Julie Philpaut (1780-1834), Racine lisant Athalie devant Madame de Maintenon et Louis XIV (Racine reads ‘Athelie’ for Madame de Maintenon and Louis XIV), Musée du Louvre

By Christina Sztajnkrycer

This piece is a follow-up to “Crossing the Bosphorus: A Sephardic Memoir in a 100-Year-Old French Notebook”, in which Stroum Center contributor Hannah Pressman explored her great-grandmother Estrella Galante’s life as a young woman in Rhodes and Paris, using Estrella’s schooltime notebook as a guide.

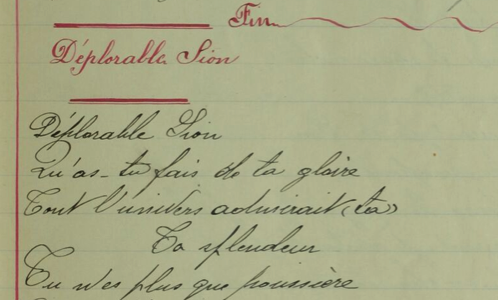

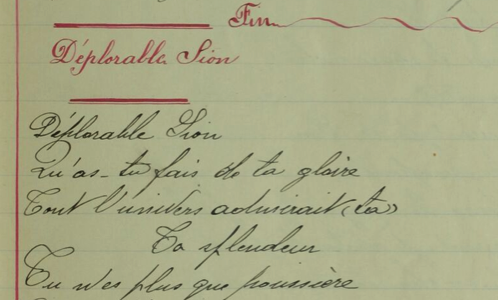

Déplorable Sion

Deplorable Zion

Qu’as-tu fait de ta gloire

What have you done with your glory?

Tout l’univers admirait

All the universe admired

Ta splendeur

Your splendor

(Tu n’es plus que poussière)

You are no longer but dust

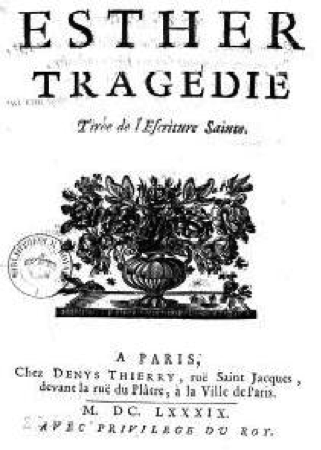

The poem “Deplorable Zion”—written in the notebook that Estrella Galante kept while studying in schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle between 1913 and 1916—comes directly from Jean Racine’s tragedy, Esther. The tragedy Esther was first performed in 1689 at the Maison Royale de Saint-Louis in Saint-Cyr, France. The founder of this institution for girls of poor noble families, Françoise d’Aubigné (known as Madame de Maintenon), was King Louis the Fourteenth’s second and secret wife. Convinced of the pedagogical value of theater, she commissioned Jean Racine, a famous eighteenth-century French playwright, to write a tragedy inspired by the Bible. Racine produced a dramatic retelling of the story of Esther, her cousin Mordecai, King Ahasuerus, and Esther’s role in preventing the king’s advisor, Haman, from convincing him to kill all the Jews of the ancient Persian kingdom. Madame de Maintenon, whose intriguing story of social ascension is unprecedented, was pleased with the moral virtues that the story of Esther would impart to the noble French-Catholic girls of Saint-Cyr.

Here is a summary  of the excerpt from Esther that appears handwritten in Galante’s notebook (a full transcription and translation is available at the end of this essay). In response to Esther’s supplication, an Israelite sings, “Deplorable Zion, what have you done with your glory?” She desires to hear the voices of the young women of the choir mix with her own cries in a celebration and lamentation of the misfortunes of Zion. The sole singer evokes the privileged status of Zion as compared to its contemporary inexistence: the whole universe admired your splendor, you are no longer but dust, and of your grandeur, we are left only with a sad memory. The singer continues to speak of the previous greatness of Zion and its current state of ruin: Zion up the sky once raised, down to hell now fallen. Praising the land, oh! oh! oh! the banks of the Jordan, oh the fields loved by the heavens, sacred mountains, fertile valleys, the singer then asks for how long the exile will last, from the sweet land of our ancestors will we always be exiled, and when Zion will once again attain

of the excerpt from Esther that appears handwritten in Galante’s notebook (a full transcription and translation is available at the end of this essay). In response to Esther’s supplication, an Israelite sings, “Deplorable Zion, what have you done with your glory?” She desires to hear the voices of the young women of the choir mix with her own cries in a celebration and lamentation of the misfortunes of Zion. The sole singer evokes the privileged status of Zion as compared to its contemporary inexistence: the whole universe admired your splendor, you are no longer but dust, and of your grandeur, we are left only with a sad memory. The singer continues to speak of the previous greatness of Zion and its current state of ruin: Zion up the sky once raised, down to hell now fallen. Praising the land, oh! oh! oh! the banks of the Jordan, oh the fields loved by the heavens, sacred mountains, fertile valleys, the singer then asks for how long the exile will last, from the sweet land of our ancestors will we always be exiled, and when Zion will once again attain greatness, when will I see, oh Zion, the ramparts being risen with the magnificent spires of your towers? Completing the song with a final question, the young Israelite asks when the people of Zion will come from all over to partake in the party, when will I see from all over your people in song rush to your parties?

