Three title pages of various Ladino books from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. (Courtesy Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation)

By Makena Mezistrano

In 1792, Salonican brothers Shabetai and Hayim Nehama decided to try their hand at the melekhet ha-kodesh — the holy work — and opened a printing press. Their books were printed in the lashon ha-kodesh — the Hebrew language that elevated the printing profession to a sacred service — and they mostly produced works on religious topics. The brothers also printed books in Ladino so that these important texts could be read and enjoyed by the masses.

The development of Jewish printing houses in the Ottoman Empire

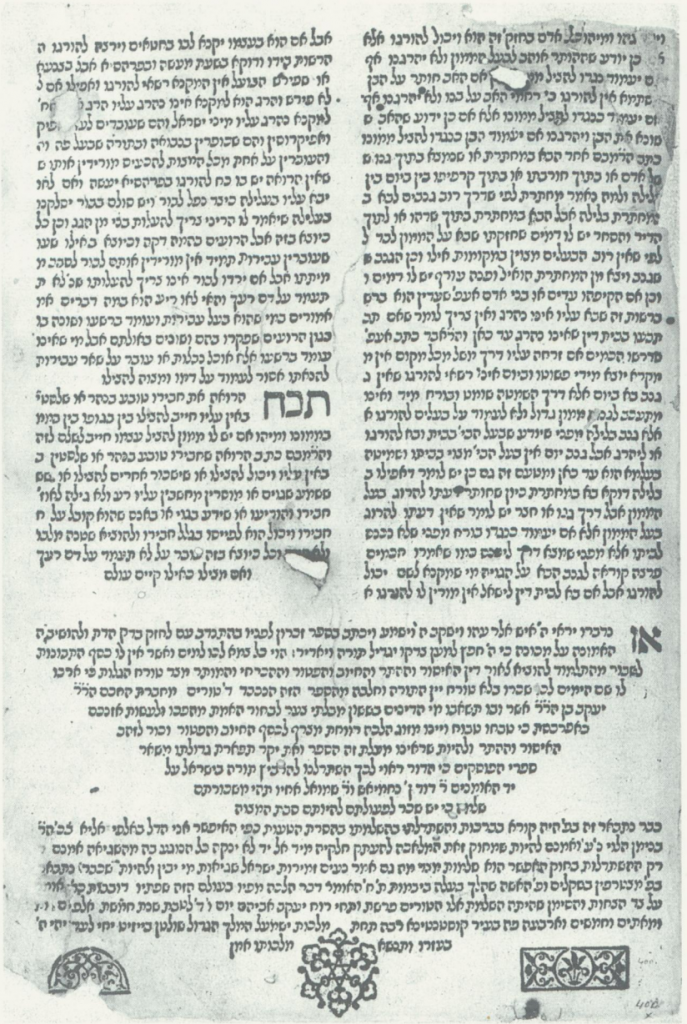

Page from the Arba’a Turim printed in Istanbul (1493). Reproduced in The British Library Journal, 1996.

The Hebrew language was not the only thing that imbued printing in the Ottoman Empire with a Jewish character. For nearly 300 years, Jews played a primary role in book production in the Ottoman world: The very first book in any language to be produced in the Ottoman Empire was the Hebrew Arba’a Turim, a compendium of Jewish law printed in Istanbul in 1493 — just one year after the Spanish Expulsion. While Greeks and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire established their own printing houses nearly a century later, Muslim printing presses did not emerge until the eighteenth century. Up to that point, Muslim authorities opposed printing religious texts because to print them would profane them; for the scribes who wrote them, it would undermine their craft.

Less than 20 years after the first book was printed in the Ottoman Empire, a Jewish printing house opened in Salonica, which became one of the most important cities for Jewish printing in the world; however, by the time the Nehama brothers opened their printing press in 1792, Salonica was experiencing a relative lull in Jewish printing. The Nehama brothers undertook their enterprise nonetheless and formed an important partnership with Sa’adi Ashkenazi a-Levi.

Sa’adi’s crucial contribution to the partnership was the Hebrew letter molds that his grandfather, Besal’el, had brought to Salonica from his own printing press in Amsterdam in 1731. It was not uncommon for émigrés from the Iberian Peninsula to Salonica, and elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire, to preserve their craft in their new Ottoman homes: Indeed, those Hebrew letters used to print the first book in the Ottoman Empire were imported from Spain.

