Levaya i Bedahey: Processions and the Life Cycle in the Cemetery

Summary:

- In the former Ottoman Empire, and even in the United States, Sephardic funerals were multigenerational.

- Special processionals and services were reserved for rabbis and religious leaders.

- The cemetery, known in the Ladino as the bedahey, was an important instutition in Sephardic communities.

A biblical funeral sets the stage for how Sepharadim honor the deceased

The first funeral processional described in the Hebrew Bible, in the book of Genesis, focuses on Ya’akov — the patriarch Jacob and the progenitor of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Channeling generations of biblical commentary, the Me-am Lo’ez, a Ladino biblical commentary and encyclopedic source of Sephardic customs, paints a striking visual of this elaborate processional, emphasizing how both Jews and Egyptians alike paid their respects:

I el aron era de oro kon piedras presiozas i kovechado kon vestas de reynado. I una korona grande en su kavesera i los shevatim ivan kargando el aron segun el seder ke avizemos ariva i toda la djente de Mitsrayim bien vestidos i ermados ivan kaminando adelantre yorando i endichando...I sinkuenta esklavos ivan i vinian entre la levaya arochando a la djente modos de golores i almeskale i aziendo lugar para ke puedan kaminar la djente ke no se pezen una el otro…

"And [Jacob’s] coffin was made of gold, encrusted with precious jewels and covered with royal vestments. And on the head of the coffin was a large crown, and the tribes [Jacob’s sons] carried the coffin in the order described above, and all the Egyptian people walked, wearing their best clothes, crying and mourning....And fifty servants joined the processional, carrying all sorts of perfumes, and they also kept space open so that the people could walk without pressing one against the other."

What does this commentary teach about Sephardic funerals?

It is clear in the biblical text that Ya'akov developed positive relationships with his neighbors. What the Me-am Lo'ez injects into the story here is the level of cultural integration between Jews and Egyptians in the ancient Near East. While it is often difficult to glean historical reality from biblical commentary, the story in Genesis, as described by the Me-am Lo'ez, may offer modern readers a context for understanding the multicultural and intergenerational funeral processions that took place among Sephardic Jews throughout the Ottoman world of which the authors of the Me-am Lo'ez were a part.

In the Ottoman Empire, funerals were multicultural

Jews in the Ottoman Empire into the twentieth century patterned their funerary practices on the biblical model enhanced by cross-cultural dialogue with their Muslim neighbors.

As a Jew growing up in Salonica, a culturally diverse city home to Jews, Muslims, and Christians before the Holocaust, David Perahia observed the uncanny similarities between Muslim and Jewish funerals — especially the processionals.

According to Perahia, Salonica’s Muslims would follow the hearse with food to the cemetery as onlookers threw candy and coins as the processional passed — a tradition that Perahia notes was enthralling for the local children.

Rabbi Solomon Azose, the first rabbi of Sephardic Bikur Holim congregation in Seattle, which is still operational today. Click to enlarge.

Funerals were also intergenerational

Jewish funeral processions for wealthy individuals in Salonica were similarly elaborate with up to twelve rabbis behind the coffin, followed by flowers, musicians, and a children’s choir — an elaborate scene reminiscent of Ya’akov’s grand processional in the Bible. Consistent with the kortar mortaja and the bet ha-hayim, Perahia’s account also shows that Muslim and Jewish communities did not shield children from death.

Honoring religious leaders was of supreme importance

In Seattle, the processionals for rabbis made indelible impressions on the young people who witnessed them. Even in their seventies and eighties, community members recall these processionals in detail.

In an oral history interview, Solomon “Mo” Azose illustrates the grand processional for his grandfather and namesake, Rabbi Solomon Azose, that traversed nine miles from the Central District to the northern outskirts of the city:

SOLOMON AZOSE: My grandfather died in 1919. He was only here for about 10 years...at that time the cemetery was out on 102nd and Aurora where the old cemetery is there. And there was [sic] 40 cars going out there and you can imagine, in 1919, roads were really scarce. The cars were not that great. 40 cars — he must have been pretty popular here in Seattle.

