Attendees brought family artifacts to the June 2nd, 2019 Seattle Sephardic Legacies event, such as this scroll of the Book of Esther (megila).

By Makena Mezistrano

“There are ever so many manuscripts, books and documents, lying hidden among people’s possessions, or buried in the communities’ archives…Let them call to the hidden manuscripts: come out! And to our ancient Ottoman histories: reveal yourselves!” Abraham Danon, 1888.

In his bi-monthly Ottoman Jewish journal El Progresso/Yosef Da’at (Edirne, 1888), Abraham Danon called on his readers to unearth their scattered caches of archival texts. As a rabbi and educator, Danon advocated that his community gain access to their history as told through their manuscripts. From his desk in 19th century Edirne, Danon could not have foreseen that more than a century later, his summons would be answered in Seattle.

On June 2nd, 2019, the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies’ Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington hosted a public program entitled, “Seattle Sephardic Legacies.” Sponsored by a National Endowment for the Humanities Common Heritage Grant, the event featured a multimedia lecture by Sephardic Studies Program Chair Devin Naar that highlighted the results of the past five years building the world’s largest repository of digitized Ladino texts; an open-house scanning opportunity for people to share and digitize family artifacts; an exhibition featuring the artifacts and stories of a dozen Seattle Sephardic families; and a kosher reception of Sephardic cuisine. The event brought to fruition a 21st century digital manifestation of Danon’s call more 130 years ago for those hidden Sephardic manuscripts to finally see the light of day.

Welcoming the nearly 250 attendees–students and faculty from many departments, members of the Seattle Sephardic community, and the general public–to the HUB Lyceum on UW’s Seattle campus, Reşat Kasaba, Director of the Jackson School of International Studies, highlighted the centrality of the Sephardic Studies Program and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies to the work of the Jackson School. He also reflected on his personal interest in the work of the Sephardic Studies program given his own roots in Turkey and his scholarship on the Ottoman Empire.

Naar’s multimedia lecture then traced the past and future plans of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection (SSDC), a cornerstone of the Sephardic Studies Program that has transformed the University of Washington into a world leader in the field. Naar explained that the seeds for the SSDC were planted at the initiative of members of Seattle’s Sephardic community. Back in 2011, during one of his first visits to the Capeluto family’s Seattle Curtain Manufacturing Company in the Central District to attend a meeting of the Ladineros—a Ladino conversation group that now meets at a local retirement home—Naar was approached by one of the participants, Menache Israel, with a mysterious document and a request to decipher it.

A long time secretary of Seattle’s Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, Israel understood Ladino fluently but could not read soletreo, the now defunct Sephardic Hebrew cursive script in which the document was written. As Naar had mastered soletreo to decipher his own family documents and for his dissertation research, he identified the document as an ethical will written in Ladino by Israel’s own grandfather, Nissim Israel. Naar began to read the text for Israel who became emotional upon hearing the words of his grandfather transmitted to him seventy years later.

The exchange prompted Naar to inquire with the city’s Sephardic institutions about what other kinds of documents—printed or handwritten—were waiting to be discovered. Soon Albert Maimon and Lilly DeJaen, members of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, led Naar to what became known as “the Safeway archives,” a collection of rare books stored in Safeway shopping bags in the synagogue storage room. Among the items were the notebooks of the well-known journalist and teacher Albert Levy as well as one of the oldest texts yet to be uncovered: Sefer Shevet Musar, a book of Jewish ethics in Ladino (Istanbul, 1741). Naar soon connected with Richard Adatto, son of Albert Adatto, a pioneer in the field of Sephardic Studies, who shared his father’s meticulously preserved collection of hundreds of Ladino books with accompanying notes penned by Albert Adatto himself.

These private collections, plus many smaller collections or single items from other individuals shared by over eighty community members, formed the basis for the first 800 items in the collection. Since then, thanks to support from the Sephardic Studies Founders Circle, and under the supervision of Sephardic Studies Research Coordinator Ty Alhadeff, the program has cataloged nearly 2,050 items and has digitized over 400 printed Ladino titles that now comprise the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection (SSDC). Thanks to the collaboration of the University of Washington Libraries, a subset of these texts are now available via the UW Libraries Digital Collections portal.

