Dr. Anat Mooreville is this year’s Hazel D. Cole Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Editor’s note: The Hazel D. Cole Fellowship in Jewish Studies is a prestigious position offered to doctoral and post-doctoral students. This year, we welcomed Anat Mooreville, a recent Ph.D. in history at UCLA. Dr. Mooreville will share her research at a March 8th talk, “‘Dr. Loewenstein, I Presume?’: Israeli Eye Aid to Africa, 1959-1973.” Find out more and register here for this event, which is part of our “Israel Studies Today” lecture series.

We recently caught up with Dr. Mooreville and learned more about her fascinating research into the medical history of the Middle East, which she will be showcasing as part of her Spring Quarter course on global health. Read on to find out more about this talented historian!

Hannah Pressman: Congratulations on becoming Dr. Mooreville this past fall! Please share a little about your dissertation research. How did you make your way to this topic?

Anat Moorevile: At the turn of the century, the infectious eye disease trachoma was ubiquitous in practically every country in the world: whether in the United States’ “trachoma belt” through the Appalachian mountains, the Jewish ghetto in Amsterdam, or villages along the Egyptian delta. Its prevalence led to the founding of the first eye hospitals in Europe and helped to launch ophthalmology as a specialty. Although trachoma is still cited as the leading cause of preventable blindness, it has all but been erased from public consciousness.

My dissertation, “Oculists in the Orient: A History of Trachoma, Zionism, and Global Health, 1882-1973” (which I am turning into my first book project), examined how a wide range of actors—including physicians, scientists, hospitals, aid organizations, governments, and the public—defined and deemed eye health salient from political, economic, scientific and cultural perspectives in Ottoman and Mandate Palestine and Israel from the late nineteenth century through the 1970s. Rather than confined to a single geographic space, tracking Jewish interest in trachoma mirrors important shifts in geopolitical developments, highlighting new areas of the globe with each decade: German medical and orientalist scholarship in the late nineteenth century, the rise of the American-sponsored Hadassah Medical Organization in British Mandate Palestine, decolonizing North Africa in the 1950s, and sub-Saharan Africa in the postcolonial era.

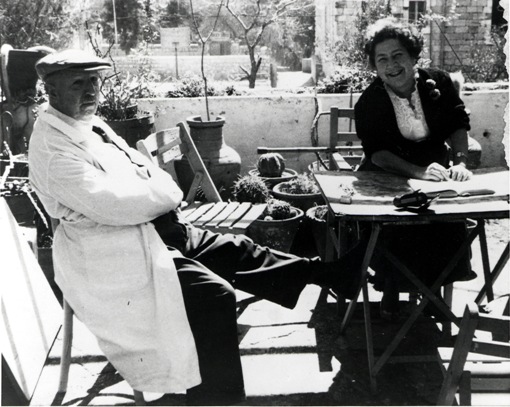

The Lema’an Zion eye clinic, ca. 1913. Photo credit: Hadassah.

I first became interested in trachoma after visiting the Ticho House, which is a beautiful Ottoman-era house across the street from the Zion Square in Jerusalem. The first floor had been the eye clinic of Dr. Abraham Ticho (1883-1960), and the second floor was where he lived with his wife, artist Anna Ticho. Now it serves as a lovely café and small art museum. I stopped by to get a cappuccino, but instead found myself captivated by the photographs of Ticho and his overcrowded waiting room: he developed an imminent medical reputation treating Jewish and Arab patients, including Emir Abdullah, the first King of Jordan; Haj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem; and various other sheikhs from Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iraq, and Egypt.

Supposedly “Dr. Ticho” became the generic name for any eye doctor. His name has retained some sticking power in Israeli popular culture in the modern Hebrew idiom “mi-yemei Ticho” (“from the days of Ticho”), figuratively meaning from the British Mandate days.

Two questions from this experience spurred the beginnings of my research: Why did Ticho’s clinic come to signify an oasis of Jewish-Arab coexistence? How does an ophthalmologist become a celebrity in the first place?

Dr. Abraham Ticho and his wife, the artist Anna Ticho.

HP: Who are some scholars or books that have influenced you?

AM: One of the books about the writing of history that I’ve found valuable is John Lewis Gaddis’ The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past. I came to history through literature, so I always appreciate books that either tell a good story or experiment with the boundaries of historical writing and thinking, including Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, or Warwick Anderson’s The Collectors of Lost Souls: Turning Kuru Scientists into Whitemen.

HP: What will be the focus of your campus talk on March 8th?

AM: My talk will be about Israel’s eye aid program to sub-Saharan Africa in the 1960s. Although it is not as well remembered now, Israel made a tremendous diplomatic push in the 1960s to befriend African nations. My lecture will be about how and why ophthalmology became Israel’s largest medical aid endeavor, and in so doing, make a larger case about why following Jewish and Israeli medical networks neglected in the history of medicine creates new genealogies of global health.

