Kortar Fashadura: A Sephardic Baby Shower

Summary:

- While popular Jewish discourse suggests that Jews don't have baby showers, Sephardic women have been hosting baby showers for centuries.

- This celebration is known in Ladino as a kortar fashadura.

- At a kortar fashadura, women sewed clothes for the newborn and sang Ladino songs known as kantikas.

- These kantikas were preserved in a song book and organized by musical mode known as makam.

- This festive celebration was linked with another life cycle celebration before death known as the kortar mortaja.

Do Jews have baby showers?

As American mothers-to-be in the 1940s began to celebrate the first modern-day baby showers, igniting a trend that is widespread today, did Jewish women also participate? Perhaps not: Jewish blogs and online forums — even American rabbis — attest today that “Jews don’t have baby showers.” A baby shower, they say, may provoke the evil eye, or in Hebrew, ayin ha-ra, (and in Ladino, ojo malo or ayinara), which could bring harm to the mother and her unborn child.

But a custom popular among Sepharadim challenges this assumption and suggests that over the generations Jews did celebrate a baby shower of sorts. A gathering known as kortar fashadura (cutting the swaddling cloth) was common throughout the Ottoman Empire and was primarily preserved through the unique ballads sung at this festive occassion.

What happened at a kortar fashadura?

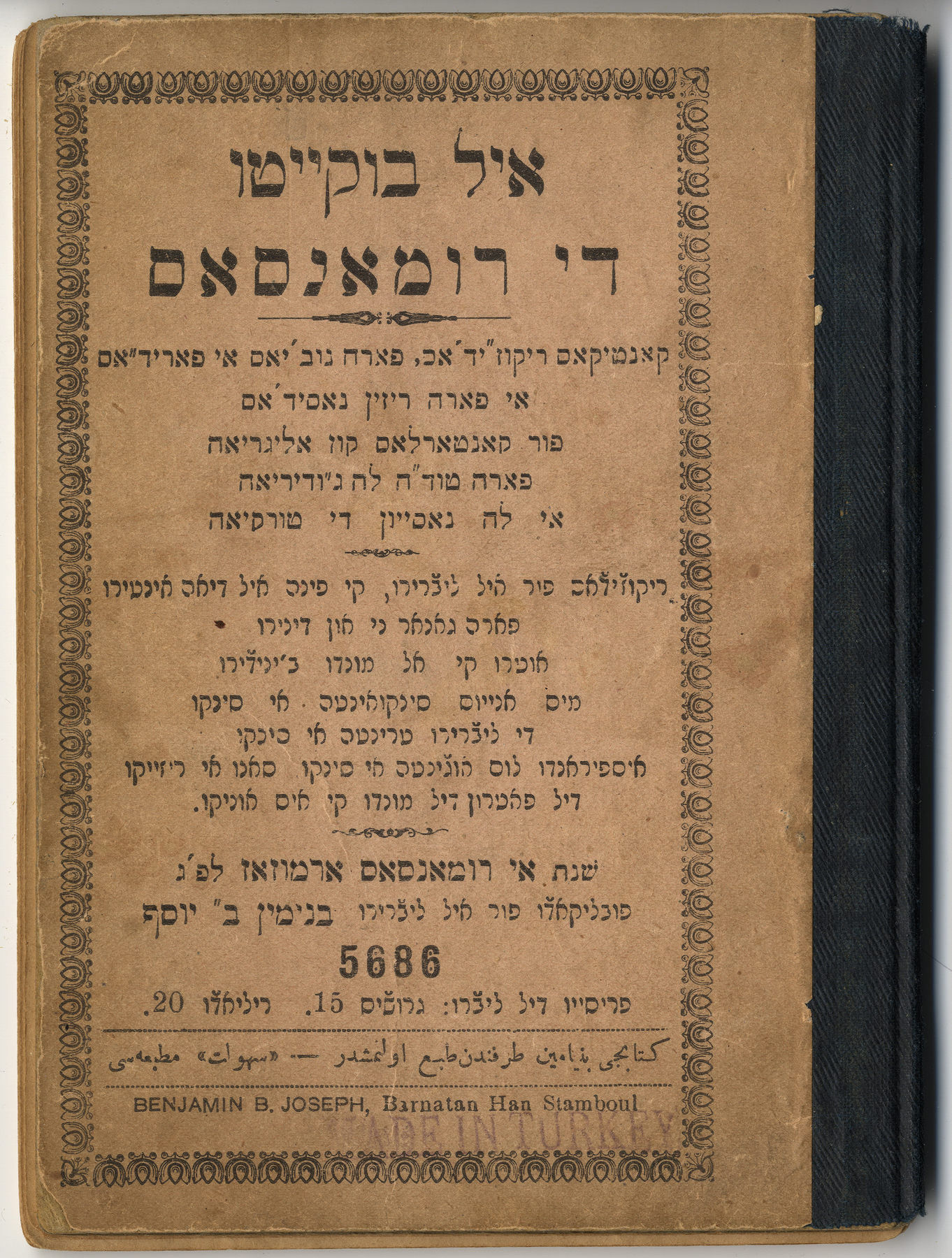

Title page of El bukyeto de romansas (Istanbul, 1926), a Ladino song book that includes kantikas for brides and new mothers. Click to enlarge.

