Kombidadores: Sephardic Wedding Invitations and Social Change

Summary:

- Before printed wedding invitations, Sephardic communities relied on an individual known as the kombidador: the invitor. In Seattle, the kombidador for many years was Avram Barlia.

- The kombidador's role was imbued with religious significance: Attending a wedding as a guest fulfills a Jewish obligation to make the bride and groom happy on their wedding day.

- By the 1920s, printed wedding invitations were becoming more popular and the role of kombidador became less relevant.

- Printed wedding invitations also signified major shifts in the prevalence of the Ladino language among Sepharadim in the United States.

Archives show us how much the world has changed — but they also illustrate that elements of the human condition persist despite shifting cultural trends. Our archive has taught us that most people want to remember their weddings, and they will save invitations, telegrams, and photos for years to recall this special day.

The wedding invitations in the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection carry multilayered messages. Of course, they celebrate and commemorate one of the most joyous occasions in Jewish life. They also illustrate major changes in the social fabric of Sephardic communities across the world, including in Seattle.

Announcing a wedding before printed invitations: The kombidador

Before the elaborate printed wedding invitations we open today, and before the colorful evites we receive in our email inboxes, there was the kombidador. Until the twentieth century, the kombidador was a unique and now long forgotten position within Sephardic communities throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Derived from the Ladino word kombidar, “to invite,” the kombidador (or female kombidadera) was responsible for personally inviting guests to celebrations within their specific communities, especially weddings. Well-acquainted with their surrounding neighborhoods, the kombidador would receive a guest list from each family and begin marching through the streets, loudly announcing the upcoming festivities to all the invitees at their homes.

Avram Barlia, the Seattle kombidador

Even once printed wedding invitations came into fashion beginning in the nineteenth century, along with the introduction of the postal service, the kombidador preserved his status as an integral component of community celebrations well into the twentieth century — even in places more than five thousand miles away from Turkey and Greece, such as Seattle.

Fortuna Calvo, the first Sephardic child born in Seattle, recalls a man by the name of Avram Barlia who served as Seattle’s kombidador for many years. Some also remembered him as the shamash, or synagogue assistant:

FANNIE ROBERTS: What kind of social life did you have a child?

FORTUNA CALVO: We had quite a social life. Not any planned socializing, but the women did get together quite often. There was a lot of good times held on a Sunday night, I think. That’s the night that they played fijanes [game played with coffee cups]. They had a little baking. They used to have vijitas [receptions] in the daytime -- I remember that -- commemorating engagements or a new baby. There was a vijita was called and everybody went and visited.

ROBERTS: How were people invited?

CALVO: By Mr. Barlia.

ROBERTS: Who was Mr. Barlia?

CALVO: Mr. Barlia was our “shamas” [sexton]. He used to go to each house, and invite everybody. At times of weddings, where engagements were announced, Mr. Barlia was the one who carried the sweet trays. He carried it from the groom’s to the bride’s home, with all the goodies.

ROBERTS: You mean the mandada [bride and groom’s gifts to each other]?

CALVO: Yes, He carried it there. Of course, then it was the time that the bride’s mother called the whole city, and they had a vijita.1

Why was the kombidador so important?

As Calvo indicates, Barlia was not only tasked with inviting guests to parties, but also carried out other ceremonious duties related to a wedding celebration. For instance, the exchange of the mandada between the bride and groom that Calvo mentions — a tray of gifts and sweets — was facilitated by Barlia.

He also had an important responsibility after the wedding ceremony. During a Jewish wedding, the groom provides his bride with a contract known as a ketuba outlining his responsibilities to her. The bride must keep the ketuba in a safe place — often in her mother’s home. Thus, after the wedding ceremony, Barlia also delivered the ketuba to the bride’s mother.2

The role of the kombidador also reflected the significance that Jewish families placed on wedding celebrations. The immense effort expended on hosting elaborate celebrations — full of carefully prepared foods, music, singing, and presenting gifts — are all components of alegrar a el novyo i la novya — making the bride and groom happy. Not only is it simply a kind gesture to celebrate the new couple, but doing so is akin to observing Shabbat and other holidays — it is a mitsva (commandment).

