Meldado: Jewish Memorial Services and the Boundaries of Sacred Space

Summary

- Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews both hold memorial services for the deceased: Among Ladino-speaking Sepharadim the service is called a meldado; among Ashkenazim it is known as a yahrzeit.

- Some Sepharadim also call the memorial service a yahrzeit.

- A meldado service includes reading from a selection of Jewish texts and partaking in a communal meal.

- Historically, a meldado took place in the home; by the twentieth century, most services were held in the synagogue.

Yiddish among Ladino

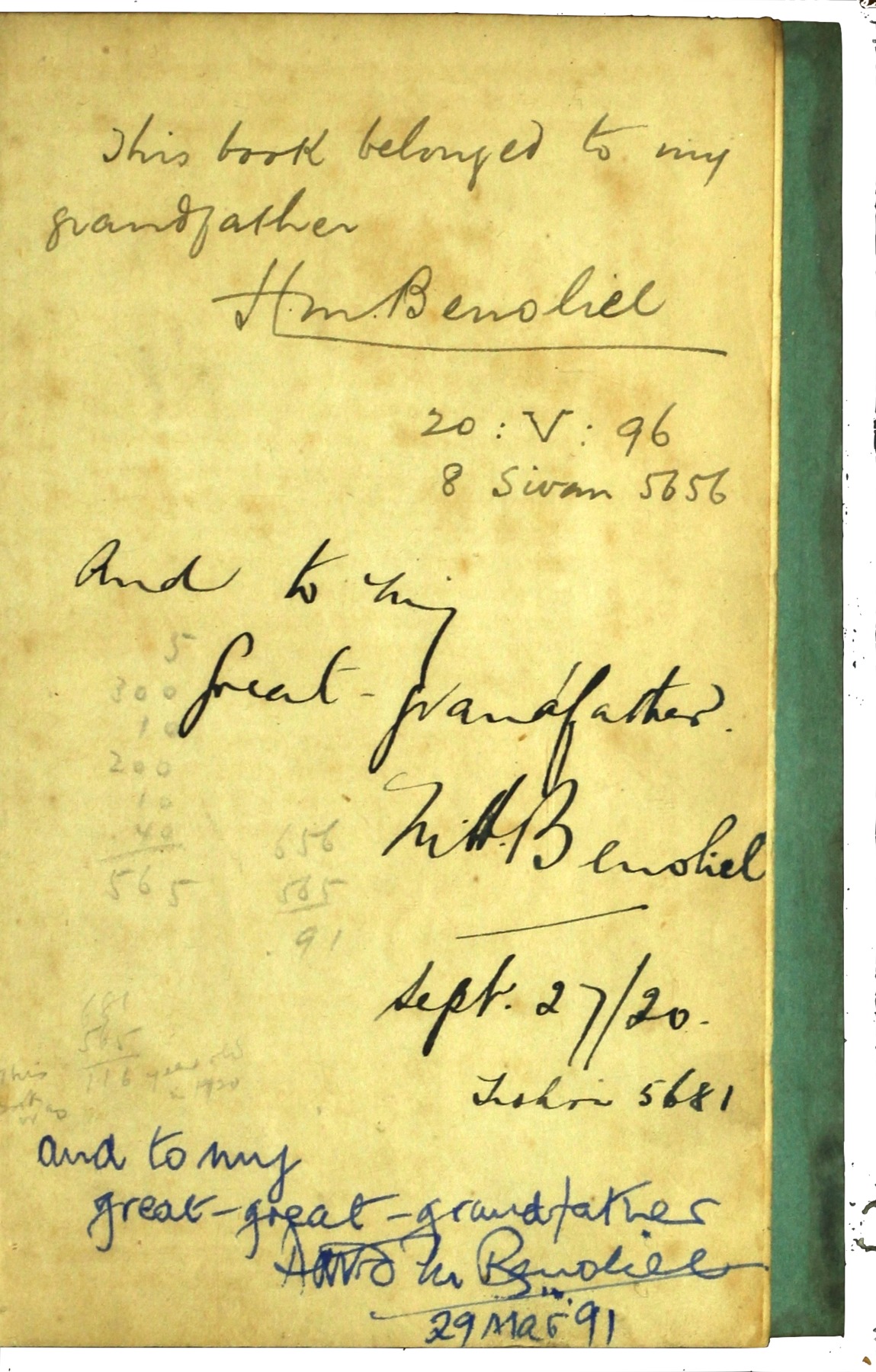

Inside cover of a Benoliel family prayer book inscribed with family birth and death dates. Click to enlarge.