greatness, when will I see, oh Zion, the ramparts being risen with the magnificent spires of your towers? Completing the song with a final question, the young Israelite asks when the people of Zion will come from all over to partake in the party, when will I see from all over your people in song rush to your parties?

The same twenty-four lines from Racine’s Esther appear twice in Estrella Galante’s notebook. Could it be a pure coincidence that she copied these lines from Racine’s biblical and Jewish-themed tragedy at two different times and possibly in two different places, first at her Alliance school on Rhodes and then at her teachers’ training academy in Paris? Coincidence is a possibility, but there seem to be too many significant indicators pointing to the intentionality behind the two-fold appearance of the same twenty-four lines that Estrella included in her notebook to be purely coincidental. The original pedagogical purpose of Racine’s Esther, the fact that Madame de Maintenon commissioned this tragedy for a girls’ school, and the particularly Jewish attributes of the tragedy, all suggest that the duplication of these lines was intentional. The origin of the intentionality, however, lies in the raison d’être of the Alliance Israélite Universelle.

Created by a group of six young and enthusiastic French Jews in 1860, the Alliance Israélite Universelle was inspired by the universal motto of the 1789 French Revolution, liberté, égalité, fraternité. The founding members of this group desired to bring the advantages of the French Revolution, such as religious freedom and Jewish emancipation, to oppressed Jewish communities everywhere. Their venture was greatly motivated by the “civilizing mission” of the French colonial exploits. While the general French objective in the Maghreb—Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco—involved, but was not limited to, what France loftily saw as bringing enlightened French culture to backward, uncivilized peoples, the founders of the Alliance Israélite Universelle adopted a similar ambition for the Jewish communities throughout the Muslim-dominated world. They believed that through French culture, the Jews of the Levant and northern Africa could free themselves of oppression and enjoy the liberties that French Jews had enjoyed in France since the 1791 decision of the Assemblée Nationale to grant them citizenship and full and equal rights in France.

Eugène Delacroix, Mariée juive à Tanger (Jewish Bride in Tangier)- Rachel Azencot-Benchimol, 1832

Implementation of the French “civilizing mission” that the Alliance had adapted to a Jewish purpose occurred across the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East through the creation of schools in which French language, art, culture, literature, and history were the basis of the entire curriculum. One particularity of the Alliance mission was the opening of schools for both boys and girls in places where female education was almost unimaginable. The intent was that the young women educated in the Alliance schools would introduce the ideals of the Alliance to the family setting, educating in turn their children with the enlightened ideas of French culture. Estrella Galante was one of the fortunate young women to benefit from the education offered to Jewish girls through the schools of the Alliance. As an exemplary student in her Alliance school on Rhodes, Estrella was also chosen to participate in the École Normale Supérieure Orientale in Paris in order to become herself a teacher in the Alliance schools. Estrella’s time in Paris prepared her for a brief teaching career that she undertook on Rhodes before setting off for marriage in southern Africa.

With pages full of French songs, poems, dialogues, and folk culture, Estrella Galante’s notebook is tangible evidence of the use of French language, art, culture, and literature in the Alliance curriculum. While there are many popular songs contemporary to Estrella’s time penned in her school notebook (that appear to contradict the Alliance’s objective of enlightenment), there are also serious pieces like the lines from Racine’s tragedy that reinforce the importance of intellectual French culture that was emphasized in Alliance schools. The choice of Racine’s tragedy Esther, originally written for a purely French-Catholic and specifically young female public, takes on a particular pertinence to the project of the Alliance, serving as a bridge between French intellectual culture and Jewish history.

The French consider the plays of Jean Racine to be classics of French literary and theatrical culture. His tragedies in particular are seen as ideal representations of the classicism movement in Europe between the middle of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century, prior to the Enlightenment. The cultural importance of Racine’s works is demonstrated by the frequency with which Marcel Proust, the iconic French-Jewish writer of the early 20th century, mentions Racine. In the volume entitled In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the narrator obsesses over Racine’s Phèdre and the baron de Charlus, one of Proust’s infamous characters, proclaims: “There is more truth in a single tragedy of Racine than in all the dramatic works of Monsieur Victor Hugo” (quoted in Antoine Compagnon, “Proust on Racine”, 23).