The Me-am Lo’ez, a famous Ladino commentary on the Hebrew bible and an encyclopedia of Sephardic laws and customs, records this commandment in a commentary on the Book of Genesis:

I es mitsva de alegrar a el novyo i la novya i kantar i baylar delantre de eyos. I dieron Hakhamim lesensia de demodar la avla diziendo ke es ermoza a un ke no es...

"And it is a mitsva [commandment] to make the bride and groom happy by singing and dancing in their presence. The hakhamim [sages] even gave us license to lie and praise the bride for her beauty — even when it does not exist..."

Wedding guests had religious obligations at the celebration

While this comment introduces an unusual moral compromise offered by the sages, it also provides a lens through which to view the importance of the kombidador, and by extension, the musafir, or “guest.” The two roles are inextricably tied together: The kombidador was not simply tasked with a responsibility to fill the room with wedding guests; rather, he created the opportunity for the musafir to fulfill the important mitsva of celebrating the bride and groom. Only through the kombidador’s invitation would guests know that they are invited to participate in this lofty celebration.

The distinctly Turkish origins of the word musafir position the two roles as complementary beyond the practical responsibilities they carry. Linguistically, the kombidador and the musafir represent a fusion of cultures planted within Ladino, but also extends to the character and quality of the wedding celebrations of which they are a part. Beyond the wedding celebration, the inextricable relationship between kombidador and musafir reminds us of the historic relationship between Sepharadim and their neighbors as expressed in the Ladino language and Sephardic culture.

The innovation of printed wedding invitations and its social effects

Barlia’s job began to be replaced by printed wedding invitations by the 1920s, both because of the increased access to printing technologies, and also because the Seattle Sephardic community began to disperse geographically. People moved beyond the Central District to other parts of the city or to other parts of the country and beyond.