Similarly, when Rabbi Avraham Maimon passed away in 1924, there was also a major processional with other striking visual elements. Elazar Behar recalls the funeral, which he witnessed as a child in Seattle:

ELAZAR BEHAR: It was early Saturday morning when Yitshak Yisrael came by the synagogue — he used to come very early. He lived one block from Rabbi Maimon at that time who lived on 17th and what’s now East Alder. And he told my dad that he thought the rabbi had died—that Hakham Maimon had died...My dad had brought the children down from our Talmud Torah and he had lined them up in the street and he gave them each a candle with a black ribbon on it. And when the funeral was going to start the men came by, and, like they did in the old country, they took the casket from the house, put it on their shoulders and they marched singing certain songs...We went up to 19th avenue, down 19th avenue to Fir Street, and up Fir Street a half a block to the then being built — not completed — Bikur Cholim that was on 20th and East Fir, on Fir Street.

Behar recalls that his father interrupted a school day in the Sephardic Talmud Torah (religious school) to not only encourage young students to attend Rabbi Maimon’s funeral, but to actively participate.

The cemetery was an important institution for the living Sephardic community

The obituary for Rabbi Avraham Maimon in La vara, the most important Ladino newspaper in the United States. Click to enlarge.

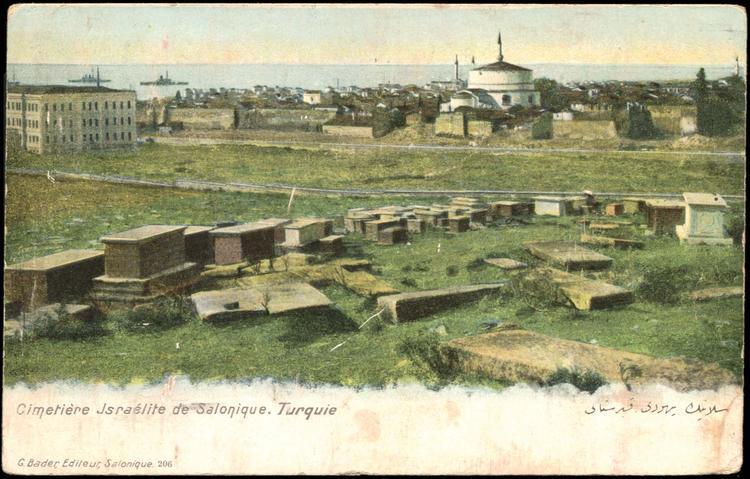

Just like the funeral processionals were multigenerational, so too the cemetery itself was a place where generations often intersected. In Ladino, the cemetery was known as the bedahey, a Ladino variation of the Hebrew bet ha-hayim, meaning "house of life." Instead of symbolizing fear, sickness, or bad omens, it was a place to pray for new life, hope for success, and a testament to a community’s vitality. Children, even in their old age, would visit their parents’ graves to share their problems and worries, “in the same manner as had been done in life.” Pregnant women across the Ottoman Empire would also go to the cemetery close to giving birth to pray for a healthy child — a practice that brought the two extreme points of the life cycle together.

Sephardic Jews made annual cemetery pilgrimages known as ziyara to visit the graves of loved ones — a variation of the Arabic word ziare, meaning to visit, and a custom inspired by their Muslim neighbors dating back to pre-Inquisition Spain. They also prayed at the graves of famous rabbis before Rosh Ha-Shana (the Jewish New Year) and Passover, and, in Salonica, a communal ziyara grande (great pilgrimage) took place before the Jewish New Year.

Today in the United States in Sephardic communities like Seattle, a similar ziyara grande takes place: Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation (founded primarily by Jews from Turkey) makes the ziyara on the Sunday between Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur; Congregation Ezra Bessaroth (founded primarily by Jews from the Island of Rhodes) makes the pilgrimage twice: once before the beginning of the month of Tishri (the same month during which Rosh HaShana falls out), and once before the beginning of the month of Nisan (the month during which Passover occurs).

The cemeteries also offered niche employment opportunities. Honadjis, a Turkish-dervied term literally meaning “callers,” were rabbis of lower status who escorted visitors to specific tombs and recited prayers. Sometimes, for a funeral, families would also hire planyaderas—professional mourners who would cry, sing mournful dirges, and recite elegies with musical accompaniment.

The circle of life -- in the cemetery

The multigenerational engagement among Sepharadim at the “end” of the life cycle —both in the Ottoman Empire and in Seattle — tangibly illustrates that the life cycle is, indeed, a cycle: A continuous sequence where beginning and end overlap. With the cemetery central to many Sephardic communities, it became a living institution, and Sepharadim were raised to engage and confront the life cycle at every phase.