Documents from the Pepo Allalouf archive, digitized by the Sephardic Studies Program. All documents courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw.

By Dimitris Mitsopolous

Six years ago, after graduating from high school, I was admitted to the Department of History and Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece. My childhood dream to become a historian had been fulfilled. I had planned to study the history of Greece’s European integration and the historical origins of the Greek economic crisis. But two events led to a major shift in my focus.

For my birthday, during the first year of my studies, I received an important work of history as a gift: Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews written by Columbia University professor Mark Mazower, which enabled me to delve into the history of my hometown, Thessaloniki — or Salonica, as it was often known by the city’s Jewish community. The book opened me to the city’s multicultural past, and Salonica’s complex relationship with the past and present. I discovered for the first time the city’s colorful past, and the fact that its very makeup was totally different a century ago.

During my studies, I also met several professors who sparked my interest in Salonica’s Sephardic past. Most of them were specialists in Jewish history or the history of the Ottoman Balkan region, and they showed me how interconnected these two histories are.

Most people in Greece are surprised when they hear that I am interested in the Jewish history of Salonica. Many have asked me if I myself am Jewish. For some people, it’s difficult to understand how a non-Jew could be interested in Jewish history; but the way I see it, Thessaloniki’s Sephardic past is not an exclusively Jewish matter, but rather one of the most — if not the most important — aspect of the city’s history.

My interest in better understanding the history and culture of my city led me to Professor David Bunis’ Ladino Language and Culture course this summer at the University of Washington (UW), in which I was able to participate thanks to the generous support from Sephardic Studies Program at the UW. In summer Ladino I benefited greatly from Professor Bunis, who is an excellent instructor, but also from the vivid discussions amongst the students that enabled me to gain new insight into the historic language and culture of Salonica’s Jews.

Moreover, I had the chance to “meet” and explore the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection (SSDC), the University of Washington’s digitized collection of Sephardic texts and archival materials, which is a real treasure for the field of Sephardic studies. Within the SSDC I encountered the story of Salonican-born Pepo Allalouf, whose life and journey follows the major historic developments impacting the city’s Jews and intersects with contemporary Greek and American histories, too.

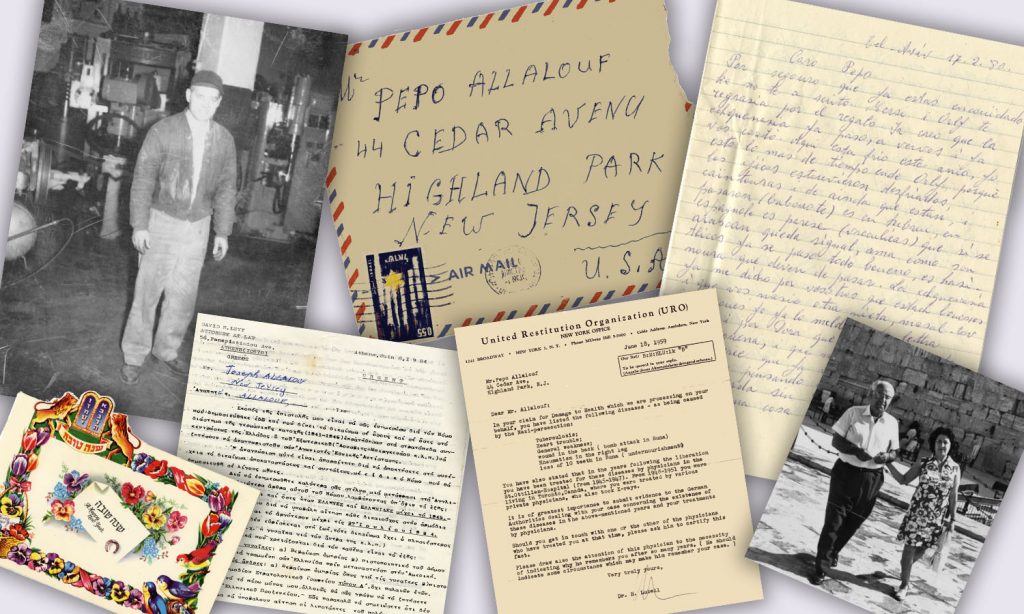

Undated photo of a young Pepo Allalouf (ST02027-285, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw).

