit mila. When the child is brought to him, Rabbi Maimon recites a Hebrew blessing which describes the act of circumcision as the baby’s official entry into the covenant of Avraham — a direct reference to the first circumcision performed by Avraham in the bible. While Rabbi Maimon as the mohel recites the blessing, it could also be said by the baby’s father if he were acting as mohel.

Beyond his performance in the documentary, Rabbi Maimon was actually a professionally trained mohel and performed hundreds of circumcisions during his career — and even circumcised his own son, just as Avraham did to Yitshak. In the following clip, Rabbi Maimon also describes the immense trepidation he experienced the day he circumcised his son.

Family members participate in the ceremony

While the mohel certainly plays a vital role in the berit mila, the Me-am Lo’ez, a commentary on the bible and encyclopedia of Sephardic customs, argues that there is perhaps a role that is even more important: that of the sandak, also known in Ladino as the kitado.

The sandak, or female sandaka, is the godparent, and their role in the berit mila ceremony is also prominent: Holding the baby on a special pillow reserved for circumcision ceremonies, the sandak ceremoniously brings the baby to the mohel to be circumcised and often remains next to the baby for the duration of the ceremony.

Although anyone may technically serve as the sandak, the roles are often predetermined and stay within the family: For the first male child, the paternal grandparents are given the honor of sandak and sandaka; for next male child, the maternal grandparents are honored.

See the kitada (godmother) in a clip from Song of the Sephardi:

Folk practices were included in circumcisions

As Sheff notes in Island of Roses, there are several elements that are unique to a Sephardic berit mila. One of the most noteworthy customs associated with this life cycle event is the use of ruda, or rue, to keep the evil eye (ojo malo) at bay.

Just as Sheff describes in the film, the ruda is placed on the special berit mila pillow right next to the baby. This dovetails the custom of placing ruda next to the mother’s head as she sleeps just after giving birth.

As a person continues throughout their life cycle, the rue follows them: At a pidyon ha-ben, the ceremony to redeem the first born son, rue was a sweet smelling item that highlighted the celebratory occasion; at a wedding, rue was also sometimes used to mark the similarly joyous event. While rue is classified as a means of preventing evil spirits at the berit mila, it was also a symbol of joy and celebration at other life cycle events.

Are these folk practices still incorporated today?

Sheff’s own comment about the use of ruda during the berit mila reflects a certain discomfort that developed among Sepharadim in the United States regarding folk practices; as Sheff relates, “We’re not superstitious, but we still worry about these things.”

When Sepharadim came to the United States from the Ottoman Empire, their origins were often not seen as Jewish, but rather Muslim, Orientalist, and foreign. The perception — both by American Christians and sometimes even Ashkenazi Jews — of immigrants from a Muslim empire was that their customs were bizarre, backward, and represented a lack of sophistication. In order to fully integrate into American society many Sepharadim became self-conscious of those traditions that defined them as foreign in their new American home.

While Sheff’s comment from Island of Roses certainly reflects some of this longstanding self-consciousness, his desire to recuperate the Sephardic tradition of including rue in the berit mila ceremony represents a new generation of Sephardic Jews. In a world that, in many ways, attempts to value and understand multiculturalism, Sepharadim may be inspired to reintroduce their traditions back into the portrait of modern Judaism.