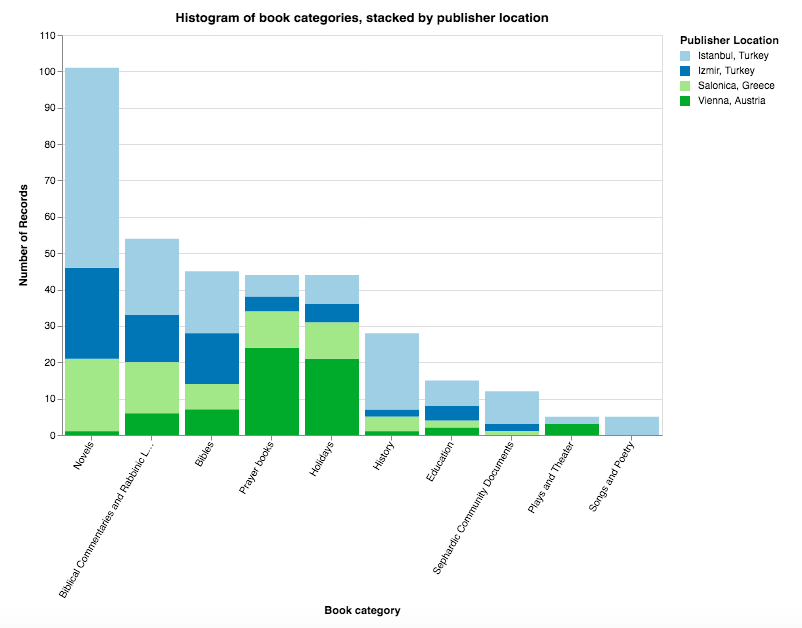

Using data visualizations created by Benjamin Lee, a PhD candidate in computer science and engineering at the UW, Naar presented a statistical overview of the digitized texts in the SSDC. He pointed out some perhaps unsuspecting features of the collection: For one, most of the digitized texts—which include prayer books, bibles, and novels, among other categories—were published in the historic centers of Sephardic culture like Izmir, Istanbul, and Salonica. Yet surprisingly, Vienna produced the next highest volume of published Ladino books collected in Seattle despite the city being known as a center of Ashkenazi Jews and never having been part of the Ottoman Empire.

Histogram of Ladino published book categories overlaid with publisher location by Benjamin Lee.

Naar’s presentation also showed how items in the SSDC challenge long-standing assumptions and prejudices about Ladino literature. Naar pointed to Heinrich Graetz, one of the most famous Jewish historians of the 19th century, who claimed that Jews who settled in the Ottoman Empire after the expulsion from Spain “did not produce a single great genius who originated ideas to stimulate future ages, nor mark out a new thought for men of average intelligence.” Similarly dismissive assertions have continued into the 21st century; can anyone today name a famous Ladino novelist?

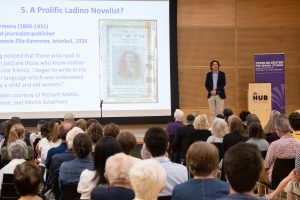

Naar’s slide of Elia Karmona, one of the most prolific Ladino novelists of the 20th century.

Naar argued that Sephardic Jews did indeed produce a wide range of literature in Ladino over the past centuries. The problem is not that it does not exist; rather, the problem is that no one ever tried to look for it and study it systematically. In order for such studies to be possible and for perceptions of Ladino culture to change, Ladino literature has to be made accessible—which is precisely the goal of the SSDC.

As an example, Naar highlighted the writings of Elia Karmona, one of the most prolific Ladino novelists of the 20th century with more than 40 novels to his credit. That the SSDC houses more than a dozen of Karmona’s works is a testament to the fact that the books were apparently so treasured and enjoyed by Karmona’s readers that they brought them all the way to Seattle!

“Instead of burying the Ladino culture…Sephardic Jews [spurred by Naar’s call] dug through their belongings for something bigger than them, something that will outlive all of them and hopefully inform future generations that hopefully will not be lost,” said Nazreth Abraham, one of Naar’s undergraduate students who attended the event.

The program has completed a series of successful digitization projects, and Naar indicated that next steps will include deeper research and translation of Ladino materials as well as greater dissemination of the findings, all toward the goal of making Ladino texts and their translations more accessible to scholars, students, and the general public.

