March 21, 1965: Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel was among the civil rights leaders marching with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. from Selma Alabama to the state capitol in Montgomery.

By Rachel Grad

The past few years have witnessed anti-racist activism of a scale and frequency, perhaps not seen since the Civil Rights movement of the 60s. Here in Seattle, Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters have marched in the streets, rallied at political events, and lobbied for systemic change, such as an end to juvenile detention centers. As a scholar interested in histories of persecution, I expect to talk about racial inequality with my colleagues and my students. My research on representations of historical persecution in comics investigates cultural paradigms through which we come to know history. Some of these paradigms, such as narrative conventions and visual representations, implicitly normalize oppression. So I was honored when I was asked to lead a discussion on racial inequality at Seattle’s Temple de Hirsch Sinai this past November.

In his Yom Kippur sermon, Rabbi Aaron Meyer of Temple de Hirsch Sinai issued that challenge to the congregation, calling those in attendance to recognize the ways most American Jews experience white privilege. Many American Jews pride themselves on the idea that the Jewish community was instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1961, Martin Luther King, Jr spoke at Temple de Hirsch Sinai, and in 1965 Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel “marched arm-in-arm” with Dr. King in Selma.

[Editor’s note: to find out more about the history of Seattle’s Temple De Hirsch and the interfaith activism of its longtime leader, Rabbi Raphael Levin, visit John Larsen’s digital project here.]If Jewish leaders fought for racial equality, how can it be true that American Jews are guilty of white privilege? What responsibility do we share for twenty-first century racism? What can/should we do to combat inequality?

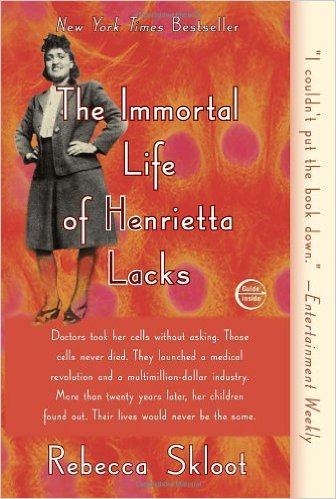

Reading about Henrietta Lacks

These are difficult questions. Throughout the month of October, Rabbi Meyer and I sent emails back and forth, discussing how to begin the conversation about our Jewish community’s role in issues of racial justice and equality. Ultimately we settled on hosting a book discussion and dinner. At 5pm on Sunday, November 8th, approximately 70 people gathered to discuss The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, to share ideas for further learning about social justice activism around race issues. We choose to read Skloot’s award-winning book, because it’s a story about the myriad levels of exploitation. As Skloot writes, “Henrietta was a black woman born of slavery and sharecropping who fled north for prosperity, only to have her cells used as tools by white scientists without her consent. It was a story of white selling black” (197). As a story of scientific discovery The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, emphasizes the lives of Mrs. Lacks and her children, lives impinged by racial inequalities in wealth, education and – ironically – also racial disparity in medical care.

When we gathered at De Hirsch to discuss Henrietta Lacks on November 8th, the discussion turned to the ways well-intentioned people can perpetuate racist stereotypes. For instance, while Rebecca Skloot’s motivations are undeniably to help the Lacks family, the way she describes them often echoes racist stereotypes of criminality, childishness, anger and simplicity. In the book’s prologue Skloot misrepresents the Lacks story as told in Jet, a black publication: “Jet said the family was angry – angry that Henrietta’s cells were being sold for twenty-five dollars a vial, and angry that articles had been published about the cells without their knowledge” (Skloot 5, my emphasis). The closest to describing anger the original Jet article titled, “Family Now Takes Pride in Mrs. Lacks’ Contribution” comes is by saying “The family was ruffled.” In fact, the article concludes with a direct quote from Henrietta’s son, “It’s good to know that someone can be helped by her cells . . . I am kind of happy.” (Original Jet article available via Google books at this link.)