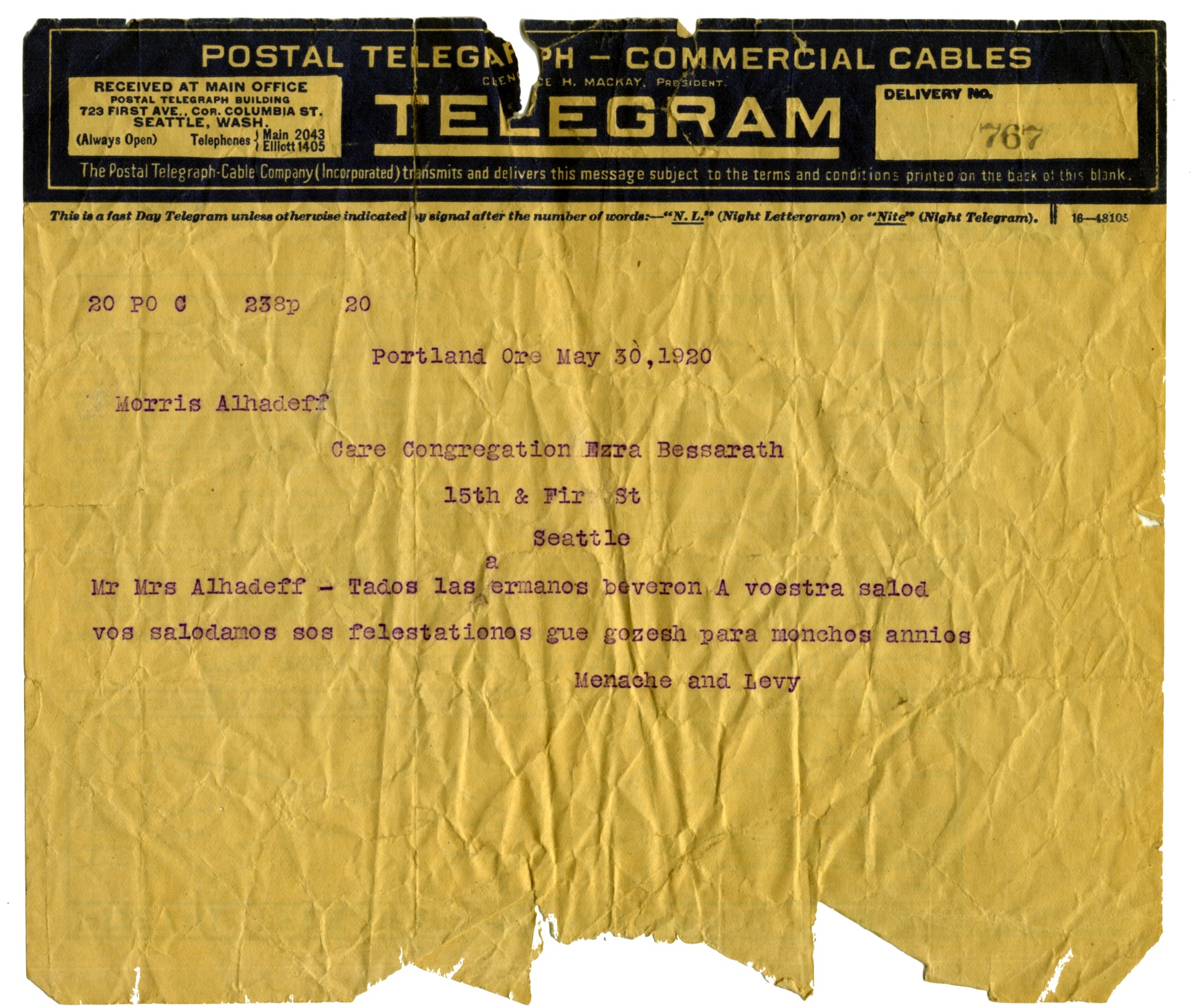

The first signs of geographic expansion can be seen in a series of telegrams sent to Seattle from across the United States congratulating Moshe and "Behora" Rebecca Alhadeff on their upcoming wedding. Not only did some of the telegrams come from West Coast cities such as Portland and Los Angeles, but they even came from as far as Atlanta and New York.

![Invitation to the wedding of Ester Sidi and Avner [George] Alhadeff Invitation to the wedding of Ester Sidi and Avner [George] Alhadeff](http://jewishstudies.washington.edu/omeka/files/fullsize/cbdf802ee6b9b4f98e020d93d8a07cba.jpg)

Multilingual invitation to the wedding of Esther Sidi and George Alhadeff in Seattle. The bottom Ladino text is written in rashi letters. Click to enlarge.

Wedding invitations in Ladino

One of the earliest preserved wedding invitations is for the marriage of Esther Sidi to George Alhadeff in 1923, printed in English and Ladino in rashi script. The inclusion of both languages represents the status of Seattle’s Sephardic Jews as still wed to their historic language, Ladino, while beginning to embrace the language of their new country of residence. It is also noteworthy that the invitations were printed across the country in New York by La Amerika, one of the most famous Ladino newspapers in the United States at the time -- a sign that despite vast distances, Sephardic families and institutions remained connected.

