By Makena Mezistrano

My favorite Ladino refran, or proverb, offers a reminder that’s particularly apt for the past year: El mundo se manea ma no kaye — “the world shakes, but does not fall.” It has been the refrain in my head throughout the changes we’ve all experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, reminding me that the hardest challenges require creative solutions, and to remain open to opportunities even when the possibilities seem limited.

When spare rooms in our homes became offices and Zoom calls replaced lunch meetings or walks through the quad, our Ladino novels, newspapers, biblical commentaries, and many other books and artifacts on the University of Washington campus felt far away. In the new pandemic era we turned to digitized pages to recall the stacks of cultural heritage preserved in our offices. This “virtual bookshelf,” constituting over 140,000 images of published Ladino material, afforded us the unforeseen opportunity to make important strides in the development of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection during this challenging year.

While the University of Washington’s shift to remote operations greatly impacted all departments, it had significant implications for the UW Libraries. Catalogers could no longer spend time in the physical stacks organizing and developing collections, and most archival management was halted. The focus turned toward already digitized collections; thankfully, due largely in part to the work of Ty Alhadeff, the program’s former research coordinator, our repository of 480 Ladino books was scanned and awaiting the expertise and assistance of our university librarians.

“The fact that these books were already digitized was quite lucky,” said Ben Riesenberg, a Metadata Librarian in the Cataloging and Metadata Services unit of the UW Libraries, who has taken the lead in supporting the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. “Much of my work already took place online prior to work-from-home, but the ability to focus on the digital collections metadata design process at a time when colleagues and collaborators have more availability has been very helpful.”

We are thrilled to share three important milestones, each of which brings us increasingly closer to launching the world’s largest, open-access, online library of Ladino texts, audio, and archival materials.

The first published metadata application profile for a Ladino library

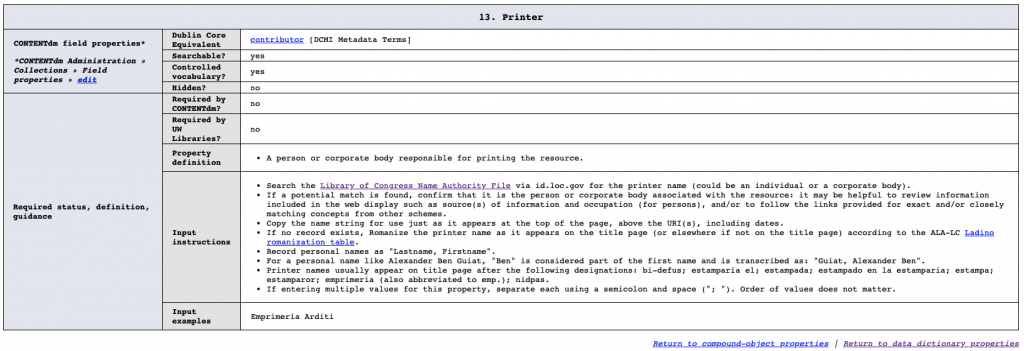

In order for students, scholars, and members of the public to find the Ladino books in our collection, we have to create descriptive metadata. These are essentially categories or fields (also known as properties) that hold information about the books — their titles, authors, languages, the time and place in which they were published, and much more. We want you to be able to find every Ladino book from Izmir in our collection by searching for “Izmir,” for instance, which is only possible through the creation of robust metadata. The field titles and instructions for how to input specific data into these fields, among other particulars, are contained in a document known as a metadata application profile. Creating such a document will elevate the professionalism and legitimacy of our collection to that of other established digital libraries.

Portion of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection metadata application profile. This snapshot captures the “printer” field, a new property created specifically for this collection.