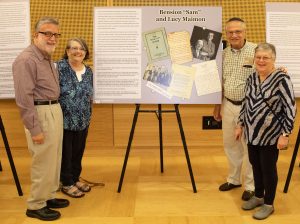

Attendees at the Seattle Sephardic Legacies event got an initial taste of SSDC’s contents and the stories these artifacts tell about Ladino language, culture, and community. Using scans of photos, books, stamps, passports, and other documents contributed to the collection, Ty Alhadeff and I prepared thirteen exhibition panels profiling Seattle Sephardic families and their artifacts. Each panels highlighted a noteworthy family with roots in the Ottoman Empire who came to Seattle in the early- to mid-twentieth century. Those profiled included: Albert Adatto and Emma Adatto Schlesinger; David and Kaden Alhadeff; Leo and Liza Azose; Jack and Louise Azose; Reverend David J. Behar; Reverend Samuel and Aliza Benaroya; Henry and Samhoula Benezra; Joseph and Rachel Benoliel; Bension “Sam” and Lucy Maimon; Rabbi Solomon Maimon; Professor David Romey; Reverend Morris and Esther Scharhon; and Rachel Shemarya.

Eugene and Esther Normand (left) with Al and Jeanne Maimon (right) pose next to their parent’s panel. Al and Esther are the children of Sam and Lucy Maimon.

Many attendees were direct descendants of those highlighted on the panels. As guests moved through the exhibition, they stopped to take photos next to their family posters. Many were related to multiple families profiled. Some were quite close generationally, like Al Maimon and his sister Esther Normand who are children of Sam and Lucy Maimon. Others were great-grandchildren, like Miri Azose Tilson, who came with her grandfather Mo Azose and posed next to the panel of Mo’s parents, Leo and Liza. Tilson is also related to Reverend Morris and Esther Scharhon, also profiled in the exhibition, who were her paternal grandmother’s parents.

Miri (Azose) Tilson with her grandfather, Mo Azose, next to the panel dedicated to Mo’s parents.

“I was blessed to attend this special event with my Papu [grandfather], and watch him turn into a gleeful young boy looking lovingly and proudly at the boards of his and my Nona’s [grandmother’s] families, while parading me around and introducing me as his granddaughter,” Tilson said. “There is a primitive sense of pride that one feels when referencing past generations, and the Seattle Sephardic Legacies event compounded those feelings and sentiments.”

A unique feature of this particular event was the onsite digitization opportunity facilitated by Perfect Image, a scanning and data conversion company that has been digitizing books, photographs, letters, and audio for the Sephardic Studies Program since 2014. Two museum-quality scanners were set up outside the event space in order to digitize items that guests were invited to bring. Single items that could be laid flat, such as photographs or passports, were scanned on a flatbed scanner. But for books with multiple pages, an Atiz scanner was used: As the book was carefully cradled, the scanner was able to capture images of each individual page at up to 600 pages an hour; when pages must be turned manually, that number is decreased by half.

Perfect Image staff used an Atiz scanner to digitize over 300 pages at the event.

“Digitalization has not only made archiving documents easier, but has also made preserving these documents more permanent,” reflected Adam Erie, another one of Naar’s undergraduate students who attended the event. “A digital copy of a document can’t erode and deteriorate over time like a hard copy can. [They] can also be replicated and shared in real time across the globe.”

Part of my role at the event was to manage the cataloging and intake of artifacts brought by attendees, which included photographing materials that might not fit in the scanners, such as jewelry or textiles. They also shared their stories. One of the most poignant stories accompanied a small scroll of the Book of Esther, or megila. The megila was from Italy, belonged to the Emenente family, and was shared with us by Susan Schauffer, who is related to the family through marriage. Schauffer related to me that during World War II the Emenentes fled to Switzerland, but before departing they buried some of their possessions near Lake Como, including this megila, and a talet, or prayer shawl, which I also photographed. After the war, the family managed to return to Lake Como and recovered the hidden items.

“The [Seattle] Sephardic Legacies event was a revelation for me,” said Betsy Wilson, Vice Provost for Digital Initiatives and Dean of University Libraries. “I saw first-hand the power that came from the university and the community coming together to create the transformative Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. This digital treasure trove not only provides worldwide, open access to rare and unique materials, but will also enable new digital scholarship and preserve the voices and artifacts of a significant community.”

As the “hidden manuscripts” that Abraham Danon wished to expose emerge now more than a century after his original call in 1888, many stories have begun to be told. Through the lecture and accompanying exhibition, the Seattle Sephardic Legacies event showed that the Sephardic experience in the Ottoman Empire and Seattle includes not only a rich history and literature, but, with greater digital access, will continue to stimulate future generations of scholars, students, and community members in Seattle and across the world.

This event was funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Common Heritage Grant.

Special thanks to Perfect Image for collaborating with us on this event and all of our past digitization projects. Thank you also to the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and the Jackson School of International Studies for supporting the Sephardic Studies Program.

All photos courtesy Meryl Schenker Photography.

Leave A Comment