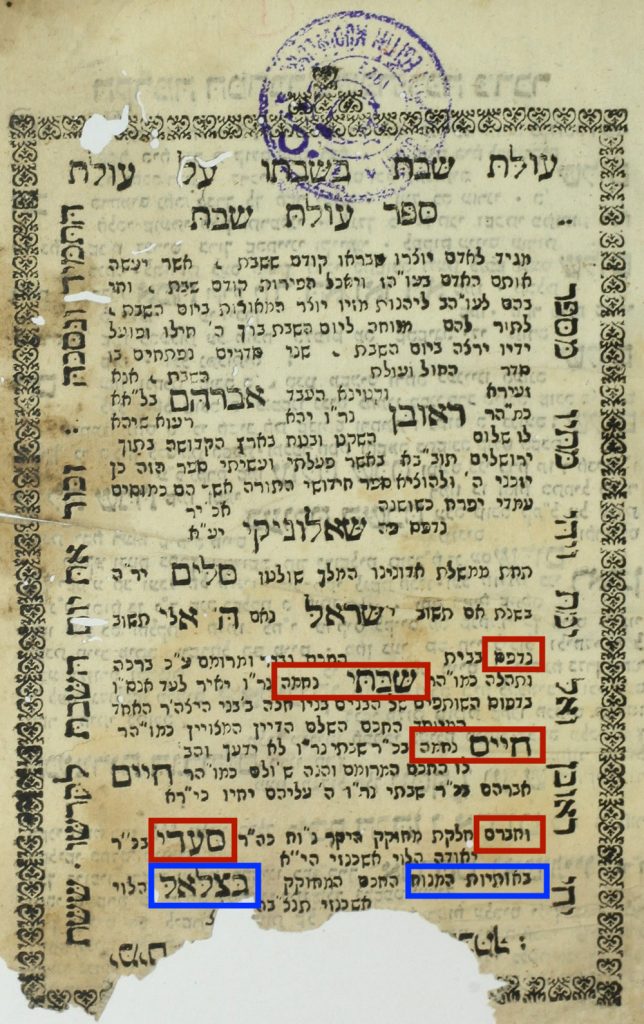

Title page for the Ladino book Sefer Olat Shabbat (ST00344). Partners Shabetai, Hayim, and Sa’adi are boxed in red; credit for the letters of Besal’el a-Levi Ashkenazi [sic] are boxed in blue. (Courtesy Richard Adatto)

Ladino books recognized multiple contributors

While it is impossible to know how many copies of Olat Shabbat were printed and circulated in Salonica, only five copies are known to exist today. And although Olat Shabbat was published on the cusp of Salonica’s printing boom, it is impossible to know just how significant that period of Jewish printing was due to the absence of any comprehensive bibliography of Jewish books printed in the Ottoman Empire.

One thing, however, is certain: without the collaboration between the Nehama brothers and Sa’adi a-Levi, Olat Shabbat would not have come to fruition. The book itself concedes as much: both Nehama brothers, as well as Sa’adi, are credited by name as partners in printing the work on its title page. Even the Hebrew letter molds receive a byline: under Sa’adi’s name appears credit for “the letters [oti’ot] of the deceased…Besal’el a-Levi Ashkenazi [name as printed].”

Discrepancies between Ladino books and library catalog entries

Today, rare Ladino books like Olat Shabbat are often difficult for most people to physically access and are tucked away in special, protective boxes and sealed behind locked doors. This is the irony of protecting important books: fewer people get to read them, let alone ever see them. When physical access is limited, certain digital tools enable researchers to access these texts. Unfortunately, the content of Ladino title pages, and the information they offer scholars, has been gradually obscured in the very place where it should be the most accessible: the library catalog.

