Kame'ot: Amulets for Newborn Babies

Summary:

- Sepharadim throughout the Ottoman world shared a belief in demons, known in Hebrew and Ladino as shedim and danyadores, respectively.

- People were particularly wary of demons during pregnancy.

- Sepharadim kept the demons at bay with a variety of folk practices, such as kame'ot, or amulets.

- Folk practices became far less common as more Sepharadim immigrated to the United States.

Throughout the Sephardic world, many of life's most imporant events were accompanied by numerous folk practices. All too often, scholars and Jewish community leaders denigrate folk practices in seeking to distance themselves from “superstition.” But with careful attention, these practices, which formed an integral part of the Sephardic world, provide insights into individual and collective concerns, and the various methods that Jews developed to address them and soothe their anxieties.

Why were folk practices prevalent during pregnancy?

While Sepharadim certainly celebrated new life, the prevalence of folk practices during pregnancy and birth suggests that they were still apprehensive about danyadores or shedim — evil spirits or demons. There was nothing unusual about belief in evil spirits: Jewish communities around the world, Ashkenazim and Sepharadim alike, and many other communities — Christians, Muslims, and others — embraced a vast and elaborate world of folk practices to ward off the “evil eye.”

Sepharadim warded off the evil eye in many ways

Different communities had their own ways of keeping the evil spirits at bay — both during pregnancy and once the child was born. Spitting on or near a baby, followed by a short expression such as “poo poo!” is perhaps the most universal across cultures. In Salonica, for example, expecting mothers often relied on older women who were adept at mixing potions and reciting incantations to keep them safe during their pregnancies.1 Similarly, in Gallipoli -- a city on Turkey's eastern peninusla -- a sprig of rue was placed next to a pregnant woman’s head to protect her from the evil eye.2

Kame'ot: Protective amulets

One of the most common techniques used to keep the demons at bay was the use of kame’ot, or amulets. If celebratory kantikas as an oral practice were the women’s domain, the kame’ot, part of written culture, were the man’s domain.

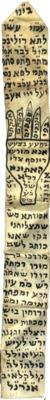

Throughout the Ottoman world, rabbis engaged in a variety of practices relating to kame’ot. In one tradition, scribes would write out shadayim — two paper kame’ot inscribed with the names of angels and that of the demon Lilith, who was believed to be notorious for harming newborns. The mother would pin one of the shadayim to herself and the other onto her baby to protect themselves from Lilith. Since Lilith purportedly had wings, many times the kame’ot would be fashioned with wing shapes, as well.3

Kame'ot in the Old World

In Salonica and other towns throughout the Ottoman Empire, scribes often composed kame’ot with elaborate mystical formulas that invoked the names of angels, called upon to protect the newborn. Written on long, rectangular pieces of parchment or fabric, and then folded up into a small triangle package resembling a savory Sephardic pastry known as a fila, the kame’a would accompany the newborn wherever he or she went, including into adulthood. The kame’a would sometimes be sewn shut, attached to a string, and worn around the neck, or slipped into a wallet.

In his engaging memoir, one of the great Ladino journalists and novelists of the twentieth century, Elia Carmona, from Istanbul, attributed his professional success and fame to the kame’a he carried with him since birth. He believed the amulet enabled him to overcome all the obstacles life threw at him.

Kame'ot in the New World

Many of the kame'ot from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection were preserved by Avraham Maimon, who came from Tekirdag (a town near Istanbul) to Seattle in 1924 to serve as a rabbi. He preserved several kame’ot in various scripts, but it remains unclear whether he himself composed them.

If Rabbi Maimon did compose these amulets, it seems that he eventually disregarded the harmful spirits of the old world when he immigrated to the United States: His son Bension recalls Rabbi Maimon saying, “As far as Seattle is concerned, we shouldn’t worry, because these [demons] didn’t cross the Atlantic Ocean.”4

Other Sepharadim who immigrated to the United States did not readily dismiss the possibility that the demons followed them to their new homes. Professor Devin Naar’s great-grandfather, Rabbi Benjamin Naar, a practitioner of kabbalah, composed kame’ot in the Salonican fashion described above both in his native city, and even after he immigrated to the United States with his family in 1924.

Unlike for Rabbi Maimon and the Seattle community, for Rabbi Naar and his communities in New York and New Jersey, the practice of composing kame’ot continued for another generation — even into the immediate post-World War II years. Some of Rabbi Naar's descendants and other community members still possess their kame’ot today.

From this perspective, it would seem that demons may have indeed crossed the Atlantic Ocean — but perhaps they did not succeed in making the train ride all the way to the Pacific Northwest.

Why should we study folk practices?

Even today, certain customs and traditions that were once deemed “superstitious” remain delegitimized and underexplored areas of study, both among academics and even within Jewish communities. While classical text-based sources in Judaism, such as the Bible, Talmud, rabbinic rulings, and even kabbalah have been granted rigorous academic attention and are comfortably discussed in Jewish circles, these are not the only sources for the multitude of customs practiced by Sepharadim. Folk practices that are sometimes at odds with classical rabbinic thought, having drawn influence from Christian Spain and the Muslim Ottoman Empire — whether political, artistic, or phsycological — all figure in to the tapestry of Sephardic customs. And many times, these folk practices offer valuable sociological insights into the communities in which they were practiced, and must be studied and discussed as openly as customs originating from more “typical” text-based sources.

Folk practices shed light on a Sephardic worldview

Especially in the absence of modern medicine, pregnancy was dangerous and often much more debilitating than it is today. Even into the early twentieth century, some cities with sizeable populations in the Ottoman Empire did not have electricity. Perhaps against this backdrop the danyadores can be seen as a manifestation of the fears that accompanied daily life in a world without the modern technologies we enjoy today—especially during pregnancy, when illness and disease could have disastrous consequences. That communities chose to acknowledge the tenuous nature of this life cycle event with carefully written, wearable kame’ot may illustrate a certain value placed on new life and the wish to protect it at all costs.

References:

1. Molho, Michael. Alfred A. Zara, trans., Robert Bedford, ed. Traditions and Customs of the Sephardic Jews of Salonica. New York: Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, 1994. pg. 47.

2. Levy, Isaac Jack, Rosemary Zumwalt. Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits, Healing the Sick. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001. pg. 97.

3. Gaguine, Shem Tov. Keter Shem Tov. Ramsgate, England, 1934. Reprint, Jerusalem: Israel, 1998. Section 34:766.

4. Maimon, Bension. Albert S. Maimon and Eugene Norman, eds. The Beauty of Sephardic Life: Scholarly, Humorous & Personal Reflections. Seattle: MaimonIdeas Publishing, 1993. pg. 188.