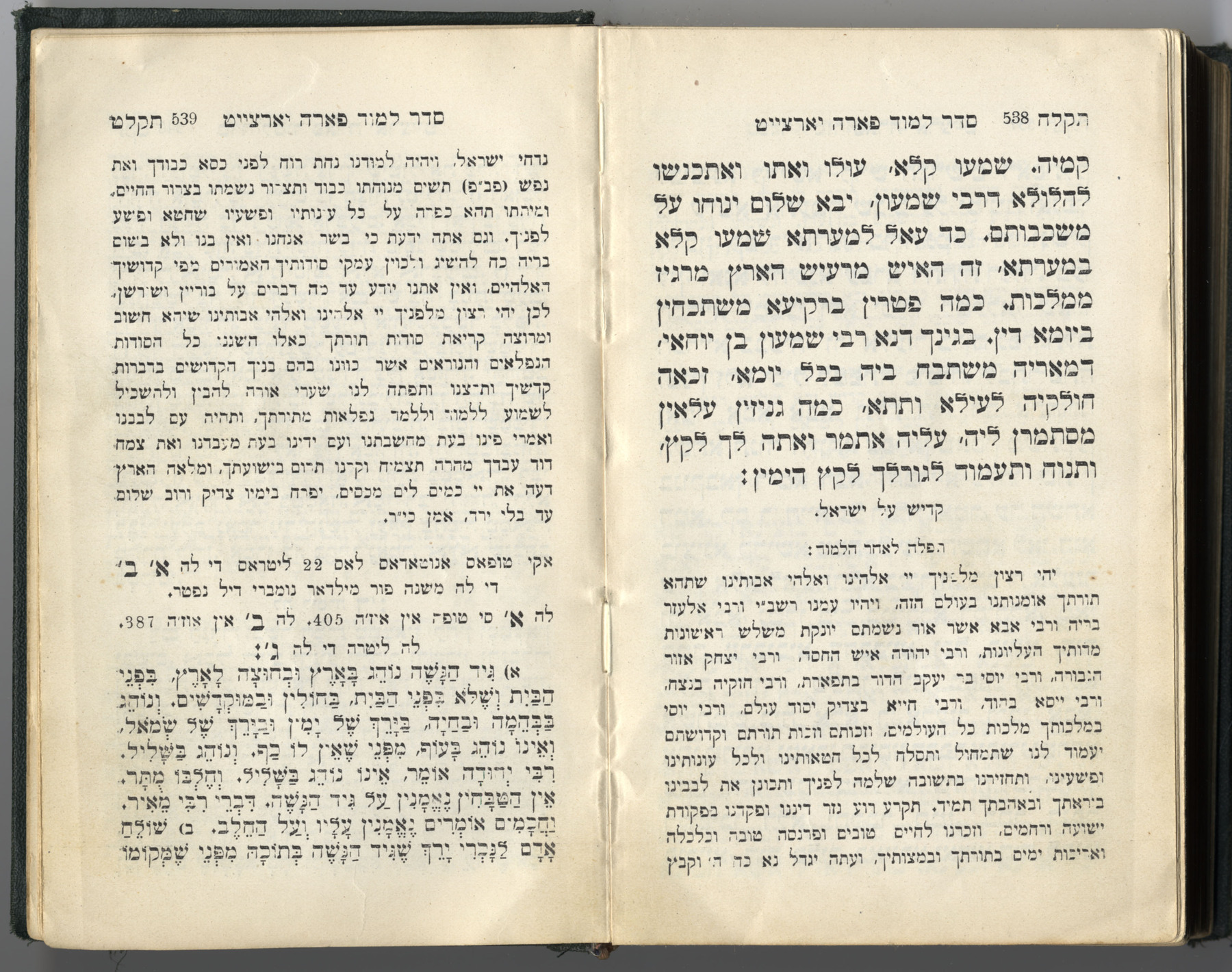

Sefer Keri’e Mo’ed, a siddur (prayer book) used for the Jewish holidays, has been in Al Benoliel’s family for generations. It traversed continents as the family moved between Gibraltar, Morocco, Manchester, and finally, Seattle, where Al shared the book with the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. But you don’t have to take Al's word for it: the book speaks for itself. On the inside front cover of the siddur, published in 1803, each member of the Benoliel family who has used this prayer book inscribed their names and relationship to the previous owner, and recorded their date of passing.