The Allalouf archive contains 250 documents and photos spanning from 1945 through the mid 1980s. It consists of letters between family members in the United States or Israel, correspondence with legal services in Greece, documents about the liberation of the concentration camps, and Pepo’s situation and claims for reparations for his sufferings during the Holocaust.

Pepo Allalouf’s life includes some of the most characteristic elements of the life of a Salonican Jew born in the early 1910s: In Pepo’s letters and documents, now digitized by the Sephardic Studies Program, we can trace major historical events as they were lived by one individual. These milestones in the city’s history include Salonica’s passage from the Ottoman Empire to the Greek nation-state; the infamous fire that ravaged the city in 1917; interwar immigration; military service during the Greek-Italian War in 1940-41; the Holocaust; survival; and immigration.

A fire forces a Jewish Salonica to rebuild

Born in 1910 in Ottoman Salonica, Pepo belonged to a generation of Salonican Jews born in a city which, only a couple of years later, in 1912, would become part of the Greek nation-state. In 1917 the city was partly destroyed by a fire, which significantly impacted the Jewish neighborhoods in Salonica, while a dramatic downward social mobility followed for most of the Jews: the vast majority — especially poor Jews — lived in the city center, which was squarely within the area destroyed by the fire.

Postcard showing the aftermath of the 1917 fire in Salonica. (Source: Beth Hatefutsoth Photo Archive, Salonika Collection, photo unit number: 1489.)

The destruction left 70,000 people homeless, and of them, 52,000 were Jews. Pepo was one of the displaced, so he and his family moved in with one of his uncles. Pepo then enrolled in a Greek school like many of his peers who did not come from the upper social class. Beginning in the late 1910s, some of his family members started leaving Greece for the United States.

Military service: Greek pride, as a Jew

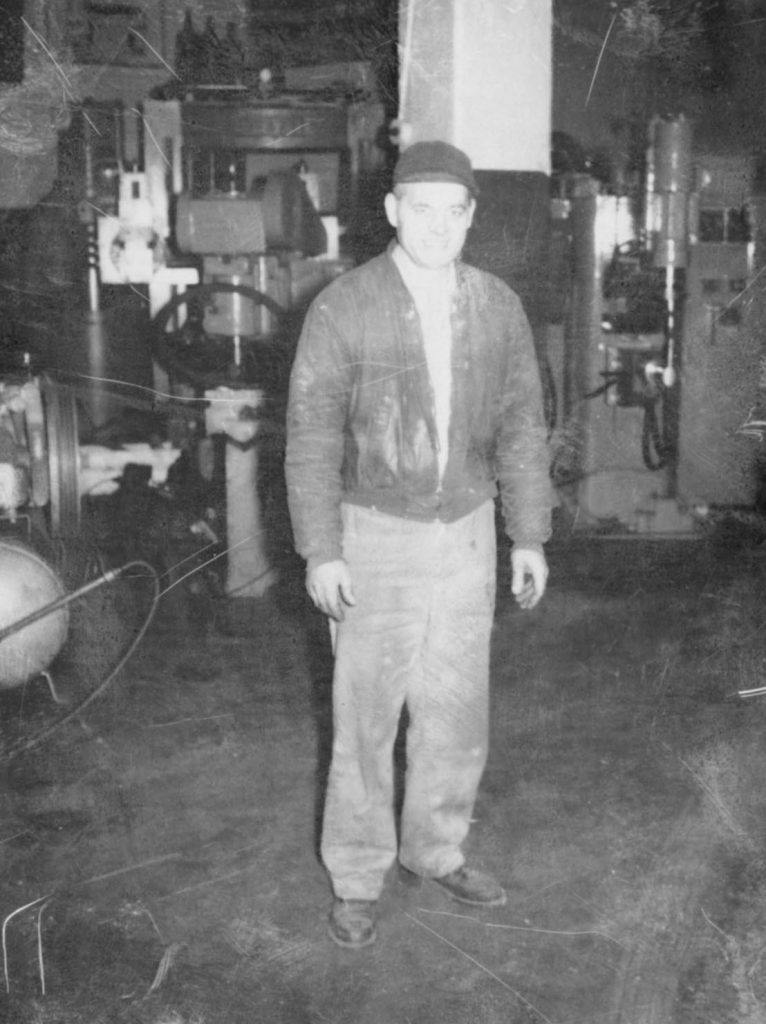

Biographical note accompanying the Allalouf papers describing Pepo’s movements during the 1930s. (ST02027-052, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw.)

