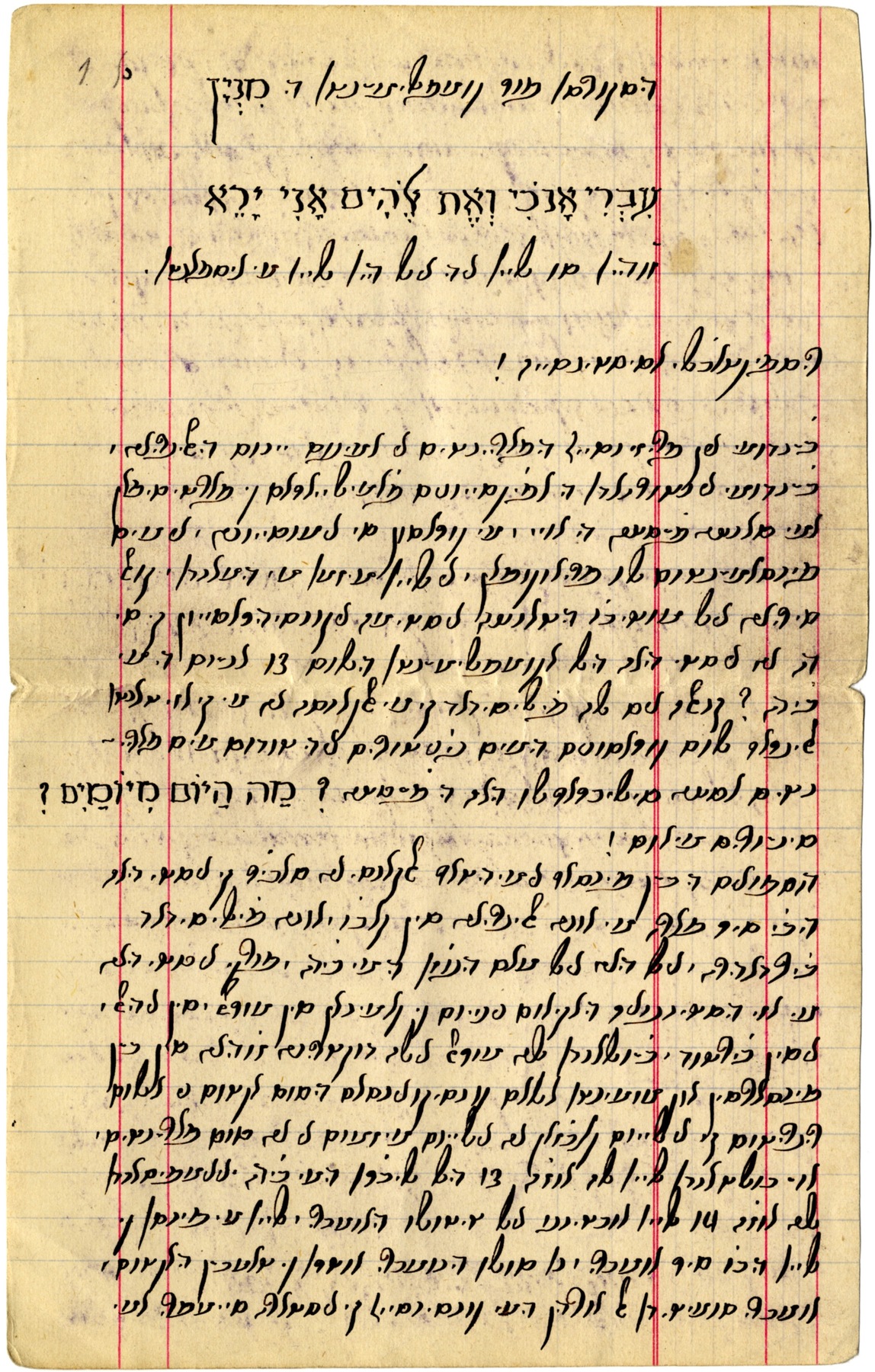

Set of tefilin first donned on the day of a boy’s bar mitsva. These tefilin are from the Island of Rhodes, once home to a large Sephardic community before the Holocaust. Courtesy of Al Shemarya.

Summary:

- The bar mitsva as we know it today is a recent innovation for both Sepharadim and Ashkenazim.