HP: Tell us a little about your Spring Quarter course.

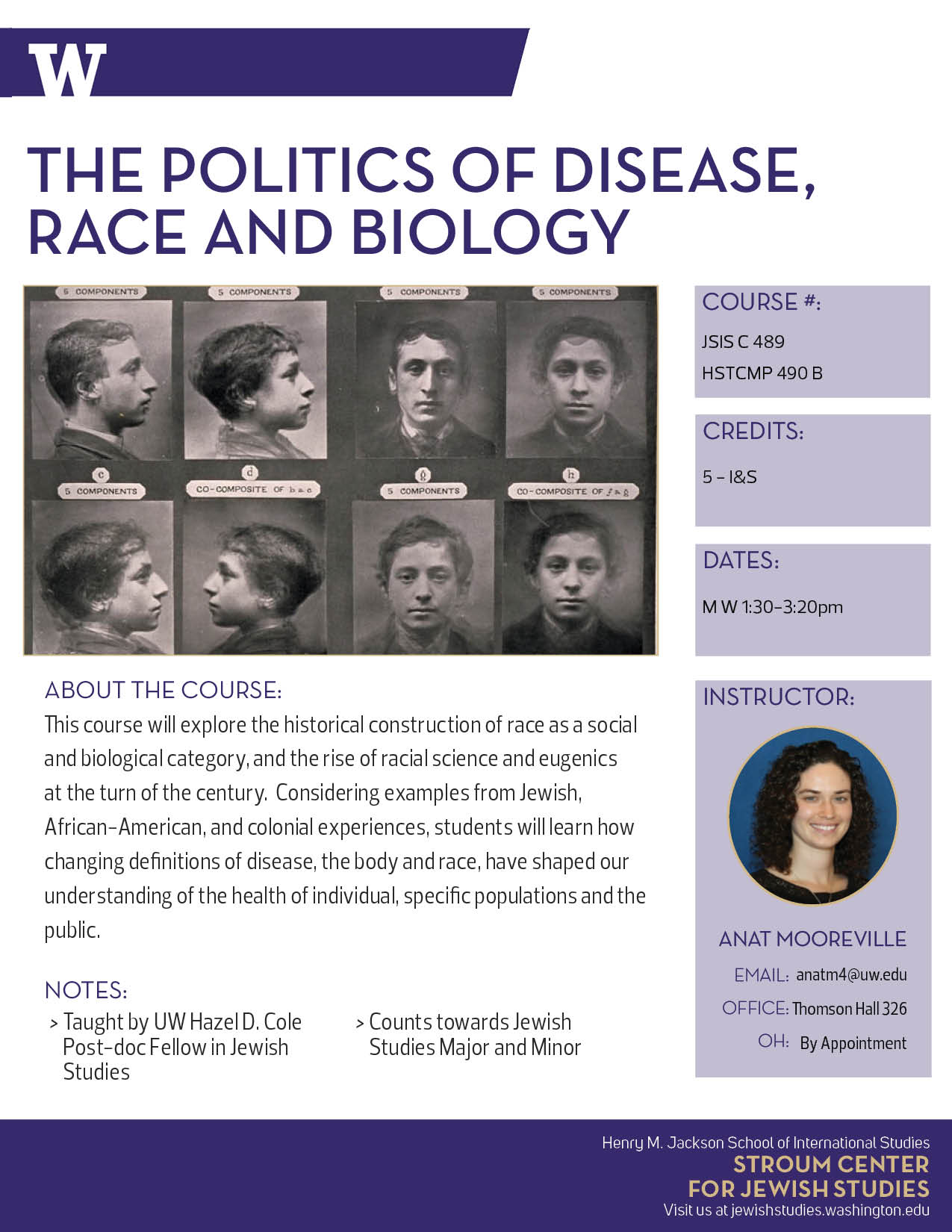

AM: The course I will teach in the spring, “The Politics of Disease, Race, and Biology”

HP: What have you enjoyed exploring so far in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest?

AM: My favorite thing to do in Seattle on a sunny day is to ride my bike down on Alki Beach. I also enjoy going to the Ballard Farmers Market on Sundays, or exploring Washington’s beautiful parks and hiking trails.

HP: Anything else to you’d like to share with our readers?

AM: I am really interested in urban planning and policy. In Los Angeles, I supported several civic initiatives that engaged with and improved city life, including CicLAvia, Los Angeles Walks, and Design East of La Brea.

For Further Exploration

Here is the flyer for Dr. Mooreville’s Spring Quarter course. You can register here starting Feb. 12th!

Interesting article on Dr. Moorville’s explanation of how she became involved in her specialty.