When we gathered at De Hirsch to discuss Henrietta Lacks on November 8th, the discussion turned to the ways well-intentioned people can perpetuate racist stereotypes. For instance, while Rebecca Skloot’s motivations are undeniably to help the Lacks family, the way she describes them often echoes racist stereotypes of criminality, childishness, anger and simplicity. In the book’s prologue Skloot misrepresents the Lacks story as told in Jet, a black publication: “Jet said the family was angry – angry that Henrietta’s cells were being sold for twenty-five dollars a vial, and angry that articles had been published about the cells without their knowledge” (Skloot 5, my emphasis). The closest to describing anger the original Jet article titled, “Family Now Takes Pride in Mrs. Lacks’ Contribution” comes is by saying “The family was ruffled.” In fact, the article concludes with a direct quote from Henrietta’s son, “It’s good to know that someone can be helped by her cells . . . I am kind of happy.” (Original Jet article available via Google books at this link.)

That someone with a close relationship to the family and with good intentions (not to mention a team of editors), like Rebecca Skloot, implicitly reduces the complex emotions of a black family – including happiness and pride in their mother – to “anger,” means there is great work ahead for us as individuals and communally to avoid doing the same.

Learning to recognize bias

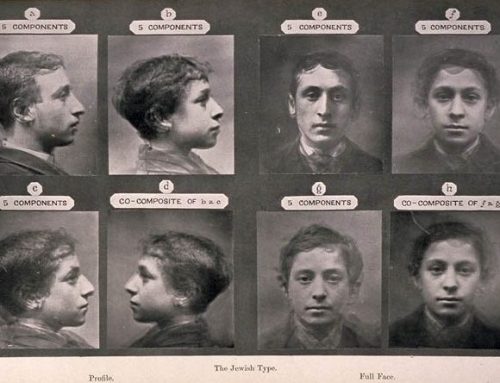

Systemic racism persists because from a young age, we learn to see the world through racist paradigms, and we don’t even know it. Racism is, so to speak, in the water. Narratives about the American dream and individual hard work are part of the problem. Like many American Jewish children, in Sunday school I was taught the names of Jewish heroes ranging from Sandy Koufax to Jonah Salk: in spite of the anti-Semitism they faced, these were individuals whom Jewish tradition had primed for hard work and, in turn, success. Or so the story went. This narrative perpetuates racial bias by implicitly denying cost of oppression and by ascribing individual success to ethnicity. To say, in effect, the Jews had it bad, but we overcame, is to assert that others should (be able to) follow our example and overcome their own oppressions. There’s nothing wrong with telling Jewish American success stories, but each lesson in what the Jewish community has endured, in the US and abroad, should acknowledge the material advantages that made ‘our successes’ possible, including access to whiteness. Those stories should not end with the Jewish community, but should also include parallel discriminations that affect other communities today.

The concept of “systemic racism” is a way of understanding injustice beyond the framework of bigotry. We acknowledge systemic racism when we are troubled by radically disproportionate incarceration, preventable deaths, graduation rates, and poverty, even as we know that the answer is nothing as simple as replacing hate with tolerance. The challenge for us as individuals and as a community is to recognize that while few among us are racist, most do hold implicit biases; to call ourselves out about them; and most importantly, to learn to see and narrate the world without them.

Rachel Graf is a Doctoral Candidate in English at the University of Washington. She is the 2015-2016 Philip Bernstein Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. At the UW Rachel has taught courses in literature and cultural studies. She is completing her dissertation about representations of historical persecution in graphic narrative. Interest in the ways cultural texts, including literature, film and other media can confirm and/or challenge systemic oppression motivates her scholarship and her teaching.

Rachel Graf is a Doctoral Candidate in English at the University of Washington. She is the 2015-2016 Philip Bernstein Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. At the UW Rachel has taught courses in literature and cultural studies. She is completing her dissertation about representations of historical persecution in graphic narrative. Interest in the ways cultural texts, including literature, film and other media can confirm and/or challenge systemic oppression motivates her scholarship and her teaching.

Early in your post, you object to Skloot’s misrepresentation of a story in Jet magazine, Skloot saying the story characterized the Lacks family as angry, when the story didn’t say that at all.

Then you go on to describe narratives of Jewish success as perpetuating racial bias “by implicitly denying cost of oppression [sic] and by ascribing individual success to ethnicity.”

You want Skloot to present only what was explicit in the article, yet you permit yourself to reach serious conclusions about what’s allegedly implicit in the articles about Jews. So what should it be? The same standards for you and Skloot, or different standards?