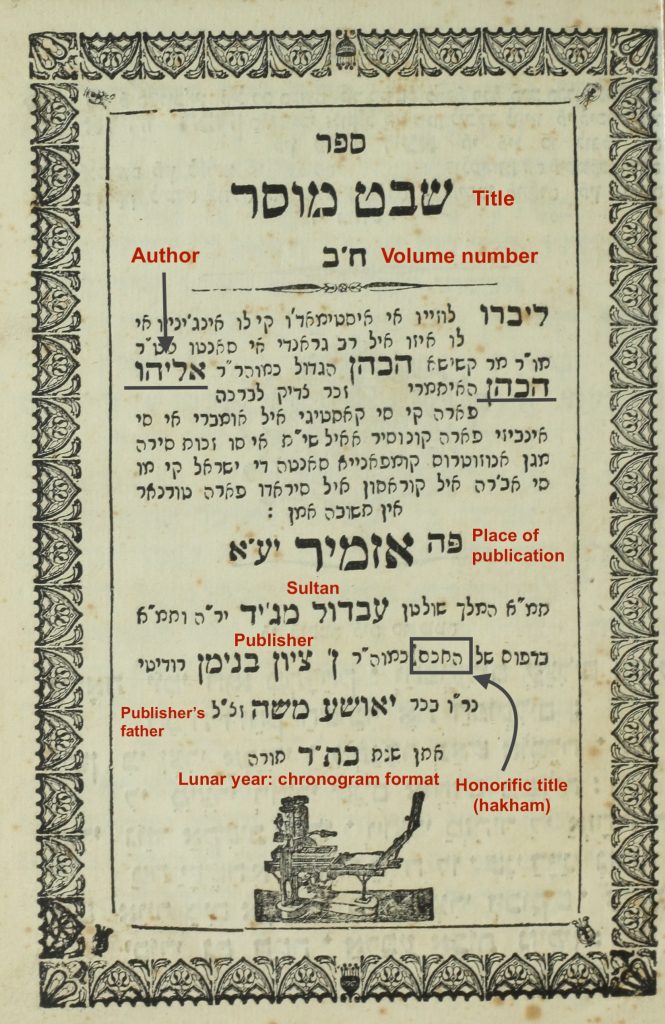

As I have shared in a previous essay, current library standards are not always appropriate or sufficient for describing Ladino texts. Producing these books was a collaborative effort that sometimes involved as many as five distinct roles (author, translator, editor, publisher, printer), which are not easily contained in the singular, widely used metadata field of “creator.” The books themselves recognize all these creative contributions, but descriptive metadata in other digital Ladino libraries often obscures some of this critical information. Our effort to address these informational gaps resulted in the creation of fourteen new metadata categories unique to the world of Ladino book production, which contribute to the twenty-six total metadata categories for our collection.

Annotated title page for the Ladino Shevet Musar (ST00390, courtesy Richard Adatto). These annotations give a sense of the considerations involved in creating metadata for Ladino books.

“It’s been rare in my experience to collaborate with a collection owner who is so interested in and engaged with metadata,” said Riesenberg. “Collaboration with Sephardic Studies Program staff has been invaluable in planning for this collection. Their subject-area expertise and input will allow for descriptive work that serves the scholarly community by capturing unique characteristics of these resources.”

Translating the world of Ladino publishing into data fields involved numerous considerations; we even made certain sacrifices in order to adhere to universal library standards so that our collection could communicate with other digital Ladino libraries. Surprisingly, one of our most challenging questions involved determining how to capture provenance (a record of ownership for a given item) — a descriptive element which, we learned, is somewhat uncommon beyond archival collections, and is further complicated in our case due to the multiple hands through which a Ladino book may have passed before arriving to us.

Publicly acknowledging the community members who contributed these books to the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection was non-negotiable; it is only through this grassroots effort that our library came to fruition. There was also a functional benefit: when the library is live, all books will be able to be sorted by donor or lender (provenance). This kind of organization will illustrate the important pockets of preservation maintained throughout the Seattle Sephardic community, and how these scattered, personal collections are coalescing online.

When it is published at the end of this summer, our metadata application profile will be the first of its kind to specifically treat a repository of Ladino books. We hope this will offer a model not only for Judaica librarianship, but for any text collection that requires a departure from “traditional” library standards to improve the public’s understanding of the communities from which those collections originate.

