“Lady Lilith” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1867.

By Laura Lieber

On a Sabbath morning in the sixth century CE, in a Galilean synagogue, the community gathered for the reading of the weekly Torah portion, which began with Numbers 5:11, the trial of the accused adulteress (called, in Hebrew, a sotah):

If any man’s wife has strayed and betrayed him… or if a fit of jealousy comes over him and he is jealous about his wife although she has not defiled herself — that man shall bring his wife to the priest. … The priest shall take sacral water in an earthen vessel and, taking some of the earth that is on the floor of the Tabernacle, the priest shall put it into the water. … The priest shall put [the] curses down in writing and dissolve it into the water of bitterness. He is to make the woman drink the water of bitterness that induces the spell, so that the spell-inducing water may enter into her to bring on bitterness. If she has defiled herself by breaking faith with her husband, the spell-inducing water shall enter into her to bring on bitterness, so that her belly shall distend and her thigh shall sag; and the woman shall become a curse among her people.

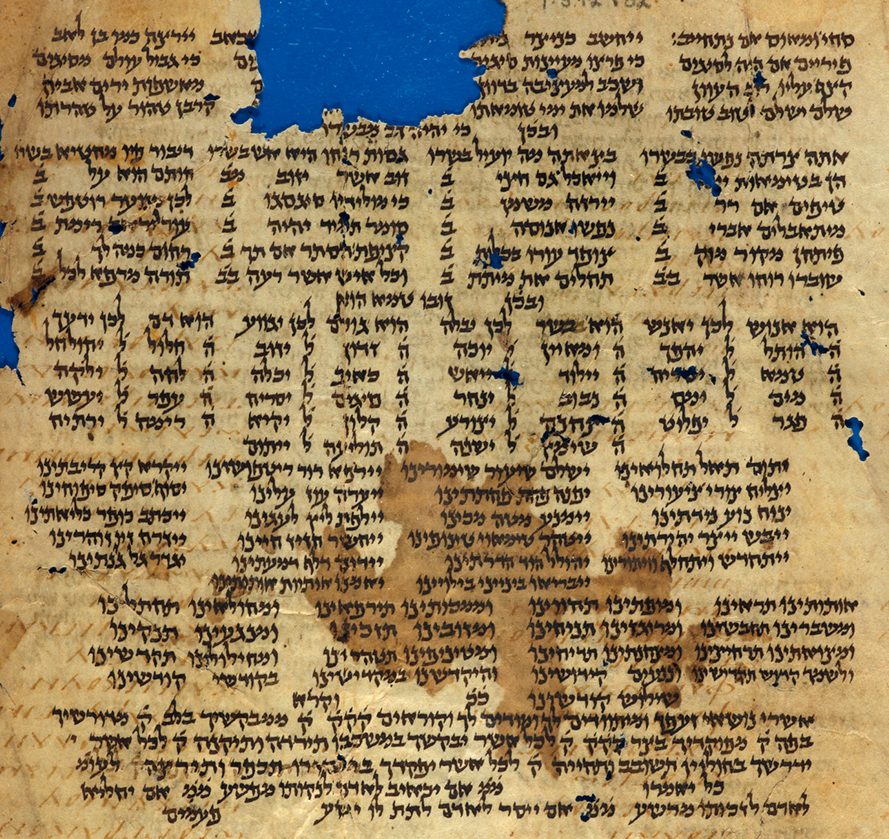

Yannai, one of the greatest synagogue poets — whose works were only recovered in the 19th century among the treasures of the Cairo Genizah — took this text as inspiration for his own composition, transforming the biblical scene into liturgical theater.

Original manuscript showing synagogue poetry written by Yannai. From the University of Cambridge Digital Library Cairo Genizah collection.

Indeed, while nowadays the synagogue prayerbook seems quite stable, in Yannai’s time the words of the prayers changed every week, and only the benedictions (“Blessed are You…”) were actually fixed. Synagogue poets wrote new prayer-texts each week (always concluding with the expected benedictions), at least in part to keep the service fresh and entertaining. These poems were called piyyutim, a term that comes from the Greek word poesis, also the root of the English words “poet” and “poetry.”