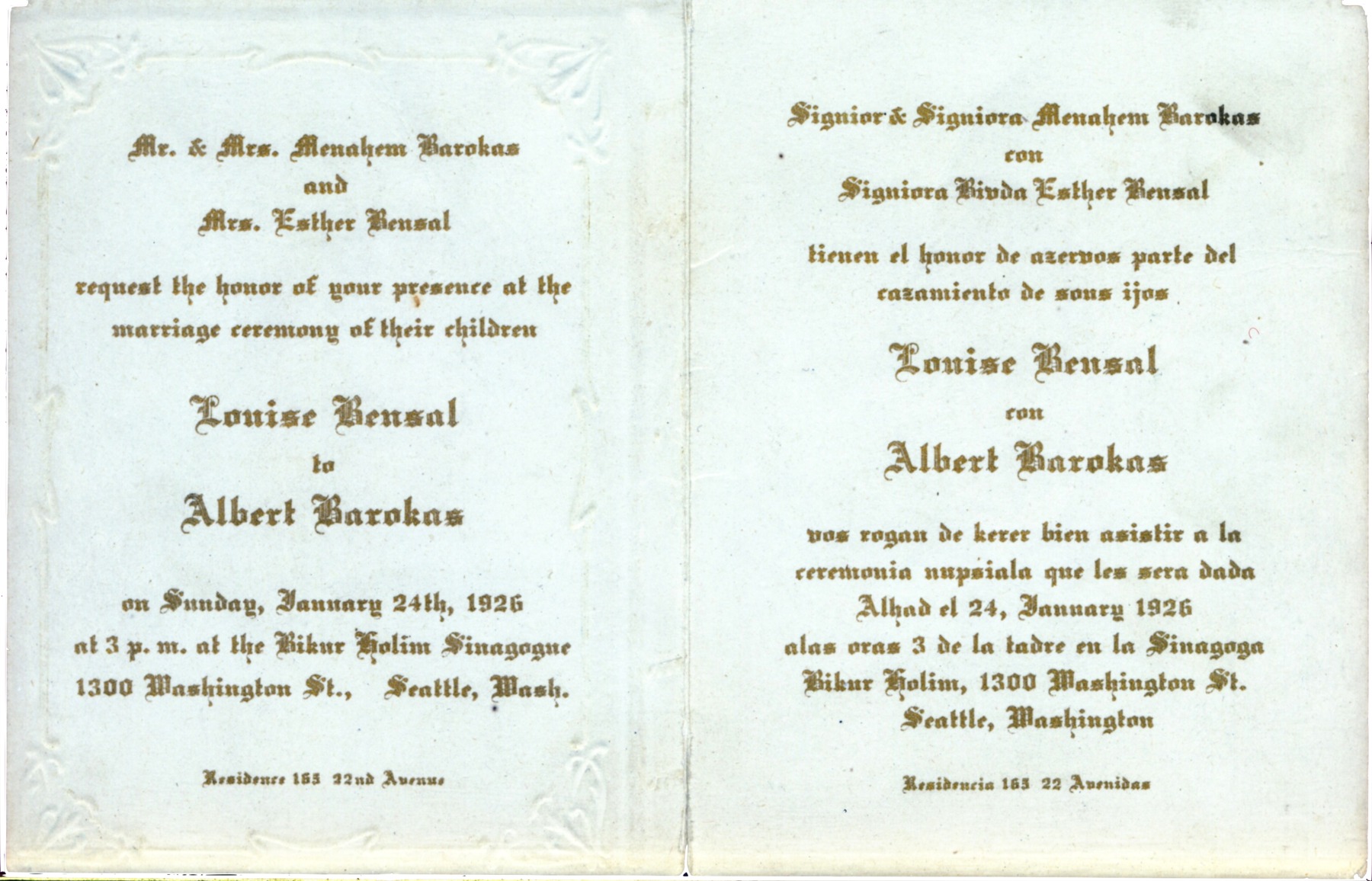

In 1926, the invitation for Louise Bensal and Albert Barokas’ wedding (lead image above) was delivered in the mail. While the cards still featured Ladino and English, the Ladino transitioned to Latin characters. Apparently, in just three short years, there was a precipitous decline in the community’s ability to read Ladino written in Hebrew characters in Seattle.

