Introduction

There are four main themes that run through this exhibition. We invite you to consider these themes as you examine the artifacts.

In the New World, the Old World transforms

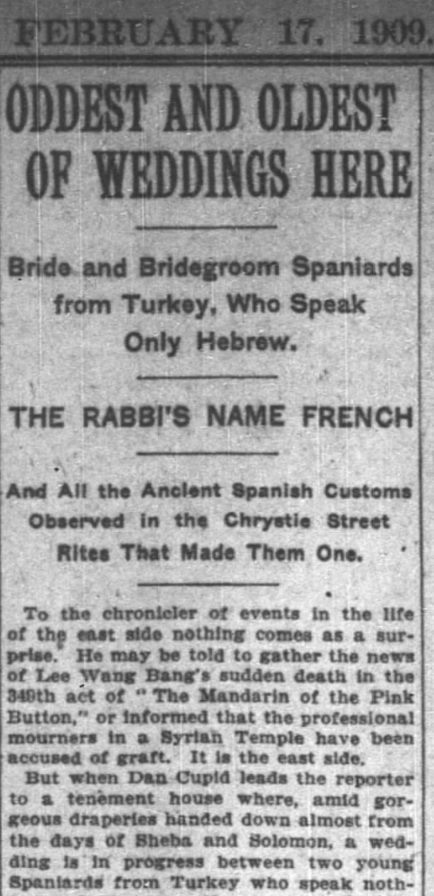

An article from The New York Times reveals the American perception held about Sephardic Jewish immigrants. Click to enlarge.

Many customs associated with Sephardic life cycles were not only transformed, but also lost, when Sepharadim moved from the Ottoman Empire to the United States. Other customs have remained largely unchanged. In some cases, the desire to hold on to these traditions represents an attachment to the “Old World” from which the Sepharadim originated. In some ways, the perpetuation or adaptation of long-held practices and beliefs enabled Sephardic Jews to either bridge or defy the dichotomy between the “Old World” and the “New.”

Deeply embedded within Muslim society in the Ottoman Empire, Sephardic Jews adopted and adapted certain perspectives and practices from their environment in the same way that Jews elsewhere, like all communities, are in dialogue with their neighbors and with dominant cultures.

But the United States in the early twentieth century proved detrimental and motivated some Sepharadim to shed certain distinguishing practices and beliefs in order to quietly integrate into the “New World.” In the eyes of many white Christian Americans, and to a certain extent, European Ashkenazi Jews, Sepharadim were Ottomans or Turks or “Orientals” first, Jews second. In some instances, Sephardic Jews and their customs were perceived as irredeemably “foreign” or “strange.” The prejudice that hounded new immigrants from Muslim-majority regions who settled in the New World, as well as the impact of antisemitism across the country, posed social roadblocks to many Sephardic Jews. Their culture sometimes suffered because of the obstacles, or had to be abandoned altogether. Such was the very high price of the “American Dream.”

Home is a sacred space

When we spoke about building an exhibit of Sephardic life cycle customs there was a clear consensus among our local community interlocutors and advisors who were first-generation Americans: we had to talk about the importance of home. This generation of Seattle Sepharadim emphasized that the home was integral to Sephardic life. In their parents’ country of origin, the home was a space for gathering, for prayer, for celebration, and for mourning. Home and synagogue were both sacred spaces. In the United States, home was a haven: a protected, private place to practice traditions in an unfettered manner, to speak Ladino, to be among los muestros — other Sepharadim. In short, we cannot address Sephardic customs without discussing the home. That is where tradition and custom lived.

Sephardic Jews, like Ashkenazi Jews, also adopted the American understanding of religion as associated with a place of worship. Whereas in the Ottoman Empire, all sites public and private could be embedded with sanctity, in the United States, the all encompassing Jewishness that pervaded every aspect of one's life became circumscribed. Synagogues were primary holy spaces, and the home was slowly relegated to the mundane. And as the space in which celebrations were held shifted, the customs associated with those spaces also changed.

When we address the home in our exhibit, although it is mostly from the perspective of Seattle Sepharadim, we are touching on the experience of expansion and Americanization felt by Sepharadim across the United States.

Oral traditions and written records are equally important

Just as Judaism is made up of the written law (the Bible) and the oral law (the Talmud—although this, too, became written), so too the microcosm of the Sephardic experience is recorded through these two modes.

When it comes to Sephardic life cycles, the oral tradition is especially valuable: many life cycle customs were maintained by women who exclusively transmitted tradition orally across the generations. Through the oral history records in the Washington State Jewish Historical Society and interviews conducted by Albert Adatto, an Istanbul-native who helped to pioneer the field of Sephardic Studies as a graduate student at the University of Washington in the 1930s; and Aviva Ben-Ur, a professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst who served as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington in 2000-2001, we gain access into the inner lives of Sepharadim where these oral traditions manifested. In an effort to make our exhibit accessible, we have provided transcriptions for all recorded interviews.

For customs that fell more into the male domain, such as those that involved liturgy or rabbinic involvement, the written record is vital. Sephardic prayer books, compendiums of Jewish law, and handwritten manuscripts all provide insight into the variations in practice of life cycles throughout the Ottoman Empire and allow us to track how those customs changed in the United States.

Together, the written and oral records also raise a compelling question about the Ladino language. Our research suggested a close relationship between the decline of Ladino (both as a spoken language and as a written language in its various scripts) and the disappearance of certain Sephardic life cycle customs — a correlation that shows the inextricable relationship between language and culture. Yet even as Ladino has nearly disappeared as a spoken language, some uniquely Sephardic customs have survived. We invite you to consider our question with us: Why may cultural customs outlive the languages from which they originated?

Seattle is a microcosm of the Sephardic experience in America

![Congregation [Sephardic] Bikur Holim's letterhead Congregation [Sephardic] Bikur Holim's letterhead](http://jewishstudies.washington.edu/omeka/files/fullsize/892dd8aa6b5ebaabb98b9d5bd4b4a79c.jpg)

1920s letterhead from Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, a Sephardic synagogue in Seattle still operational today. Click to enlarge.

There is no denying that this exhibit is centered on Seattle. The artifacts in the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection at the University of Washington come mainly from local community members who entrusted our program with their personal treasures, and we have used these materials to build the stories around which this exhibit revolves. While some practices elaborated upon here may be particular to Seattle, they emerged out of a shared Ottoman Jewish world that began to fragment more than a century ago. The elements preserved and transformed in Seattle serve as a microcosm of the Ottoman Jewish experience and its worldwide echoes into the twenty-first century.