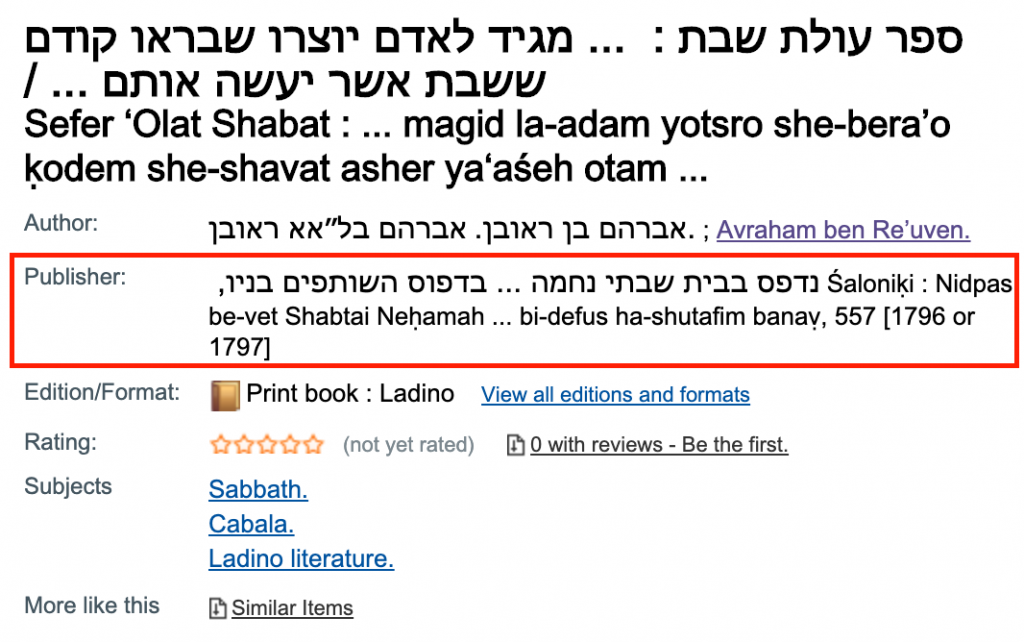

Catalog entry on WorldCat for Olat Shabbat. Here, two out of the three printers, who are mentioned on the book’s title page, are omitted.

In the catalog entry for Olat Shabbat on WorldCat, the largest consolidated digital library catalog in the world, two of Olat Shabbat’s publishers are missing: neither Hayim Nehama nor Sa’adi a-Levi are attributed any credit for their roles in producing the work. Instead, in the entry’s ‘Publisher’ field, only Shabetai Nehama is named.

In a single catalog entry, the company formed between two brothers that made producing this book possible — a venture only accomplished by the hand-me-down tools contributed by their partner — has been erased.

Why might these discrepancies exist?

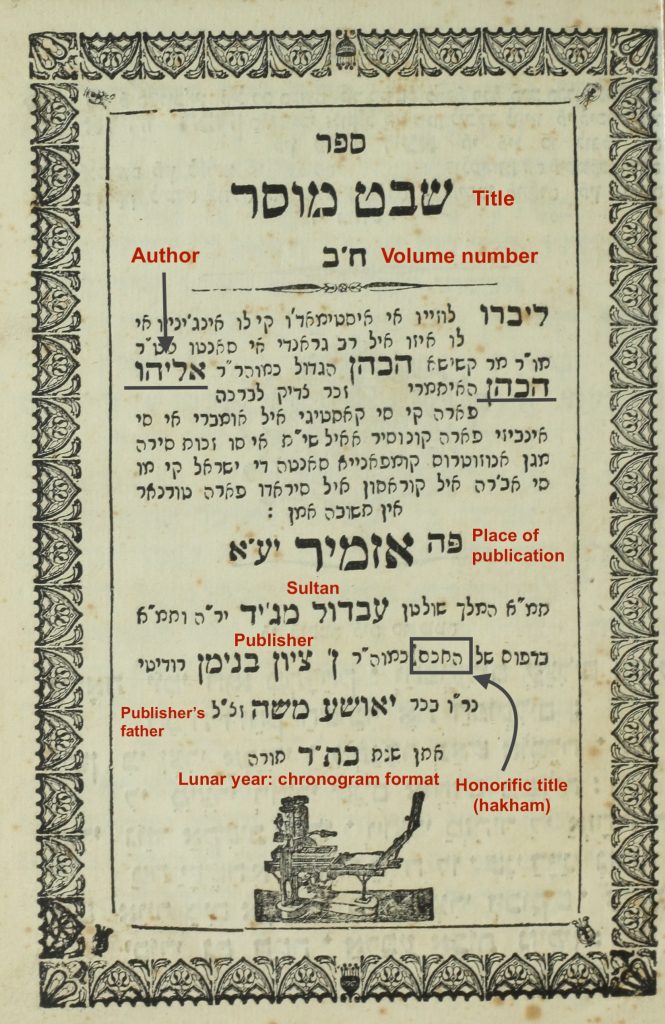

The title page of Olat Shabbat, and the wealth of information it contains, is not unique: Nearly all Ladino books, from translations of the Bible to short novellas to plays, whether published in the 18th or 20th century, often name a multitude of individuals who contributed to the production of a given work. They are sometimes given honorific titles like hakham, a term usually reserved for rabbis and religious leaders. Ladino books were also the site of political negotiations: Names of authors, editors, translators, publishers, and printers — and indeed, often all are mentioned — sometimes appear alongside the name of the reigning sultan at the time, a gesture that helped Jewish printers navigate varying degrees of censorship that the sultan placed on non-Muslim communities through a public, documented expression of gratitude and praise. (Muslims in the Ottoman Empire, and still later in the Turkish Republic, had their own censorship issues to contend with as well, especially with regards to newspapers.)

In short, the title pages of Ladino books show us that their creators viewed book production as an elevated enterprise: as royal as reigning over an entire empire; as sacred as rabbinic service. It was also a collaborative effort. In some cases, the names of all these individuals were printed in the same font size, even in the latter years of Ladino publishing when more typesetting options were available — a visual feature that shows the level of recognition awarded to many of those who participated in Ladino book production.