High quality scans

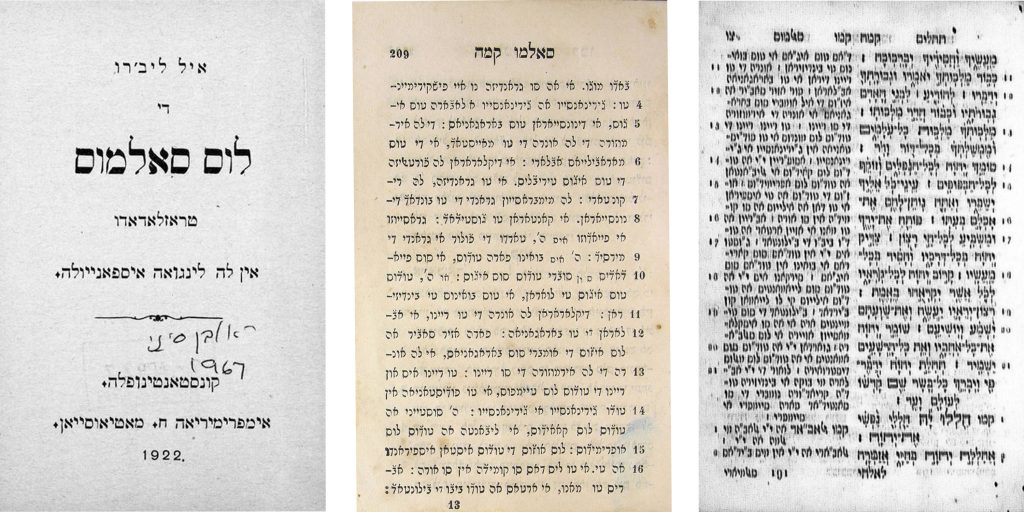

While many digital Ladino book collections rely on black and white microfilm images created several decades ago, our library will continue to feature color images of all Ladino texts. This will offer a digital reading experience that most closely resembles viewing the physical book.

Digitized versions of Tehilim (Psalms) in Ladino. Left to right: Los salmos, Library of Congress; Tehilim en Ladino (ST00261, courtesy Elazar Behar); Psalms in Ladino, Harvard University Library.

Although some of these books were scanned several years ago, all the images — around 140,000 — had to be post-processed before being uploaded online. This involved cropping, tinting, and straightening the images to produce a cohesive look and feel throughout a single text, and to ensure that the pages were legible. At the beginning of June, we completed the post-processing review for our 480 Ladino titles — a critical step in preparing the books for upload to the UW Libraries.