- Technically, a bar mitsva only serves to mark the day a boy turns thirteen and can particpate fully in Jewish commandments.

- Ashkenazi Jews were the first to incorporate a ceremony in the synagogue and more elaborate celebrations to mark the bar mitsva.

- Sepharadim in throughout the Mediterranean and the United States soon followed suit.

The pinnacle moment of most bar and bat mitsva celebrations today is a speech given by the young boy or girl. This practice has become such a fixture of the Jewish coming-of-age celebration that its cadence is almost formulaic: the child, now turned Jewish adult, thanks family, teachers, and friends — especially those who have come from near and far to celebrate this special day — and shares a kernel of Jewish wisdom with the audience.

Yet until relatively recently, the bar mitsva was hardly the formal and often elaborate ceremony it is today. This is particularly true among Sephardic Jews. How, when, and why did Jews from the Ottoman Empire and the communities they established in the United States develop the practice of the bar mitsva speech?

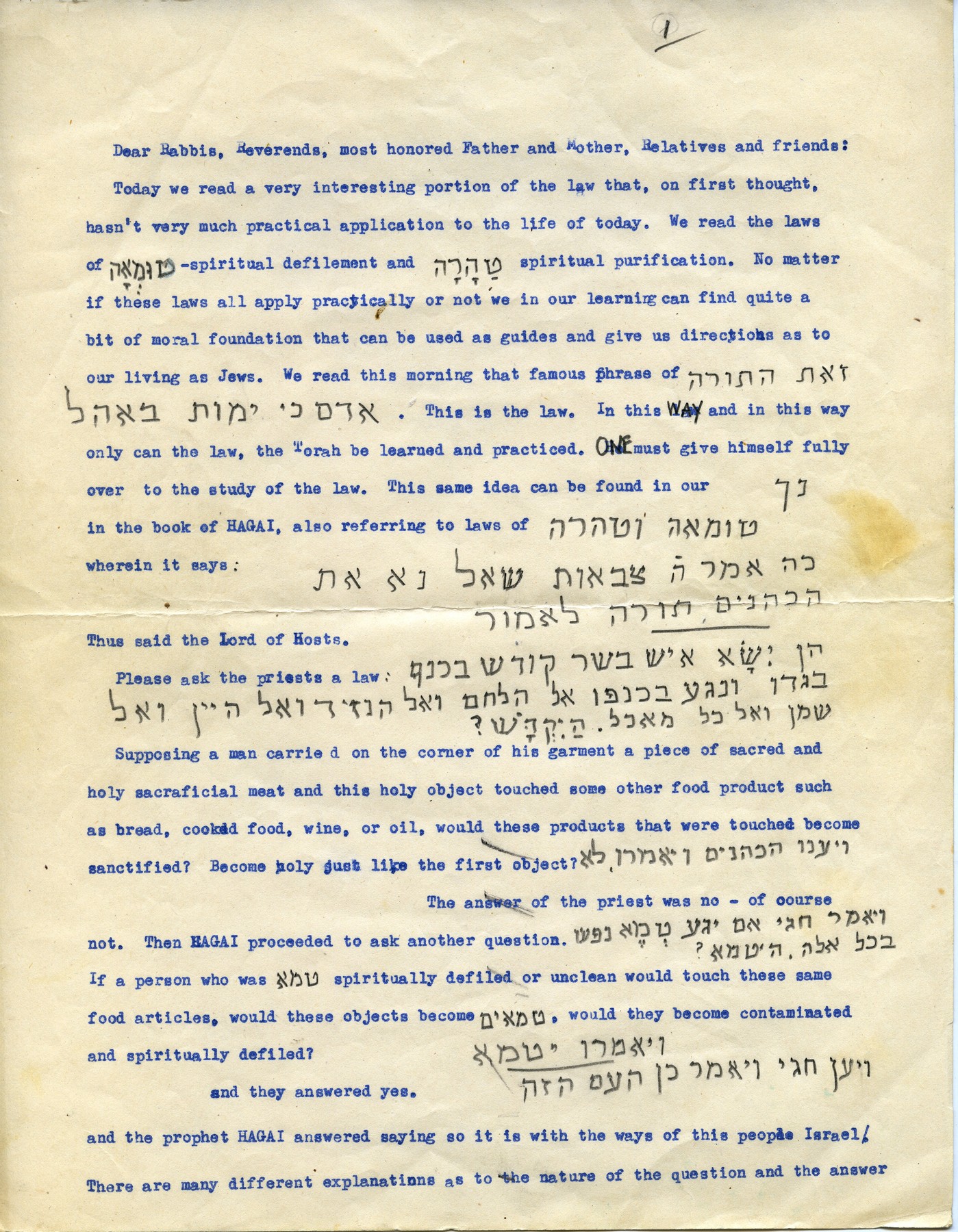

Rabbi Isidore Kahan (second from left) with bar mitsva boys at Seattle’s Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, 1939. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