Pepo and his father also left Salonica, but instead of going to the United States like most of their family, they left for Mandatory Palestine, which, at the time, was controlled by the British. Nevertheless, a few years later, Pepo returned to Salonica, where he opened a baby carriage shop (unfortunately, none of Pepo’s preserved documents explicitly state the shop’s address).

The turbulence of WWII brought Pepo to the Greek army where he was drafted to fight against the Italian invasion. Although I was not able to locate a direct testimony from Pepo about his experience in the Greek army, the narrations of other Salonican Jews during the Greek-Italian war express a shared experience of pride for their service without any barriers or cleavages of religion, for the majority of them (the so-called Koen Brigade, for example, was comprised only of Jews because of the Greek military administrative practice of establishing units based on place of residence; the participants in this brigade all came from the same neighborhood in Salonica). As another Salonican Jew, Sam Askanazi, put it, “We, the Greeks, we were fighting very hard”, while Samuel Castro characterized the war in an oral history as “a very nice experience.”

Nazi occupation: A community destroyed

According to a biographical note prepared by Pepo’s descendants, a few months after the Nazis invaded Salonica, Pepo tried to escape and flee Greece through the Aegean Sea, but his attempt was unsuccessful. The conditions of Nazi occupation were becoming harder and harder: Beginning in July 1942, the anti-Jewish measures in Salonica began to escalate as the Nazi occupation forces conscripted Jewish men for forced labor, while in December of that year the Jewish cemetery was destroyed and vandalized by local collaborationist authorities.

As Devin Naar describes in his book, Jewish Salonica (2016), the request by local Greek Christian authorities for the removal of the Jewish cemetery from the city center had been a controversial issue during the interwar period and a main obstacle in the relations between the Jewish community and the Greek state and local authorities. Although Pepo does not mention this major historical event in his letters, it is important to mention in order to understand the tenor of Greek-Jewish relationships in Salonica at the time.

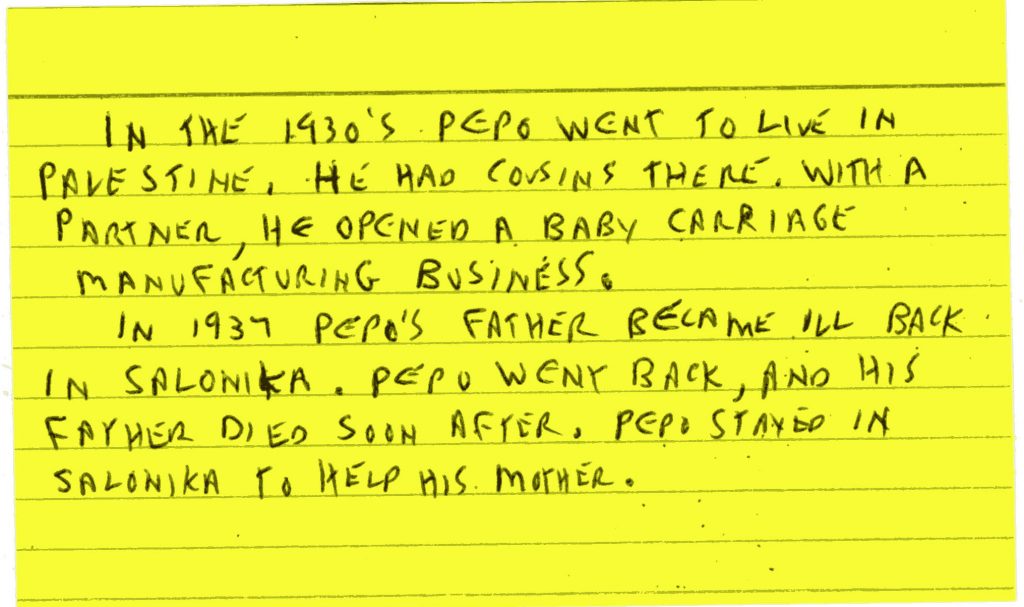

Postcard overlooking the Jewish cemetery in Salonica (1910s). Source: WikiCommons.