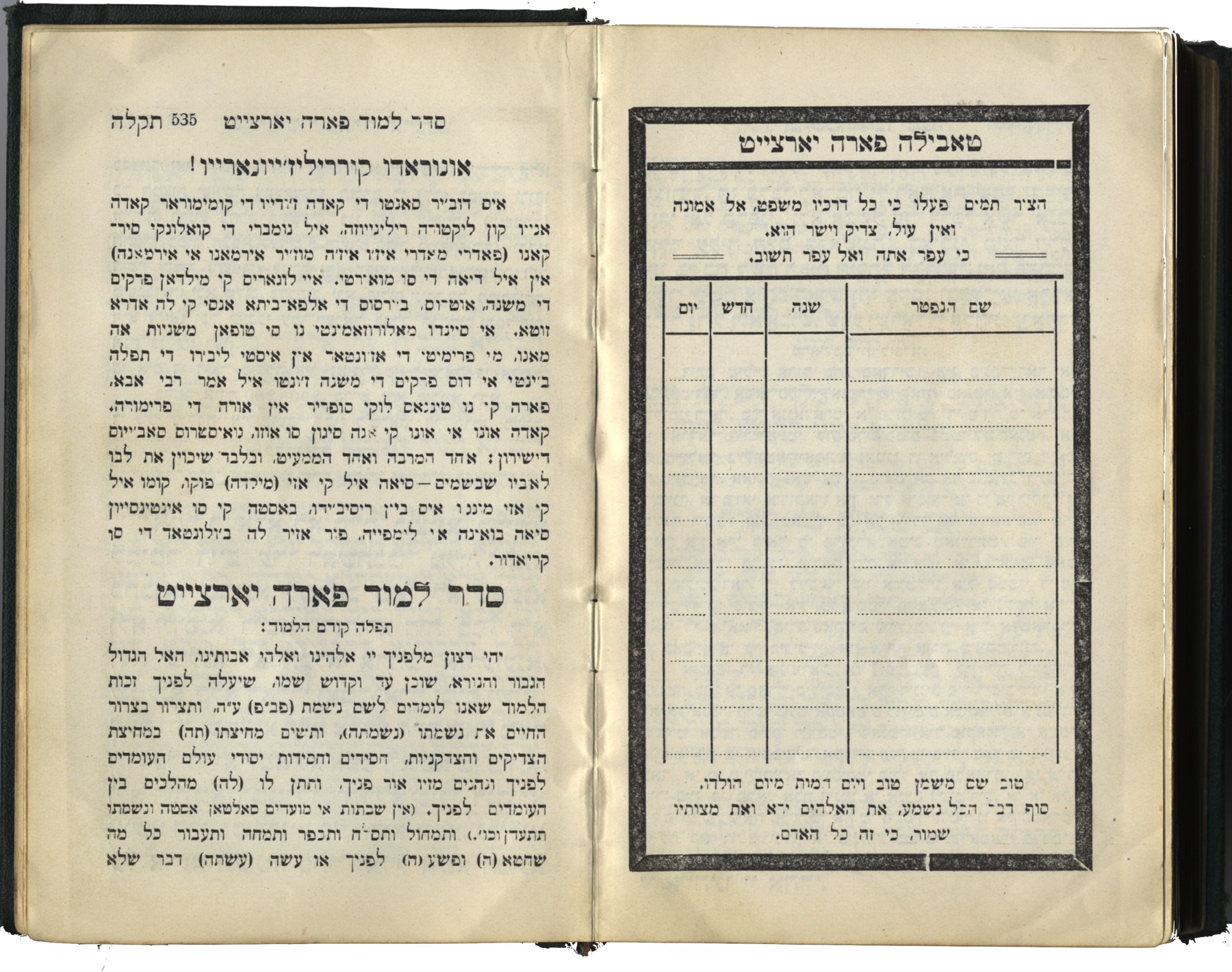

Using pages of prayer books (and bibles) as a place for keeping a record of family life cycles is somewhat of a Sephardic tradition in and of itself. In the twentieth century, Jewish printers apparently became aware of this recordkeeping practice and began including ready-made tables in prayer books that could be filled in with death anniversaries.

But Sephardic prayer books with Ladino translations often call these tables Tabula para yahrzeit ("the table for the yahrzeit”) introducing a distinctly Yiddish phrase into the otherwise Ladino heading. Apparently, the Ladino-speaking readers would understand this Yiddish phrase — but how? How did the Yiddish word yahrzeit make its way into Ladino? Why do these tables not use the Ladino word for memorial service: meldado?

What is a meldado?

In Ladino, a meldado (or anyo) is a commemorative date to mark the anniversary of a person's passing. It is derived from the Ladino word meldar, meaning “to read,” or “to study,” which relates to the practice of reading passages from various Jewish texts on the anniversary of a person’s burial.

What is a yahrzeit?

In Yiddish, yahrzeit, which literally means “time of year,” also refers to the anniversary of a person’s passing. As the name suggests, a formal yahrzeit is only observed once per year and is often commemorated by lighting a memorial candle and reciting the kadish, an Aramaic prayer that was originally recited upon completing a major Jewish text. The kadish was formulated for mourners for the first time in the thirteenth century in Vienna.