The traditional bar mitsva

Fundamentally, the bar or bat mitsva marks the day a boy turns thirteen, or a girl turns twelve, and enters Jewish adulthood. Subsequently they can participate more fully in Jewish life and its obligations. In Ladino the occasion is known as kumplir minyan, “to complete the minyan,” which refers to a new obligation young boys can now fulfil as Jewish adults: Some prayers require a quorum of ten adult Jewish men, known as a minyan, in order to be said; thus the phrase kumplir minyan refers to a young boy being counted within that quorum.

In 1950s Istanbul, an enhanced bar mitsva becomes the new standard

In Nisim Behar’s El gid para el pratikante (Istanbul, 1957), his guide to Jewish law and Sephardic customs, we can see the bar mitsva emerging as the modern ceremony that we know today. Behar mentions that a bar mitsva boy will not only mark the day by donning tefilin, or phylacteries, for the first time (only Jewish adults can wear tefilin during prayer) — a moment that could easily pass by unceremoniously — but that the young boy will also read the coinciding weekly portion from a Torah scroll, deliver a speech, and enjoy a party with family and friends:

El Dia de Bar-Mitsva se veste Tefilin, i si es lunes o cueves suve al Sefer-Torah…Si el ijiko aze Derasa (deskorso), la Seuda se konta komo Tseudat-Mitsva, mezmo ke akel dia no es el dia de Bar-Mitsva.

“On the day of the Bar Mitsva the boy wears tefilin [phylacteries], and if it is Monday or Thursday, he will go up [receive an aliya] to the Torah [which is only read Monday, Thursday, and Shabbat]…The son gives a derasha [speech], the seuda [meal] is counted as seudat mitsva [festive meal], even if that day is not his actual bar mitsva.”

Ottoman Sepharadim were inspired by Ashkenazim decades earlier

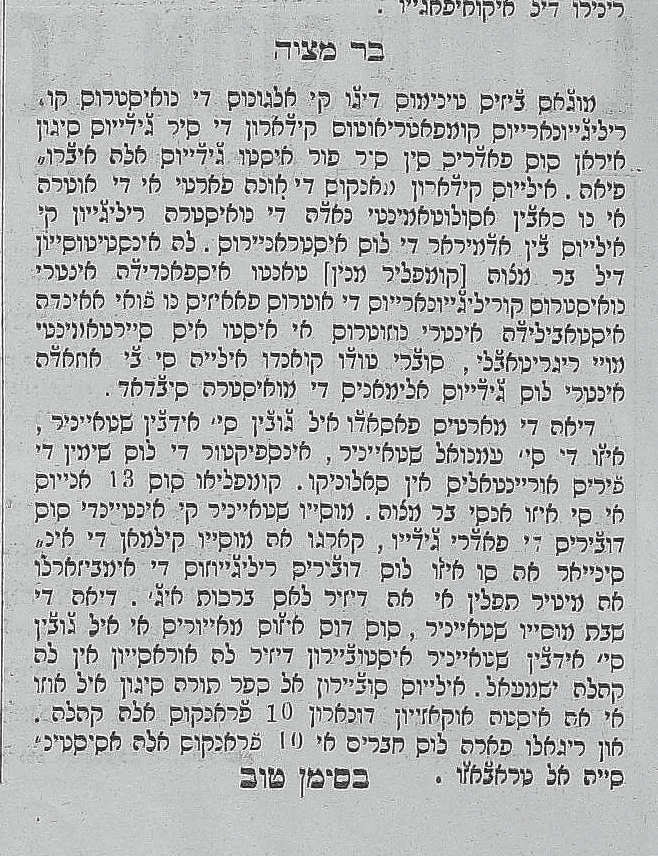

Article from the Salonican Ladino newspaper El avenir (1900) advocating for an enhanced bar mitsva that emulated those of a local Ashkenazi congregation

If we go back in time several decades, however, we discover not only that the bar mitsva lacked much of the ceremonial aspects that it would later acquire, but that for Sephardic communities, there was little celebration at all — and certainly no speech.