Annotated title page for the Ladino Shevet Musar (ST00390). At the bottom appears an image of a printing press, perhaps a nod to the fact that printing was uniquely Jewish profession in the Ottoman Empire. (Courtesy Richard Adatto)

The import that Ottoman Jewish book producers placed on their careers was a defining aspect of Ottoman Sephardic culture, but it did not exactly transfer into our current reading context, and by extension, the context in which formal library cataloging standards were developed. Text production has developed to almost exclusively favor the front-facing contributors: writers and editors get the biggest bylines — both in form and in social recognition — while publishers are in the background. Printers are all but forgotten, both by readers and by the dominant English-language library cataloging standards.

The problems with incomplete catalog entries

Clearly, then, shifting social, political, technological, and cultural priorities have impacted the way we have evaluated the importance of bibliographic information for Ladino books, but it has come at a price. “Without proper bibliographies,” one scholar writes, “a historian begins work in a…desert too dry for cultivation.” This comment alludes to two primary problems that emerge when catalog entries for Ladino books do not stay faithful to the bibliographic information provided by the book itself.

Research is hindered

First, an incomplete entry does not serve the goals of a library catalog because it impedes findings when it should facilitate further inquiry. Library catalogs are meant to assist users with three basic activities: finding information; identifying and clarifying relationships between pieces of information; and selecting and obtaining a resource that fulfils their needs. If a student is looking for information on Hayim Nehama (one of the printers of Olat Shabbat described above) and Nehama is not named in the catalog entries for any of the books he printed, how will the student know which primary sources to turn to if their first access point toward these very sources (the library catalog) is not providing adequate information?

Historical figures become invisible

Second, incomplete catalog entries keep understudied historical figures on the margins. Omitting certain Ladino book contributors is striking when the individuals are well-known, but it is especially problematic when they are not.

For instance, in spite of the incomplete catalog entry for Olat Shabbat, Sa’adi a-Levi has been granted significant attention in recent scholarship as a member of what scholars now consider to be the most important Ladino publishing family in Salonica. But it is precisely due to Sa’adi’s historical significance that his omission is so striking: Given his contribution, how could Sa’adi be excluded from a catalog entry?

On the other hand, Sa’adi Ashkenazi a-Levi belongs to a marginalized community seldom the focus of scholarship, including in the field of Jewish Studies; many personalities from the Ladino-speaking Sephardic world have yet to receive even brief scholarly attention. Some of the most prolific Ladino writers, publishing houses, and printers — like Hayim Nehama — remain unknown to many students of Jewish history, Ottoman history, literary studies, and other relevant disciplines. Especially if these figures remain invisible in Jewish studies, scholars working in other related fields may be even less likely to stumble upon them.

Perhaps there are missing links in the biographical sketch of certain historical figures that a catalog entry could begin to fill: a person’s profession, where they lived during a particular time, or even a branch of a family tree. Perhaps the stories of certain individuals remain untold simply because no one knows their names. Until we reach a day when all students and researchers can read Ladino title pages on their own and readily access Ladino books in the first place, the library catalog should more systematically and carefully document the wide array of individuals involved in Ottoman Jewish publishing so that they can finally be acknowledged and studied.

Suggestions for improved catalog entries

Much like the process of creating a Ladino book, rectifying the library catalog will be a collaborative process. Historians, literary scholars, librarians, and others will likely have to work together to determine how to best transfer and represent information from title page to catalog entry. Above all this will require an increased sensitivity to the disparate priorities between the world of Ladino publishing and our current context, which may lead to a reconsideration of certain library standards (the details of which are beyond the scope of this essay).

Many of the cataloging fields (or categories) that may need reconsideration have, in fact, already been debated and studied as a way toward understanding certain genres of Ladino literature. Both Ladino novels and Ladino rabbinic literature (musar), for instance, have been studied in depth by historians, and these investigations have led to important conclusions about the boundaries between original authors and translators (or adaptors, rewriters, and plagiarizers) in the world of Ladino writing. Yet that research has yet to be considered in light of, or as a complement to, the process of library cataloging, where there is a lack of standardization between documenting Ladino authors and translators of works written in other languages into Ladino (among other issues).

A collaborative scholarly effort will open the doors to the world of Ladino publishing, which will in turn rewrite forgotten individuals back into the pages not only of Sephardic history and Jewish history, but also literary history at large.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Thank you for all this information.

I am looking for details on Benyamin Rafael ben Yosef judeo-spanish printing in Constantinople and Jerusalem (end XIXth-early XXth century). Where can I find them ?

Hi Phillipe – this might be a good place to start: https://www.iemj.org/en/onlinecontent/biographies/ben-yosef-benyamin-rafael-1870-1928.html?lang=en

Unfortunately there is very little written about Binyamin ben Yosef, despite how prolific he was as a Ladino printer.