The kortar fashadura was a festive environment: The primary activity at the celebration was to sew the newborn clothes, which eventually amounted to an elaborate layette. As women stitched and created together, they also sang — from memory — Ladino songs, or kantikas, about childbirth and love.

Much like baby showers today, the kortar fashadura was held in the home and usually only attended by women. It was one of many celebrations associated with childbirth among the diverse communities in the Ottoman Empire, such as the babinden, a festival in honor of midwives practiced by Bulgarian Orthodox Christians, and the aqiqah, a feast held seven days after a baby is born in Islamic communities.

Preserving the kortar fashadura in a song book

As political, cultural, and demographic transformations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century began to erode traditional practices like the kortar fashadura, community leaders published the lyrics of the oral songs so that they would continue to be used and preserved for posterity. One such booklet, called El bukyeto de romansas, (published in Istanbul in 1926), collects 32 songs to be sung for brides and new mothers — a sign of the traditional expectations placed upon women.

Popular Ladino songs for new mothers

Although this edition of El bukyeto de romansas was published in Istanbul, some of the songs within its collection were widespread throughout the Sephardic world. One is the evocative song for new mothers titled Kantika de la parida, (“The Song of the Pregnant Woman”), also known as Och ke mueve mezes (“Oh, These Nine Months”), which was ubiquitious from Salonica to Monastir to Istanbul. The lyrics carry a celebratory tone, and there is no mention of the evil eye, or any reference to anxieties surrounding pregnancy and childbirth.

The kantika’s refrain, which refers to the child ultimately being born, triumphantly declares: Ya es buen siman, este alegria, bendicho el ke mos ayego a ver este dia! (“This is a good sign, this happiness, blessed be the one who brought us to see this day!”) The refrain also carries an allusion to the end of the Ladino translation of the shehehiyanu blessing, which is recited to welcome in new experiences: i nos ayego a el tiempo el este (“Blessed is God that we arrived to this time”).

The most famous song included in El bukyeto de romansas is Avraham Avinu, a Ladino standard today that few realize describes the birth and circumcision of the biblical figure, Isaac — hence its inclusion in the collection.

To read a translation of one song from El bukyeto de romansas, click here.

What did these songs sound like?

The pages of El bukyeto de romansas do not look like a song book many of us may be used to seeing: No musical notation in the western style accompanies any of the lyrics in the collection. Instead, the appropriate makam, a Middle Eastern musical mode popular in the Ottoman Empire — and among Jews, as well — is identified for each song. If you know the makam, you know how to sing the song. The musical style is a profound reminder of the ways in which Sephardic Jews were deeply embedded in their Ottoman context, even for intimate celebrations relating to childbearing and parenthood.

Listen to "Song of the Pregnant Woman" Kantika de la parida by Hazzan Isaac Azose

The kortar fashadura was closely linked to another Sephardic life cycle custom

The kortar fashadura was not the only time in which Sephardic communities gathered to sing and sew life cycle garments. Another celebration bookended the kortar fashadura at the end of one's life: the kortar mortaja.

What is the kortar mortaja?

Although preparing burial shrouds in advance of one’s death was a widespread Jewish custom, Sephardic Jews approached the preparations with a unique sense of joy and community. The kortar mortaja — literally translated as "cutting the burial shroud" — was a celebration in which a person would be fitted for their burial garments. In Hebrew this outfit is known as takhrikhim, derived from the word “to wrap," and consists of a tunic, hood, pants, and belt.

What is the source of this practice, and why was it done?

The practice of preparing the shrouds before death is alluded to in the Me-am Lo’ez, a Ladino commentary on the Bible and encyclopedia of Sephardic customs:

I muncha djente ke apontan en el Djudezmo tienen su mortaja pronta ke se la azen en su vida i es muy bueno por munchas sibot i una de eyas es kisas se muerira dia de mo'ed i sera hekhreh de azerla por mano de goyim i vestido del otro mundo no konviene ke se koza por manos enkonadas.

"And many people point out that in Judaism they have the shroud prepared promptly while they are alive, and this is very good for many reasons, and one is that one may die on a festival, and then they will be forced to have [the shrouds] made by the hands of non-Jews, and the clothes of the next world should not be made by fervent hands."

The primary reason for preparing the shrouds in advance, according to the Me-am Lo’ez, is so that the garment is prepared by Jews — in other words, by one’s own community.

Instead of life and death existing in stark opposition, the kortar mortaja rendered the emotional boundaries between beginning and end more fluid with its joyous tone.

The fasha and the mortaja were created in social settings at home with family and community. What is important in Sephardic tradition is not the place you wind up — the cradle or the grave — but rather what is embracing you: the fasha and the mortaja. These two garments initiate the beginning and the end of life and render both of these events communal rather than solitary experiences.