In Salonica, for instance, the Ladino newspaper El avenir reported in 1900 that beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire, Jewish communities celebrated the bar mitsva, but that the custom was totally unknown to local Sepharadim (hence why the newspaper had to explain what the term bar mitsva meant: kumplir minyan). The article continues to report that a German Jewish family arranged for his son to have a bar mitsva at one of the local synagogues (the father was stationed in Salonica as an official with the local railway company). The newspaper saw this innovative ceremony as useful for instilling a sense of Jewish identity and responsibility for Jews coming of age and advocated for Sepharadim to follow suit.

By the 1930s, not only was the bar mitsva ceremony a common practice in Salonica and other Sephardic communities, but so, too, was the bar mitsva speech. Bar mitsva speeches of communal notables even began to be published in newspapers.

In an interview conducted in Ladino by Seattle scholar Albert Adatto, Solomon Shaki, a Holocaust survivor who served as caretaker of the Jewish cemetery, recalls the day of his bar mitsva in Salonica just before World War II:

ALBERT ADATTO: Komplites minyan?

SOLOMON SHAKI: Si. La perasha mia ke kompli minyan era va-yikkhu li teruma. La aftara era va-Adonai natan hokhma li-Shelomo.”Yo me yamo Salomo, i la aftara es ke da Dio hokhma a Shelomo.

ADATTO: Dates un deskurso en Ladino?

SHAKI : Si, es deskurso era komposado, alav a-shalom, a la hakham i profesor Barukh ben Yaakov, grande profesor de Salonik de lingua Ebrea i de Tora.

ADATTO: Bueno, mil grasias.

Translation:

ADATTO: Did you have a bar mitsva?

SHAKI: Yes. My Torah portion that I read was that of va-yikkhu li teruma (“Take for me an offering”).1 My haftara portion [from the Prophets] was that of va-Adonai natan hokhma li-Shelomo (“And God gave Solomon wisdom”).2 My name is Solomon, and my haftara was about God giving King Solomon wisdom.

ADATTO: Did you give a speech in Ladino?

SHAKI: Yes, my speech was written by Barukh ben Yaakov, may he rest in peace, who was an eminent professor of Hebrew and Torah studies in Salonica.3

ADATTO: Excellent, thank you very much.

Even today, parents and teachers help their children with their bar and bat mitsva speeches. But prior to World War II, as Shaki’s testimony suggests, the custom was for teachers to ghost write their pupils’ speech en toto.

The transformation of the bar mitsva speech in Seattle

In Seattle, the added practice of bar mitsva boys delivering sermons evolved in its own way. In 1909, when Charles Alhadeff turned 13, he recalls that his bar mitsva at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth at 15th and Fir Street passed without much fanfare:

HOWARD DROKER: Did you go to Sephardic Talmud Torah [religious school]?

CHARLES ALHADEFF: Yes, as a youngster and we called it heder. I went after school until I was possibly 13 — until my bar mitsva, which was a very simple ceremony. I was 13, I went one Sunday morning — I remember my father didn’t even come — to the synagogue at 15th and Fir and said a few prayers, and my mother had a little repast there, and that was it. No speeches and no long orations. I held the Torah and read a few lines as I recall, so that I learned to read Hebrew, and although they tried to teach us Hebrew at the time, we weren’t much interested in learning anything, and to this day I can follow, I can read it, but I have very little conception of what it says.4

Alhadeff’s unceremonious bar mitsva was standard for families who came from the Island of Rhodes, where Alhadeff’s family had roots: Jews on Rhodes did not incorporate speeches into their bar mitsvas prior to World War II.5

An inside look at a bar mitsva speech from Congregation Ezra Bessaroth

By 1935, expectations at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth had changed: Menache Israel, a first cousin of Charlie Alhadeff, turned thirteen that year and spoke in Ladino at his bar mitsva. His speech is preserved in two formats: one copy is written in soletreo, the Hebrew cursive script used by Sepharadim to write in Ladino, and the other is typed in Latin script. Since Israel could not read soletreo himself, it is likely that he read from the typed version at his bar mitsva.6