This poem does not merely retell the week’s Torah portion; instead, it recasts the private biblical ritual as a public exorcism of the human impulse to sin. Precisely because his stage is the public forum of the liturgy, Yannai amplifies and enacts the drama that the rabbis imagined in Mishnah Sotah, in which the trial of the accused woman and the consequences of the biblical ritual are depicted in graphic detail. In the hand of a synagogue poet, biblical law and rabbinic spectacle became ritual drama: a multisensory, immersive, even transformative experience connecting author, performer, and audience.

A world of magic and demonic danger

Ancient incantation bowl from Babylonia. Image via the Penn Museum.

Yannai, in concert with his congregation, leveraged the power of language in his poems to make and break spells. Indeed, as strange as it may seem to us today, Yannai lived in a world in which Jews — like non-Jews — believed in powerful forces, angelic and demonic, as evidenced by the popularity of amulets and magic incantation bowls throughout the Jewish world at this time. (Germ theory would no doubt have sounded just as outlandish to the ancients!)

The poem, performed within the ritually charged prayer service and replete with resonant biblical vocabulary, possessed intrinsic power. Challenged by the text of Numbers 5:11-31, Yannai offered his community potent conceptual magic, praying to contain and purge the dark impulses of humankind. This poem does not warn women against adultery so much as assure the community that God — moved by prayer — will keep them safe from themselves.

Poem 3 : Meshallesh (acrostic spells out “Yannai” –יניי )

י You know, O our Creator / our Evil Inclination

That it is our afflictor / crouched always at our sideנ The adulterer is named as “lacking of heart” / the adulteress, “wily-hearted”

But You, Creator of the heart / probe deeply the heart’s intentionsי O Yah, extinguish the coals / which burn within us

Renew the heart of flesh / and remove the heart of stoneי Bind the Evil Inclination / and no longer shall You have to watch over

The young women, should they play harlot / nor the brides, should they prove false

The magical elements of the poem appear most forcefully in Poems 3, 4, and 7A. Poem 3 opens on a forensic note, appealing to the omniscient deity to recall the flaws of human nature. In the final line, in language reminiscent of magical amulets of his era, Yannai petitions God to “bind the Evil Inclination (yetzer ha-ra)” — not a moral disposition, but a demonic force. And, indeed, in the very first line of Poem 3, the Evil Inclination is personified and uniquely bound to humanity, described as “our afflictor / crouched always at our side.”

This echoes Genesis 4:7: “sin crouches in the doorway,” which happens to be the place where Jews of Babylonia buried their magic bowls and where all Jews affix mezuzahs. (Doorways, as liminal spaces, are fraught; think about how traditionally a groom carries a bride across the threshold, and how in popular fiction vampires can’t enter unless invited in.)

Poem 4

From the time when that woman sinned through her hand

You lashed and bound the hands of womanShe is fire and her name is fire and she is likened to fire

Woman-from-man: She enflames the embers in the bosom of manShe sinned and brought into being the bitterness of death

Her sin was bitter as death / brazen is she, like deathNo one masters the day of his death

But all her pathways lead down to deathIn her eyes: death / at her feet: death

At her feet will dance the angel of deathUntil You swallow up Death and uproot the Evil Inclination

And remove the heart of stone from us

Incantation bowl showing Lilith.

Yannai develops the demonic subtext in Poem 4, where “that woman” (l. 1a) — Eve — becomes a death-bearing seductress whose hands must be “lashed and bound”; she is a Lilith figure — Lilith being the barren, child-killing demon whom tradition holds to be Adam’s first wife.

Throughout the poem, passion is linked to fire, a common symbol in erotic magic in Late Antiquity: “She is fire and her name is fire and she is likened to fire / Woman-from-man: She enflames the embers in the bosom of man.” “Woman” cannot but lead a man to a fiery death. By line 5, the imagery becomes explicitly demonic: “In her eyes: death! At her feet: death! / At her feet will dance the angel of death!”

Pleading for a remedy, the poet prays to God to “swallow up Death and bind the Evil Inclination.” Yannai’s language echoes the phrasing of magical bowls and amulets as he implores God to act in highly bodily, transparently physical ways: ingesting and lashing, uprooting and binding.