New collaborations

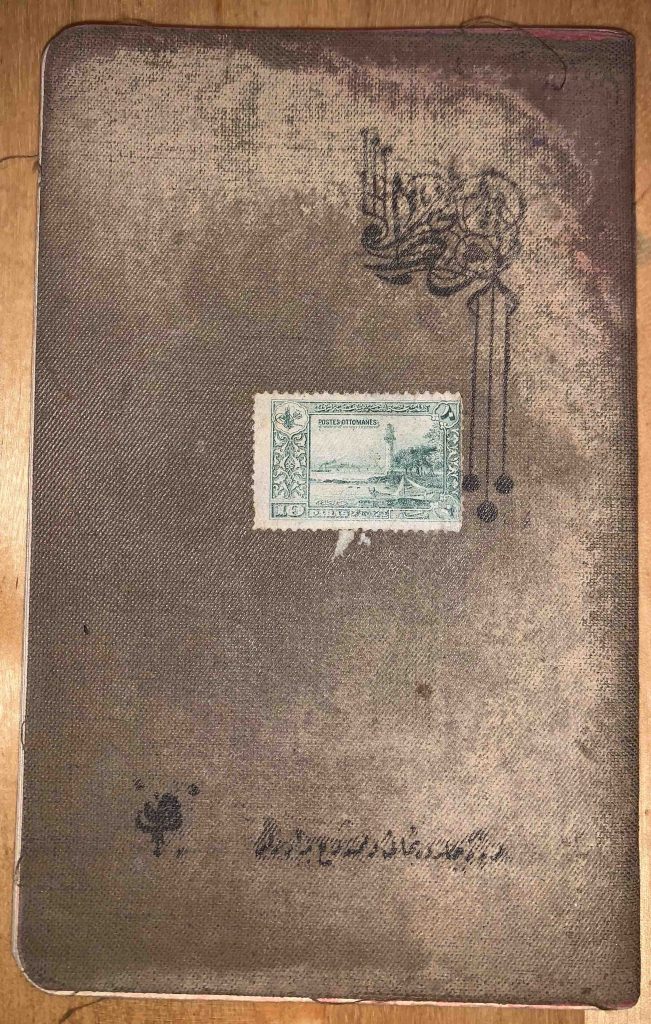

Cover of one of six Ottoman Turkish journals kept by Jewish officer Salomon Habib during World War I (courtesy his grandson and great-grandson, Shlomo and Tom Haviv, respectively).

Improving our digital infrastructure has also opened new and exciting opportunities for collaborations with scholars from around the country as we broaden the scope of our collection beyond Ladino books. We will be expanding the Benmayor Collection of Sephardic Ballads over the summer to include Rina Benmayor’s (Professor Emerita, California State University Monterey Bay) field recordings of Ladino songs from Los Angeles, which will complement the 140 Seattle recordings already online.

“The ballads I collected and my studies of them were published in Spain, in Spanish, but the recordings still sat in a shoebox in my study, for decades — that is, until the creation of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection,” said Benmayor. “Through a wonderful and extensive collaboration, the Seattle portion of my collection was digitized, catalogued, and made available online. It is reassuring to know that this collection will be completed with the addition of the Los Angeles ballads, and will exist in a public space for many generations, thanks to the vision, expertise, and professionalism that the Sephardic Studies Program embodies and maintains.”

Benmayor has also been collaborating with Dalia Kandiyoti (Associate Professor of English at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York) on an oral history project that documents nearly seventy individual reflections about Spain and Portugal’s recent citizenship offers for those who can prove Sephardic ancestry. The subjects — practicing Jews, Sephardic identifying, or neither — applied from the United States, Turkey, Israel, Venezuela, Argentina, the United Kingdom, and more. Their stories — told in English, Spanish, Turkish, and Portuguese — consider citizenship, identity, nationality, and the boundaries of each today. This cache of interviews will also become part of our digital library in the coming months.

“From the beginning, Dalia and I felt that this material belonged in a prominent, professional, and active repository in the field,” said Benmayor. “The Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, in conjunction with the University of Washington Libraries, was our preferred and only choice, given the breadth and depth of their collections, their expertise, and track record in elevating Sephardic studies to a new height. We knew that our material would be understood, curated, and made widely accessible.”

Several individuals have also approached us to assist with translation and preservation of important family documents, some of which will be major contributions to the fields of Jewish and Ottoman studies. These include a Ladino journal from Salonica, which includes original songs by the author; a series of six notebooks in Ottoman Turkish kept by a Jewish officer in the Ottoman army during World War I; and a collection of photographs and postcards in soletreo, the Sephardic Hebrew cursive script used to write Ladino, from pre-war Salonica.

These contributions — from published Ladino books to audio recordings to archival documents — are coming together to form the next phase in our Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. Our library infrastructure will enable many of these artifacts and projects to attain visibility for the very first time. The Ladino books in particular have been cherished and preserved through generations of migration between empires and nation-states, and have survived transatlantic journeys. Some have not been read or studied in decades; for some, it has been centuries since they have even been seen. An expanded virtual library, open and accessible to all, is the best way to share these pieces of Sephardic culture and memory with the world. We can’t wait for you to see it.

We thank our colleagues at the UW Libraries for their unparalleled support throughout this past year: Theo Gerontakos, Anne Graham, Ann Lally, Ben Riesenberg, and the members of the UW Libraries Metadata Implementation Group.

I look forward to the Sefardi collection.