Upon their arrival to the United States, the small population of Sephardic Jews experienced isolation from the much larger American Jewish community. The more than two-million primarily Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews who came to the United States from Eastern Europe initially did not embrace the new arrivals from the Mediterranean region due to their differing language, customs, culture, and geographic origins. These differences led to many struggles as the Sephardim tried to adjust to their new life in the United States without the assistance of already-established Ashkenazi Jews. Because the Ashkenazim sometimes did not even believe them to be Jews, the Sephardim had difficulties finding jobs with Ashkenazi employers and struggled to form their own organizations.

During this time, Sephardic immigrants also distinguished themselves from one another based on their specific place of origin, with each group from Salonica, Rhodes, Monastir, and other towns initially forming its own, small society. Part of the preference to organize separately sprung from the desire, as one commentator noted, to “preserve the dialect, customs, and individuality of the community whence they originally came.” In theory, the intent behind this separation was positive – to preserve the customs of various Sephardic groups – but, the lack of overarching unity was concerning. With the Sephardim already isolated from the rest of the Jewish community, leaders among the Sephardic Jews in New York, including Albert Levy, believed that eliminating internal separation was key to advancing their status and improving their collective lives in the new world.

The year of 1915 marked the creation of the Ermandad Salonikiota de Amerika, or the Salonican Brotherhood of America, a mutual aid society established by Jews from Salonica and one of the most important organizations created by Sephardic Jewish immigrants in New York. Upon his arrival in the United States, Albert Levy became an active member of the Ermandad and worked specifically to break down the barriers between the many city-based groups among the Sephardic Jews and unite them within a single organization. As various eastern Mediterranean groups of Jews came together, united among each other yet isolated from the Ashkenazim, the Salonican Brotherhood of America reestablished itself as the Sephardic Brotherhood of America in 1922. This new name signified the movement toward a broader communal identity among the Sephardim. Albert Levy played an instrumental role in bringing about the name change to the Sephardic Brotherhood by advocating for unity through his writing, through addresses he delivered at Brotherhood meetings, and through activism in the community, more generally.

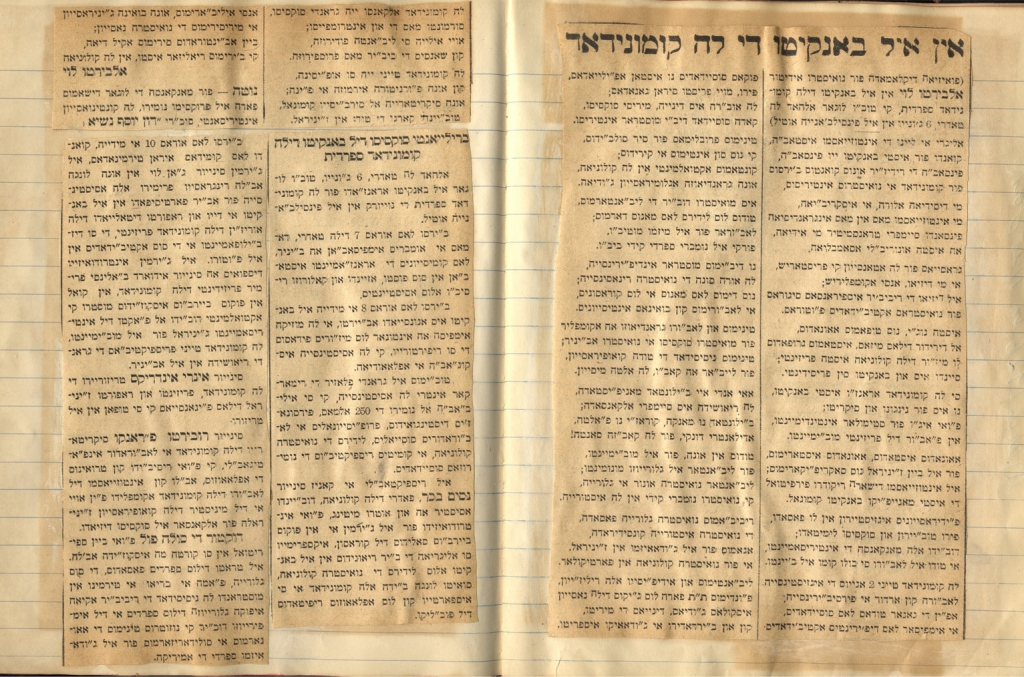

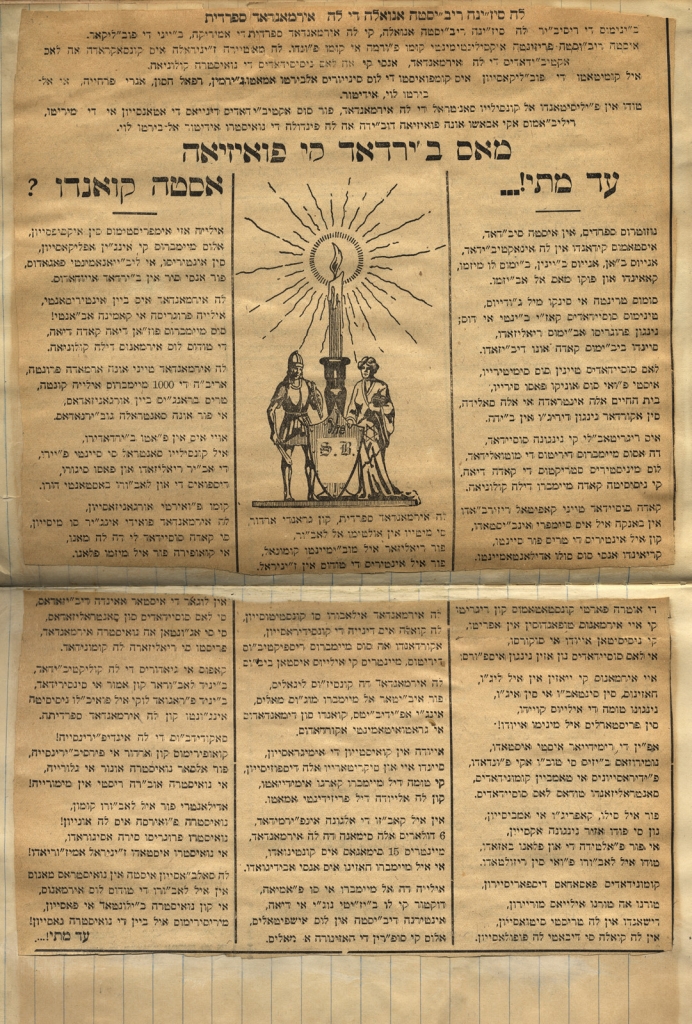

Levy’s immense dedication to the community drove his tremendous involvement in the endeavors of the Sephardic Brotherhood in seeking to unify the Sephardim in New York. Among the clippings in his scrapbooks, Albert Levy included several dealing with his involvement with the Brotherhood: Only two years after its start, Levy had already written of great strides in the community. Read Albert Levy’s poem, “En el banketo de la komunidad.” This work had been preceded by a call to action piece on the same subject. Read Albert Levy’s poem about brotherhood, “Mas verdad ke poezia.” Through writings like these, Levy hoped to foster communal unity.

> TRANSLATED TEXT: “En el banketo de la ermandad”

> TRANSLATED TEXT: “Mas verdad ke poezia. Asta kuando?”

Albert Levy poem: “En el banketo de la ermandad.” Courtesy of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation. (ST00105)

Albert Levy poem: “Mas verdad ke poezia. Asta kuando?” Courtesy of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation. (ST00105)