And finally, in English

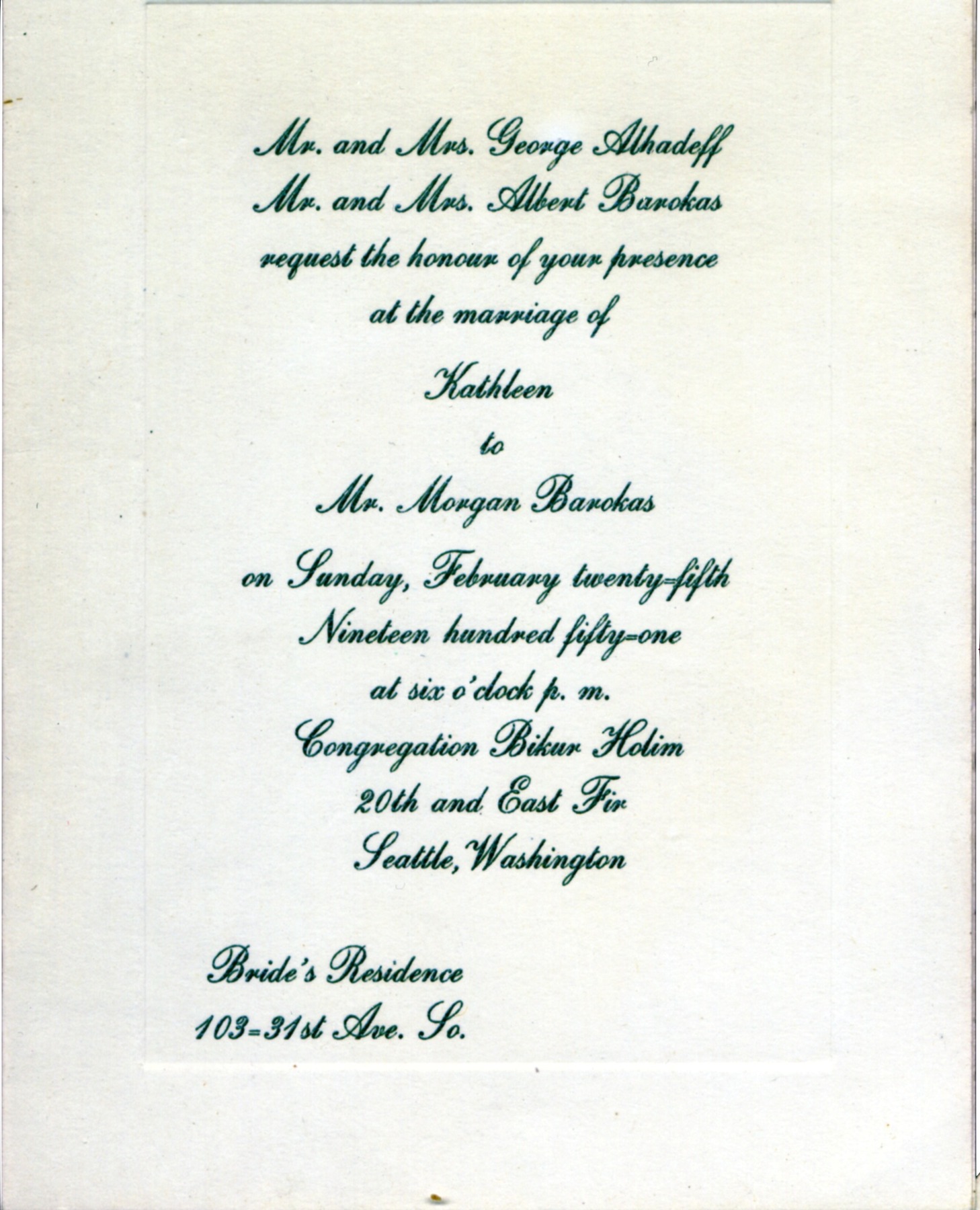

Almost thirty years after the respective Alhadeff and Barokas weddings, the two families would converge for the marriage of their own children: In 1951 Kathleen Alhadeff married Morgan Barokas. Not even a single Ladino word appeared on the English invitation.

From kombidador to printed invite: The price of change

A kombidador is only practical in small neighborhoods where friends and family live next door. The role became obsolete as social circles expanded over greater distance and new technologies like print and post emerged. While there was much to gain from the Seattle Sephardic community expanding beyond a few blocks in the Central District, it also came at a cost, in terms of social cohesion, the loss of the Ladino language, and the loss of many customs and social roles — the kombidador included.

References:

1. Transcription courtesy Jewish Archives Project of the Washington State Jewish Historical Society and the University Archives and Manuscripts Division, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

2. Maimon, Bension. Albert S. Maimon and Eugene Norman, eds. The Beauty of Sephardic Life: Scholarly, Humorous & Personal Reflections. Seattle: MaimonIdeas Publishing, 1993. pg. 171.