Sepharadim and Ashkenazim share some memorial customs

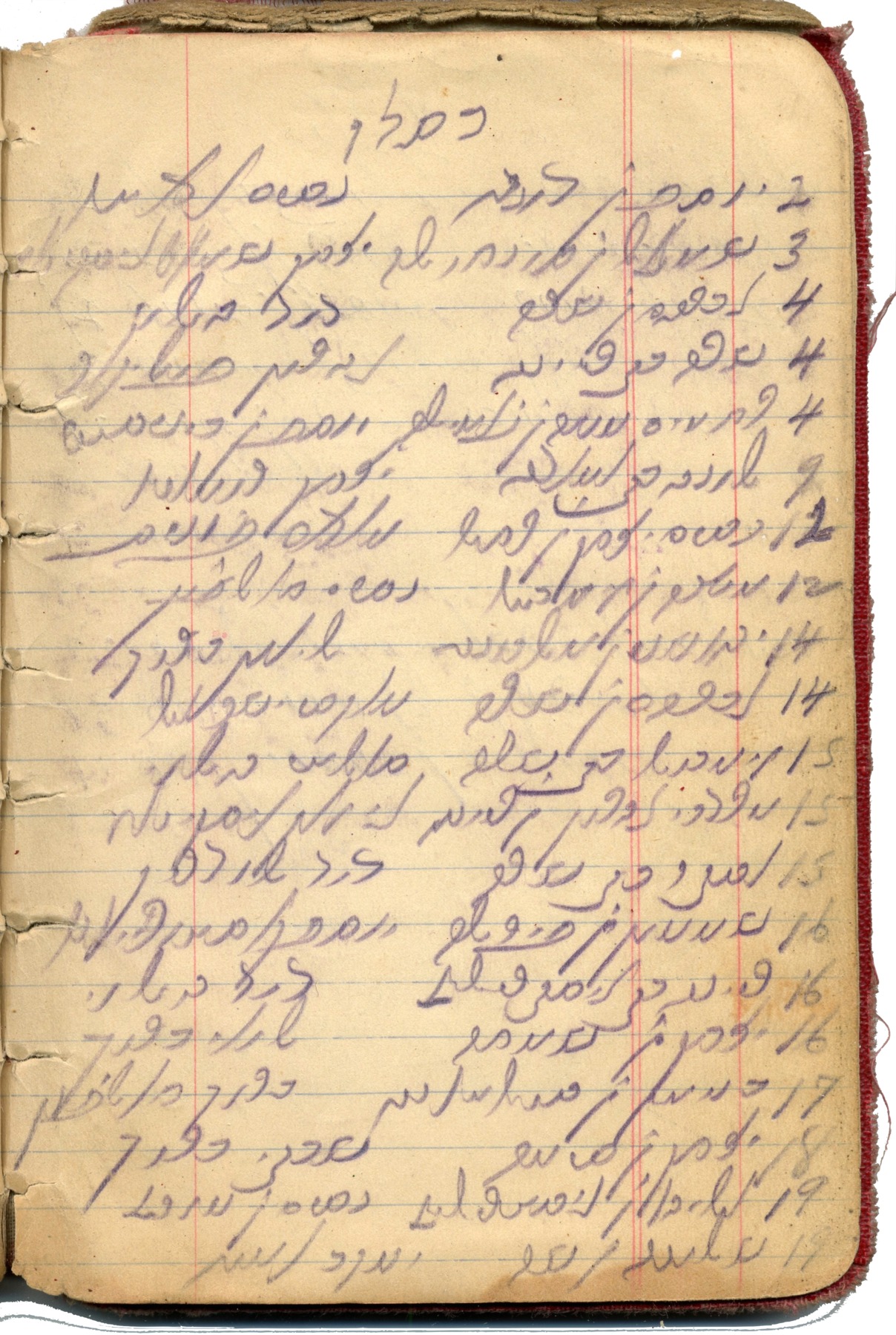

Notebook of meldados in the Seattle Sephardic community kept by Rev. Morris Scharhon, rabbi of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, written in soletreo (Sephardic Hebrew cursive). Click to enlarge.

In the first year after a person’s passing, a meldado may be observed up to six times. Jewish law dictates a specific cycle for mourning beginning with shiva, or los siete, the seven day period following burial observed by Ashkenazim and Sepharadim alike during which many Jews will stay home and receive visitors while sitting on the floor — a sign that they are grieving.

Other customs are unique to Sepharadim

Sepharadim observe a unique custom on the first day of the siete known as the seudat havra’a, the meal of consolation. According to the Sephardic tradition, the seudat havra’a must be prepared by family or friends; the mourner cannot prepare the food on his own. Shem Tov Gaguine, author of the Keter Shem Tov, an explanatory work on Sephardic customs and practices, explains that having others prepare the seduat havra’a forges deep bonds between community members — a bond that would be rendered even more intimate by hosting the meal at home.1

The seudat havra'a included symbolic foods that related to the life cycle. Panezikos (sweet rolls), huevos haminados (hard boiled eggs), olives, and raisins — all round — represented the circle of life. The raisins carried an additional significance: known in Ladino as pasas, raisins are a word play on the similar Ladino word pasar found in the phrase i esto va pasar ("this, too, shall pass")2 an adage of Persian origin that likely entered Ladino through Ottoman Turkish and only entered English in the nineteenth century.

Following the siete, Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions continue to diverge. After thirty days (known as korte de sheloshim or korte de mes in Ladino), Sepharadim continue to hold a meldado after seven months, nine months, eleven months, and one year (el anyo). Ashkenazim also observe the annual anniversary with a yahrtzeit service, but not the other dates in between.

