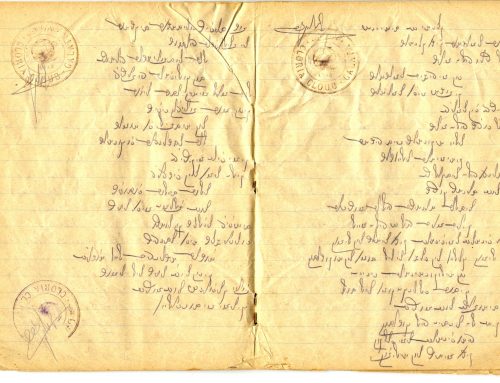

A 2013 Jerusalem snowstorm as seen from the balcony of the apartment where Anat Mooreville’s grandparents live. Photo by Anat Mooreville.

“Beans are the meat of peasants,” Hana explained, as she ladled some steamy kidney bean soup into my bowl on her dining room table. She cooks slowly, with precision, and an eye towards aesthetics. The reddish-brown liquid is brightened by small pieces of carrot, red pepper, and fresh parsley. Nothing here is new. Black spots speckle almost all of her chipped enamel pots. The apartment, recently built when she moved in 1966, has not been renovated. The furniture, however, has been extremely well maintained for the past sixty years, and is now back in fashion: tinted glass chandelier shades with raised polka dots, an antique radio cabinet, wooden Danish Modern stacking tables. “It’s not bourgeois food, but that does not bother me,” she continued in Hebrew, as she placed the blue trimmed bowl on a plastic plate, and passed it to me across the table.

I have called my maternal grandparents by their first names, Hana and Iancu, for as long as I can remember. I never thought this odd until I heard my Israeli-born cousin call them Savta and Saba, the Hebrew words for grandmother and grandfather. I asked Hana for clarification. She answered, “I thought it would create intimacy if you called me by my first name. We were so far apart.”

The four-room apartment is located on the western edges of Jerusalem. From the balcony on the fifth floor you can see the tops of pine trees dotting the Jerusalem Forest to the right, and the rest of Ha’arazim Street curving up the hill to Herzl Boulevard on the left. Most of these apartment buildings were built in the fifties and sixties when mass immigration to Israel created an urgent and quick need for housing. My grandparents could not afford to learn how to drive; instead, they paid the mortgage. My mother shared a bedroom with her brother throughout high school and into her twenties. Their wheelchair-bound grandmother, Miriam, commanded the third bedroom, the only one with a television set. Hana told me they would all crowd in to watch on special occasions, like Israeli Independence Day, to see the festivities happening a few short miles downtown by Zion Square.

We speak only Hebrew to each other. Hana also knows Romanian, German, French, Yiddish and English, but her English is more of the reading variety than the spoken one. She has said more than once that when I speak English it sounds like Chinese. I speak quickly, like most East Coasters, with words running up against each other, but it’s not that; she’s just not used to hearing the language. And so, Hebrew is our imperfect compromise. She imitates my American accent in jest, even though her own Hebrew grammar is often in error. Mostly, she confuses masculine and feminine verb conjugations. Iancu, ever so gently, will sometimes softly correct her and she’ll boldly answer back, “I’m sorry, but my culture is not in this language.”

My culture is also not in Hebrew. I grew up in Philadelphia, a first-generation American, whose parents escaped Communist Romania: Hana, Iancu and my mother moved to Israel fourteen years after applying for a visa, and an happenstance meeting with an American couple in a Bucharest park led my paternal grandparents and father to the United States. Although the opportunity for a multilingual upbringing was possible, my parents considered Romanian useless, and my mother did not want to speak to me in Hebrew, a language my father did not understand. Whatever Hebrew I know is from the repetition of daily classes in a K-12 day school education, drilled so early and often that I don’t remember a time when I could not recite past, present and future verb tenses. By senior year, I was tested on poems by Tchernichovsky and Amichai—and as beautiful as they were—my vocabulary lists were more often than not filled with words irrelevant to common street exchanges.

My real Hebrew conversational skills, then, come from talking to Hana and Iancu around their dining table. They were often patient with me when I needed to grope for a word, and they themselves spoke slowly in a simplified lexicon. As my research in Israeli history brought me frequently to Jerusalem archives, I was able to spend extended amounts of time with them as an adult. Some conversations were heated over political or emotional matters, and at times we found ourselves at a literal loss for words: Hana would head over to her Romanian-Hebrew dictionary in the study, while I would simmer in my frustration that I lacked the facility for nuance and depth in Hebrew that I had in English.

Could I know my grandparents in Hebrew? Could they know me?

This gulf between us was one both of language and of culture. My mother had to clue me in on the correct way to act around my grandparents, to Romanian mores of behavior and communication. But without Hebrew, I don’t know if I would have been able to have those conversations—as tough as they sometimes were—with Hana and Iancu about their lives and experiences. Therefore, as much as Hebrew could be a barrier, it has also been an incredible bridge to my grandparents and their world. Every time I visit their apartment, Hana squeezes my hand and tells me, “Don’t forget that you have a home in Jerusalem.” That home, of course, is in their hearts: a place beyond language.

Anat Mooreville is the Hazel D. Cole Postdoctoral Fellow in the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle. Her research concentrates on Jewish history in the Middle East and North Africa, the history of medicine and science, and Israeli history. Her forthcoming article, “Eyeing Africa: The Politics of Israeli Ocular Expertise and International Aid, 1959-1973,” will appear in the Spring/Summer 2016 issue of Jewish Social Studies.

Links for Further Exploration

- Meet Anat Mooreville, This Year’s Cole Fellow in Jewish Studies

- How We Connect to Hebrew – Blog Series for “Hebrew and the Humanities” Symposium