After the Nazis invaded Greece and started implementing anti-Jewish measures, the local collaborationist authorities pressed the German authorities to enable them to “remove” the cemetery. Finally, in December 1942, the local cemetery, one of the largest and most important Jewish burial sites in Europe, was totally destroyed and desecrated, while the stones were used as a building material. Some of them remain visible today.

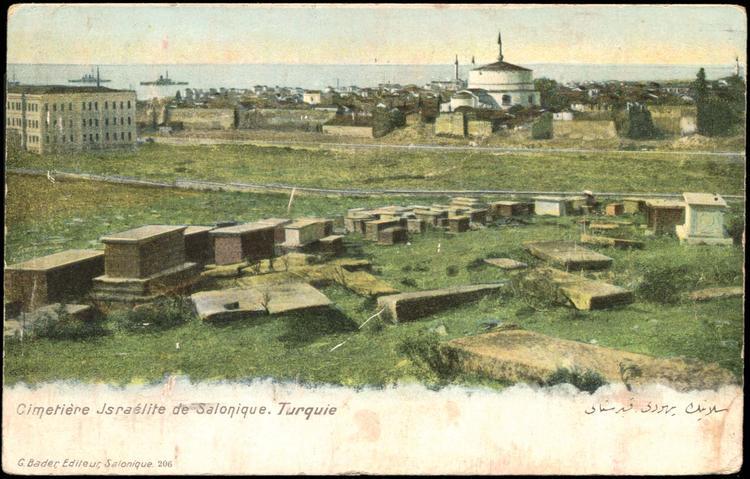

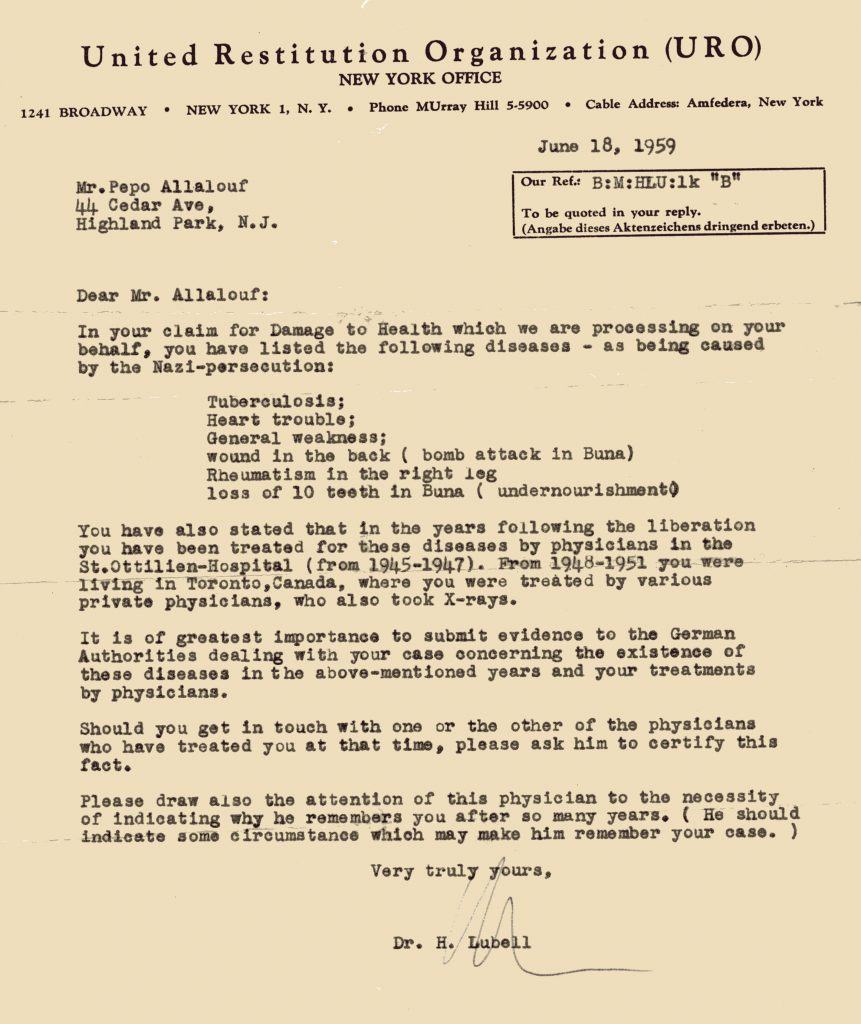

Restitution documentation for Pepo Allalouf recording his ailments upon liberation by the Red Army (ST02027-014, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw).