With such different traditions, how did a Yiddish word make its way into Ladino?

Nonethless, the fact that yahrzeit was so commonly used by Ladino-speaking Sepharadim, as evidenced by its inclusion in the Ladino prayer books, is a nod to just one of the several cultural exchanges between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. Gaguine notes the use of yahrzeit among Ladino speakers and even references siddurim like the ones shown above as evidence for the word’s ubiquity among Sepharadim. He reminds readers that there were Ashkenazi populations in cities like Izmir, Istanbul, and Bulgaria, and that Sepharadim and Ashkenazim lived side by side — and that their languages intersected.3

To add to Gaguine's observation, the inclusion of a Yiddish word into Ladino may point to the importance of memory in the Jewish tradition that transcends the boundaries of language and culture.

What happens at a meldado?

As previously mentioned, the word meldado is derived from the Ladino word meaning "to read" or "to study," which references the centerpiece of the Sephardic memorial: reading from a selection of Jewish texts. Some of the of text is sourced from the biblical Book of Psalms, organized alphabetically and known in a collection as the Alpha Beta. The mourners then create an acrostic using the name of the deceased.

Additionally, selections from the Mishna, the first written record of the Jewish oral law and the most foundational work of rabbinic literature, are read according to the same acrostic system. These selections record ancient legal arguments and make no mention of death or the act of memorial. The mishnayot are, however, opaquely connected to remembering the deceased: the Hebrew words Mishna and neshama — which means “soul” — have the same numerical value (gematria).

Where did a meldado take place?

In the Ottoman Empire — and for a short period in the United States, as well — meldados were always held in family homes. Before meldado became synonymous with memorial services, the term simply referred to a study session. At these gatherings, people came together not to study a text deeply and acquire new knowledge, but rather to engage in the performative act of collectively reading a sacred text -- much like people do at meldado memorial services today with the prescribed readings mentioned above.

A meldado made the home a sacred space

The association of meldado with memorial services may relate to a desire to elevate, direct -- and ultimately restrict -- a communal gathering to one purpose: ritual memory. The exact origins of the meldado study session in general are unknown, but the notion of reading as a performative act is likely rooted in Jewish mystical tradition, or kabbalah, a branch of Jewish thought that had a particularly strong influence on the Sephardic world. According to kabbalah, the mere act of reading a Jewish text, even without comprehending it fully, has the power to serve as a form of ritual repentance, or teshuva, for the readers in a study group. While the earliest recorded study sessions among Sepharadim utilized compilations of Hebrew texts (the most popular collection being the book Hok le-Yisrael), by the ninetheenth century, rabbis in the Ottoman Empire were strongly encouraging meldados that relied on Ladino rabbinic literature as the centerpiece.