Israel identifies the fundamental transformation that the bar mitsva confers upon young boys. Ayer fue ona kreatura y oy so un ombre entre los ombres. Un membro cerinsioso del pueblo Israel (“Yesterday I was a child, and today I am a man among men. A serious member of the people of Israel”). As Menache celebrates his new status as an adult within the community of Israel, he also creatively references his family name, which is also Israel. Y tambien un vero ezo de la famia Israel, un adopta de la nasion eskushida (“And I am also a part of the family of Israel, a member of the chosen nation”). Perhaps this is also a manifestation of the notion of alkunyas — Sephardic surnames that families carry with pride.

One wonders if perhaps the situation recorded in Salonica’s El avenir repeated itself in Seattle: Did members of Ezra Bessaroth look toward the Ashkenazim at the neighboring Bikur Cholim synagogue and decide to emulate their bar mitsvas, just as the Salonican Sephardim did with the local German Jewish family?

A bar mitsva speech from Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation

Similarly, when Albert Maimon celebrated his bar mitsva at Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation in 1954, he also delivered a speech — but this time, in English. The language used for any sermon in a synagogue historically reflects the local vernacular of that community; therefore, Israel and Maimon’s speeches offer a way to trace the shifting use of languages among Sephardic Jews in Seattle throughout the twentieth century from Ladino to English.

A noteworthy feature of Maimon’s speech that is particularly relevant to the day of his bar mitsva is an analysis of the Jewish law specifying that the tefilin should always be worn on a person’s non-dominant hand. While Maimon was left-handed, his father encouraged him to learn to write with his right hand, leaving Maimon ambidextrous. Which hand, then, was considered Maimon’s dominant hand, and around which arm was he to wrap his tefilin?

In his speech, Maimon presents the rationale using the ruling of the Shulhan Arukh, the primary guiding legal text for Sepharadim by Rabbi Yosef Caro, first compiled in the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the expulsion from Spain. Maimon’s use of the Shulhan Arukh in his bar mitsva speech indicates a distinctly Sephardic approach to his quandary regarding the tefilin.

The Sephardic bar mitsva today

By the time Nisim Behar was writing El gid in 1957, the bar mitsva ceremony, enhanced by the speech, had become so commonplace that Behar codified it: Although not purporting that delivering a speech was Jewish law, the fact that Behar included it in his guidebook indicates that he viewed the practice as integral to celebrating a boy’s entrance into Jewish adulthood.

Today bar mitsvas are formal affairs in most Sepharadi and Ashkenazi synagogues across denominations, and the speech is an expectation and educational milestone for young boys and girls. But for all Jews, this element of the celebration is a modern innovation intended to imbue the occasion with greater significance and promote Jewish education.

For Sepharadim especially, adding the speech to the bar mitsva initially suggests an emerging self-consciousness in dialogue with neighboring Ashkenazim and a desire to emulate their restyling of a centuries-old tradition. Yet the content of the speeches profiled here also carried distinctly Sephardic themes: For Israel, it was the pride in his family name; for Maimon, it was the foundational texts he cited. Although inspired by an Ashkenazi enterprise, Sepharadim infused bar mitsva speeches with messages that would resonate with young men growing up in a Sephardic community.

References:

1. Exodus 25:1 – 27:19.

2. 1 Kings 5:26 – 6:13.

3. For more information on Barukh ben Yaakov, see: Naar, Devin. Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece (2016), pp. 202-206.

See also: Naar, Devin. “Fashioning the “Mother of Israel”: The Ottoman Jewish Historical Narrative and the Image of Jewish Salonica.” Jewish History 28, no. 3/4 (2014): 337-72.

4. All transcriptions courtesy the Jewish Archives Project of the Washington State Jewish Historical Society and the University Archives and Manuscripts Division, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. All audio courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

5. Benveniste, Dr. Irvine interview on May 14, 1972, #2, 2:50-3:10. Rhodes Jewish Museum.

6. Mezistrano, Makena. “‘Hidden manuscripts, come out!’: Seattle Sephardic Legacies highlights Ladino literature.” Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, 2019.