The poet does not merely seek a general exorcism; he details the process. Poem 7A offers a head-to-toe description of how the woman seduced her lover and a parallel head-to-toe infliction of comeuppance. The catalogue is comprehensive; no offending limb escapes mention.

Poem 7: First Rahit (full alphabetical acrostic)

She bound jewels upon her head

Thus in shame she unbound the hair of her head

She grew proud and fastened fancily the braids of her hair

Thus he judged she must hide her hair

She made herself pretty, for the sake of her sin

Thus she became stupid and ugly, because of her sin

She was insolent and brazen of face

Thus pale and green became her face

She soiled and defiled her flesh

Thus thin and sickly became her flesh

She concealed her perversity within her

Thus before the eyes of all it was revealed about her

She defied both curse and adjuration

Thus she succumbed to both curse and adjuration

She rebelled against that which was written for her

Thus her sins were revealed through a written text

She opened her thighs to the stranger

Thus her diminishment came with the wasting of her thighs

She called to the stranger and he embraced her belly

Thus decayed and bloated became her belly

She set her eye upon another

Thus she shall belong to neither her husband nor any other

Yannai, depicting the efficacy of these imagination-generated rituals, underscores God’s power to exorcise evil through human ritual using the Holy Name. Furthermore, the tightly parallel structure of the lines suggests that they were performed responsively in the synagogue, the aural performance thus underscoring the potency of the rhetorical structure: one voice adjures, and the other makes it so.

Throughout the poem, evocative binaries conjure vivid images: water and fire, binding and loosening, planting and uprooting, creation and un-creation. The demonic woman is “loose,” so she must be “bound,” language that evokes depictions of Lilith from magic bowls, with her hands tied and her pudenda exposed, accompanying incantatory texts promising to confine or expel her.

The act of sex, which should have been procreative, becomes destructive; she who ought to be a genetrix, a miraculous mother-of-life, instead decomposes in graphic detail. She is uncreated: her thighs rot, her uterus falls out, her eyes bulge, her fingernails fall off, and her body gives way.

Queen of the Night relief from 18th century BCE Babylonia, possibly inspired by Lilith.

In restoring the adulteress to the primordial ooze, the poet works his own kind of disturbing magical spell on his listeners. His rhetoric — deploying graphic and titillating visual imagery, still potent today and unsettling to imagine as part of synagogue prayer, and presumably reinforced by the speaker’s body language — makes an imaginary scene visible and audible to his congregation (male and female), collapsing the boundaries between “then” and “now,” as the community at prayer morphs into bystanders to and beneficiaries of the punishment of “that woman,” even as they pray that such impulses be expelled from their own midst.

Making sense of the sotah today

The trial of the accused adulteress (sotah) is not a biblical passage that resonates with modern readers. It is a stark reminder of the deeply patriarchal (and deeply heteronormative) nature of Israelite society at the time, and takes us into the least-healthy parts of the human (and of the male) psyche.

And yet, precisely because it is part of the Torah, Jews in the synagogue could not (and cannot) look away; Numbers 5 is bound to come up as a Torah reading on a regular basis. But perhaps Yannai’s community didn’t want to look away. This poem was an imagined spectacle in an age defined by spectacle, and the poet reads the biblical magical ritual in light of the social norms and magical practices of his own day.

He does not solve the problem of God imposing such a the troubling ritual on the Israelites — and by extension on all who regard the Torah as in some sense sacred — but he offers us a window into his world: a world where demonic forces and dark dangers lurked, but where potent words and powerful imagination could protect the people. Poetically.

Laura S. Lieber is Professor of Religious Studies and Classics at Duke University, where she directs the Center for Jewish Studies and the Center for Late Ancient Studies.

Laura S. Lieber is Professor of Religious Studies and Classics at Duke University, where she directs the Center for Jewish Studies and the Center for Late Ancient Studies.

This is a fascinating study, especially since my search here was conversations and events around ancient magic–at the UW. What’s been interesting for me, studying the history of magic–particularly as it relates to design–are the ancient Jewish renderings of these conversations–what they mean then, what they mean now. An attractively articulate and easy to walk-through article–really helpful. Thank you.

Thank you!!