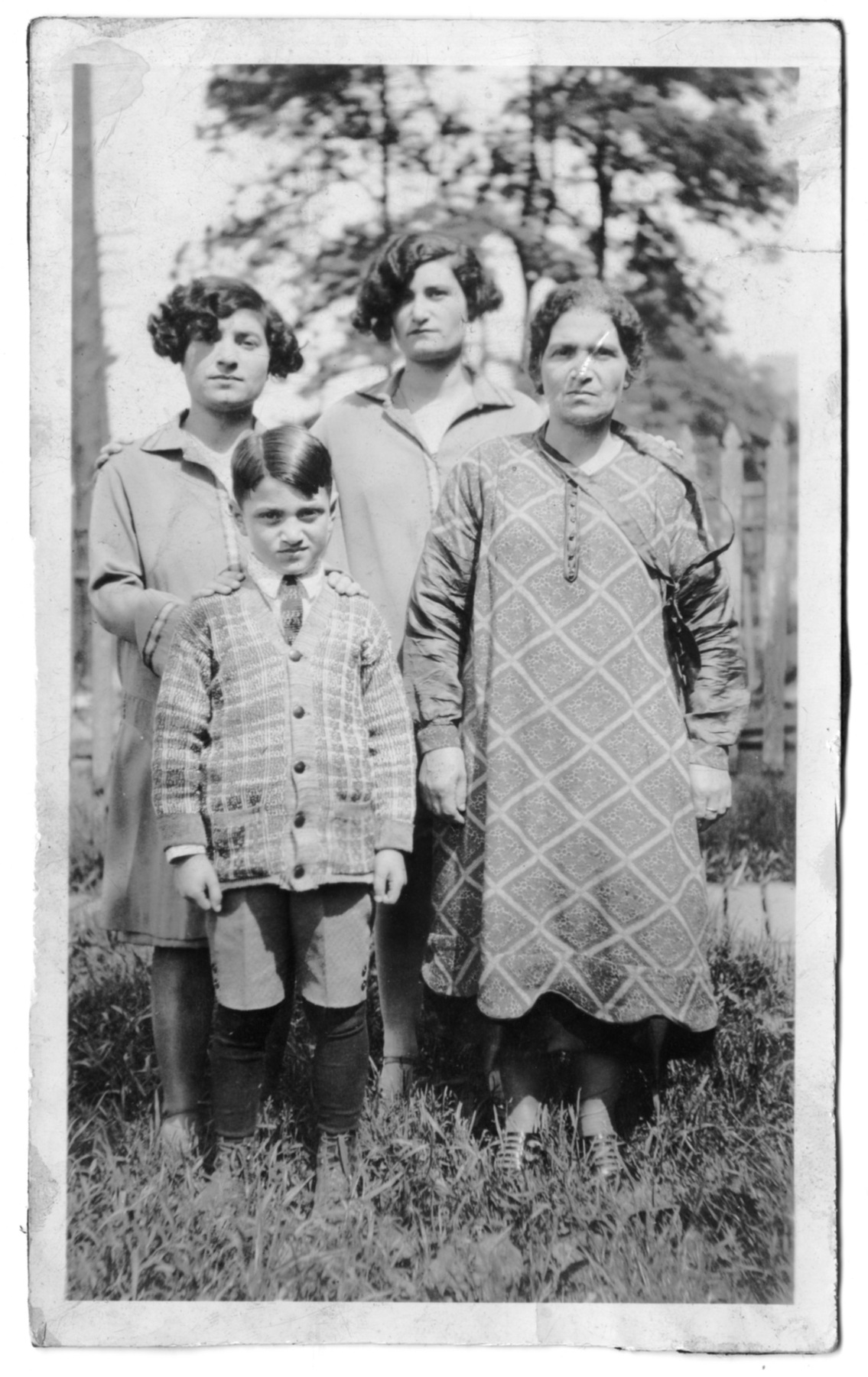

Louse Azose (née Maimon), right in plaid dress, pictured with her mother, Vida Sultana Maimon (center), sister Fanny (left), and brother, Rabbi Solomon Maimon, in Seattle.

These nineteenth-century Ottoman rabbis also attempted to wield the meldado as a way to sanctify the home and control the kinds of social interactions that took place there, and their writings often portray home as an ambiguous zone: Men and women may dance together, play too much tavla (backgammon), or drink too much raki (anise-flavored liquor) -- all activities frowned upon by traditional rabbinic authorities. For the rabbis, one way to sanctify the home and elevate it to the level of a synagogue -- where social interactions were controlled and appropriate -- was to introduce the ritual act of reading into the private sphere.4

With time, this attempt to restrict the nature of social gatherings via the meldado actually had a somewhat different effect: instead of drawing hard lines between sacred and profane -- between synagogue and non-synagogue spaces -- the meldado uniquely contributed to the Sephardic conception of sacred space. Sanctity could be fashioned by anyone, anywhere. Ritual observance was diffused throughout the community, and the home could become its own synagogue of sorts for the right occasion. As we have seen, these occasions that brought holiness home were often life cycle events, such as a kortar fashadura (Sephardic baby shower) or fijola (baby naming).

