By Joseph Butwin

Professor Joseph Butwin shared this reflection with the students in his ENGL/JEW ST 357 Jewish-American Literature and Culture class on Monday, October 29, 2018, following the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh.

I am not a counsellor, a rabbi or a priest and I cannot come up with any consolation for the murder of 11 people and the wounding of others in Pittsburgh on Saturday. I say “people” and not Jews — though they were all Jewish people, shot because they were Jewish. I would rather not identify the victims of such a crime by separating them at death from the rest of humanity.

After a long sad day on Saturday, I reached back to the 17th century British poet and preacher, John Donne, for something like support. His topic in Meditation 17 are the church bells that traditionally toll for the dead and dying.

Perchance he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me and see my state may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that. The church is catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does belongs to all.

Later in the meditation, Donne continues:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefor never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Once in Denny Hall I was reading this passage, perhaps to explain the title of Hemingway’s novel — “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (1939) — when the carillon that used to ring from on top of that building broke into a peel of bells. I bowed to the class as if I had caused that confirmation of the text that I had chosen that afternoon. I was pleased.

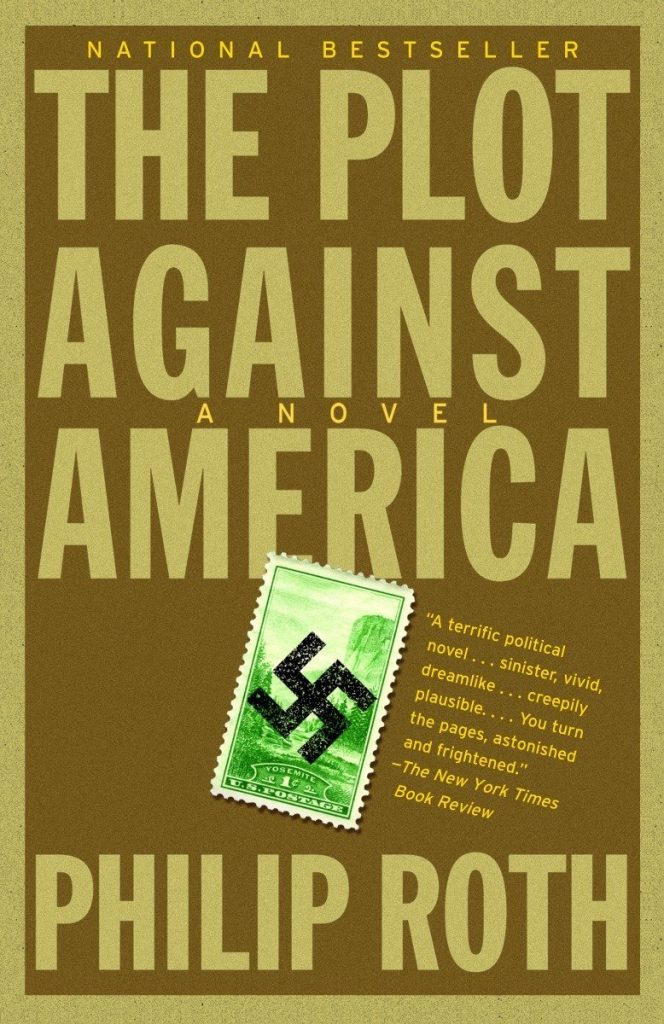

Now I am horrified by the apparent co-incidence of our reading of Philip Roth’s novel “The Plot Against America” (2004), which imagines an alternate-reality fascist America in the 1940s, and the mass-murder of Jews on Saturday. For one thing, I don’t think it’s a coincidence. There is something in our national life and in our history that permits these violent eruptions of hatred.

Now I am horrified by the apparent co-incidence of our reading of Philip Roth’s novel “The Plot Against America” (2004), which imagines an alternate-reality fascist America in the 1940s, and the mass-murder of Jews on Saturday. For one thing, I don’t think it’s a coincidence. There is something in our national life and in our history that permits these violent eruptions of hatred.

Shortly before Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life Synagogue in Squirrel Hill, a Jewish neighborhood in Pittsburgh, he tapped out what amounts to an explanation on his social media profile. It continues a thread that he began a few weeks ago when he posted a link to the website of HIAS — the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society — which was planning sabbath ceremonies on behalf of refugees around the country. He added a caption: “Why hello there HIAS! You like to bring in hostile invaders to dwell among us.” Then, a few hours before his attack, “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

Why HIAS? I suspect that few Americans recognize the acronym, which may be why some news media cut the first line out of Bowers’ last posting from their reports. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society began in 1881 as a response to the first phase of the mass migration of Jews from Czarist Russia. The organization continued its work even after American immigration laws prevented nearly as many arrivals after 1924; they supported later arrivals from the turbulent period immediately after World War II through the dispersal of Soviet Jews in the 1980s and ‘90s. During the last 20 years HIAS has “expanded our resettlement work to include assistance to non-Jewish refugees,” according to their website, which names more than a dozen danger zones around the world.

Why HIAS? I suspect that few Americans recognize the acronym, which may be why some news media cut the first line out of Bowers’ last posting from their reports. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society began in 1881 as a response to the first phase of the mass migration of Jews from Czarist Russia. The organization continued its work even after American immigration laws prevented nearly as many arrivals after 1924; they supported later arrivals from the turbulent period immediately after World War II through the dispersal of Soviet Jews in the 1980s and ‘90s. During the last 20 years HIAS has “expanded our resettlement work to include assistance to non-Jewish refugees,” according to their website, which names more than a dozen danger zones around the world.

HIAS writes on its website:

We understand better than anyone that hatred, bigotry, and xenophobia must be expressly prohibited in domestic and international law and that the right of persecuted people to seek and enjoy refugee status must be maintained. And because the right to refuge is a universal human right, HIAS is now dedicated to providing welcome, safety, and freedom to refugees of all faiths and ethnicities from all over the world.

We are, in other words, reading another chapter in what I have called the “Immigrant Debate” written across American history and literature. While this debate is not restricted to Jews, it seems perennially to lodge itself in anti-Semitism, for reasons that mostly defy my understanding.

I do not at all mean to find consolation or explanation in the words of a 17th century English, Christian clergyman who wrote his “Reflections” in a time when Jews were not welcome in his country. But I don’t mind reminding myself — and you — that a deadly assault on Jews is an assault on everyone. “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

The students in ENGL/JEW ST 357, Jewish-American Literature and Culture, have just finished reading Philip Roth’s “The Plot Against America” (2004), a political fantasy in which Nazi sympathizer Charles A. Lindbergh, running as a Republican under the banner of the America First movement, defeats Franklin Roosevelt and becomes President of the United States in 1940. He signs a peace treaty with Hitler. Anti-Jewish riots break out across the country. Before reading Roth, the students read a series of documents collected under the heading of “The Immigration Debate,” various texts running from 1880 to 1924, when frankly racist doctrine (under the polite heading of “Eugenics”) informed the restrictive Immigration Act of that year.

Joseph Butwin is an Associate Professor in the Department of English.

Further Reading

- The United States should embrace its legacy of compassion towards immigrants and refugees, not its history of xenophobia by Kathie Friedman-Kasaba (2018)

- The myth of Jewish immigration by Devin Naar (Jewish in Seattle, 2018)

- A Jewish historian’s plea for global refugees by Mika Ahuvia (2015)