Théodore Chasseriau, Esther se parant pour être présentée au roi Assuérus (Esther prepares to meet King Ahasuerus), 1841

Although it is not Racine’s Esther that caught the attention of Proust’s narrator, the idea and image of this biblical female character was popular in French culture. Esther is the heroine of Honoré de Balzac’s novel Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans, published between 1838 and 1847. Théodore Chasseriau painted Esther in 1841 as she prepared to present herself to King Ahasuerus in the biblical tale. According to Eric Fournier, author of La “Belle juive”: d’Ivanhoé à la Shoah, the beautiful Jewess was something of a cultural phenomenon in 19th-century France. The imagery surrounding the Jewish female began in France with the translation of Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe in 1819 and increased with the French colonial endeavors in North Africa, where artists like Eugène Delacroix traveled to paint Jewish women for Orientalist paintings. Back in France, Jewish women benefitted from the mystery associated with the beautiful Jewess and garnered great artistic and social success. Rachel Félix became one of France’s most famous opera singers while Thérèse Lachmann, known as La Païva, and Sarah Berhardt’s mother, Judith-Julie Barnardt, called Youle, became famous courtesans, and Joséphine Marix became an eminent Jewish artist’s model. Esther, as a Jewish heroine, embodied the allure and accomplishment of Jewish women and was culturally important in both the French artistic imagination and the Jewish canon.

For Estrella Galante, the few lines picked from the Jewish-themed tragedy of Jean Racine initiated her to a unique cultural experience: not only studying Racine, but also studying the curious figure of the Jewish female in French culture from the perspective of a Jewish female. As a young girl, Estrella had the opportunity to experience French culture through her studies at the Alliance Israélite Universelle on Rhodes. At the École Normale Supérieure Orientale in Paris, she prepared herself in turn to assume the role of a teacher of French culture, tasked with continuing the mission of the Alliance to bring enlightened French culture to Jewish communities internationally. Like Esther, Estrella must have believed in the importance of protecting Jewish communities, and she did so through her adherence to the ideals of the Alliance Israélite Universelle.

Déplorable Sion

Qu’as-tu fait de ta gloire

Tout l’univers admirait

Ta splendeur

(Tu n’es plus que poussière)

Et de cette grandeur

Il ne nous reste plus

Que la triste mémoire

Sion jusqu’au ciel

Elevé autrefois

Jusqu’aux enfers

Maintenant abaissé

(Puissé-je demeurer sans voix

Si dans mes chants ta douleur retracée

Jusqu’au dernier soupir n’occupe ma pensée!)

Oh ! oh ! oh ! rives du Jourdain

Ô champs aimés des cieux

Sacrés monts fertiles vallées

Par cent miracles signalées

Du doux pays de nos aïeux

Serons-nous toujours exilés

Quand verrai-je ô Sion

Relever tes remparts

Et de tes tours les magnifiques faîtes

Quand verrai-je de toutes parts

Tes peuples en chantant

Accourir à tes fêtes

Deplorable Zion

What have you done with your glory

All the universe admired

Your splendor

You are no longer but dust

And of your grandeur

We are left only

With a sad memory

Zion up to the sky

Once risen

Down to hell

Now fallen

(Could I remain voiceless

If in my songs your pain retraced

Until my last breath occupied my thoughts!)

Oh! oh! oh! the banks of the Jordan

Oh fields loved by the heavens

Sacred mountains, fertile valleys

By one thousand miracles signaled

From the sweet land of our ancestors

Will we always be exiled

When will I see, oh Zion,

The ramparts being risen

With the magnificent spires of your towers

When will I see from all over

Your people in song

Rushing to your parties

*Translated from Estrella Galante’s notebook by Christina Sztajnkrycer

Christina Sztajnkrycer (Sutton) received a research grant from the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies for her translation work on the Estrella Galante notebook. A former Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar, Christina received her Ph.D in French from the University of Washington in December 2016. While she finds all forms and periods of literature intriguing, Christina is particularly interested in 19th- and early 20th-century novels depicting Jewish characters in an evolving French society.

Christina Sztajnkrycer (Sutton) received a research grant from the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies for her translation work on the Estrella Galante notebook. A former Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar, Christina received her Ph.D in French from the University of Washington in December 2016. While she finds all forms and periods of literature intriguing, Christina is particularly interested in 19th- and early 20th-century novels depicting Jewish characters in an evolving French society.

Links for Further Exploration

- Learn more about Estrella and her notebook, and see more of Christina’s translation work, in “Crossing the Bosphorus: A Sephardic Memoir in a 100-Year-Old French Notebook” by Hannah Pressman (Dec. 2016)

- “An Ottoman Jew in Paris” by Christina Sztajnkrycer (May 2015)

- “How Are Jews Depicted in French Literature? by Christina Sztajnkrycer (Jan. 2015)