In the United States, the meldado changed

The fluid conception of sacred space among Sepharadim did not last. As a result of the rupture provoked by immigration to the United States in the twentieth century, and the American Jewish notion that the synagogue was the prime space of Jewish life, younger Sepharadim begun holding meldados in synagogues.

But some individuals in Seattle, like Louis Azose — mother to Isaac Azose, hazzan (cantor) emeritus of Ezra Bessaroth in Seattle — had grown up with meldados held exclusively in the home and regretted the change, as recounted in an interview in 2000 conducted by Sephardic studies scholar Aviva Ben-Ur:

AVIVA BEN UR: Did you come especially for the meldado? Do you do that every year?

SELMA FRIEDMAN [Louise’s daughter]: No. Ike [my brother] usually handles it for my mom, or my brother Mike from Chicago — Mike is a rabbi. And neither one was able to come and be there for mom. And I know how much it means to her to have the meldado in the house as opposed to having it in the kahal [synagogue]. So I told her about a month ago that I would come and help her.

BEN UR: Why don’t you like it [the meldado] in the synagogue?

LOUISE AZOSE: They come, they say a few words as a meldado, boom, everybody goes home. I never did like it. Never. I mean, not my meldados. It's been always at home. Always. Another meldado that I go, they just sit for five minutes and boom — they go. They make the meldado and they go.

BEN UR: And there is no meal, no mishnayot?

AZOSE: Nothing. No. Mishnayot yes, they do. But just — poof! Everybody goes — to their houses, you know.

As Azose notes, the primary custom lost in the shift from meldados at home to meldados in synagogue was that of the communal meal. Meldados held at synagogue focused on reading and learning and lost the casual community atmosphere that came with eating together. Azoses comments bemoan the loss of the communal meal as a time to not only remember, but also to celebrate — an attitude fundamental to the Sephardic conception of death, burial, and memory.

Despite its changes, the message of the meldado remains

Even as Sepharadim began to observe meldados in synagogue, they were always observed together. The collective experience of remembering as a community is the essence of the meldado, and it closes the life cycle just as it began. Before a person is even born, they are part of a community: the kortar fashadura is a celebration that initiates someone into the group before they are even aware that they belong to one. Even after an individual passes away, the community carries their memory through the meldado. From the cradle to the grave — and even before and beyond — Sepharadim joined together to celebrate the most monumental times in a person’s life.

References:

1. Gaguine, Shem Tov. Keter Shem Tov. Ramsgate, England, 1934. Reprint, Jerusalem: Israel, 1998. pg. 781, section 807:

טעם שסעודת ההבראה צריכה להיות משכניו ולא משלו וטעם הדבר דכי לקרב הלבבות בינו ובין שכניו, או קרוביו ומידועיו, שכשרואה האבל מביא לו לחם ובצים ויין יגדל אהבתם וחיבתם ביניהם

2. Scharhon, Morris. Alan Scharhon, ed. A Time to Weep: A Guide to Bereavement Based on the Customs of the Seattle Sephardic Community. Seattle. pg. 68

3. Gaguine, Shem Tov. Keter Shem Tov. Ramsgate, England, 1934. Reprint, Jerusalem: Israel, 1998. pg. 168, Section 311:

ומענין לדעת שרבני הספרדים בארץ ישראל ובטורקיא האחרונים תמצא בספריהם שבמקום להזכיר יום הפטירה כמנהג הקודם, משתמשים במילת יאהרצייט כהאשכנזים, כנראה שלמן היום שבאו אחינו האשכנזים ונתישבו בארץ ישראל, ובקושטא, ובאיזמר, ובולגאריא וגו׳ למדו הביטוי הזה מהאשכנזים ונסתפרדה המלה הזאת

4. Lehmann, Matthais B. Ladino Rabbinic Literature and Ottoman Sephardic Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.