In February of 1943, ghettoization forced Salonica’s Jews from their homes and into a designated neighborhood, while a month later the first train to Auschwitz departed from Salonica.

Pepo’s family was deported in early April, and he was the only one to survive from his family. In one of his later letters, attempting to claim his family inheritance, Pepo readily identifies himself as a survivor: “My name is Pepo Allalouf,” he writes, “and I lived in Thessaloniki until March 1943. Then the Germans transported me to the concentration camp, along with my brother and my family. With difficulty, I have remained alive.”

Pepo’s skills and working experience were crucial for his survival, although the conditions had been extremely harsh. When Nazis started to evacuate the camps as the Soviet Army approached, Pepo took part in the Death Marches from one camp to another. As the document at right shows, the liberation by the Red Army found Pepo sick, with multiple diseases.

Survival, immigration, and memories of Salonica

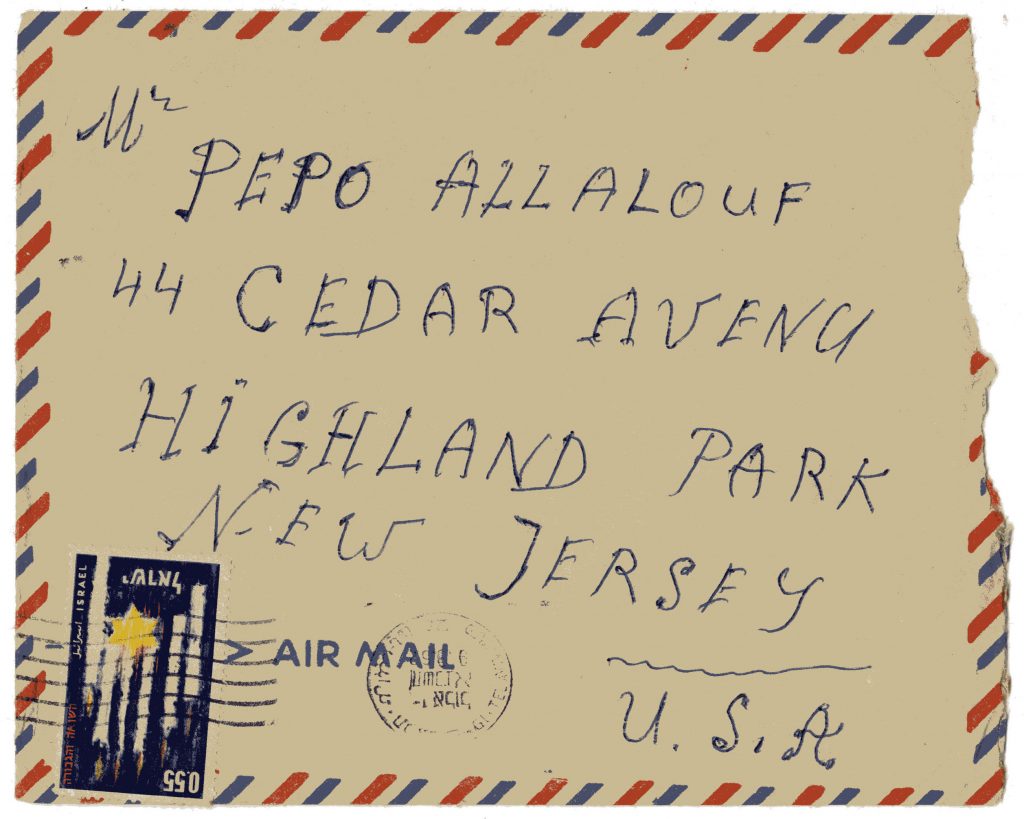

One of many letters addressed to Pepo from Israel to his New Jersey address. From the early twentieth century through today, Highland Park is home to a Sephardic synagogue founded by Jews from Salonica. (ST027-028, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw.)

Pepo, like many other survivors, wanted to move to the United States after the liberation. Besides his personal sufferings, the Jewish community of Salonica was totally destroyed; most of its survivors would either leave for Palestine or the United States.

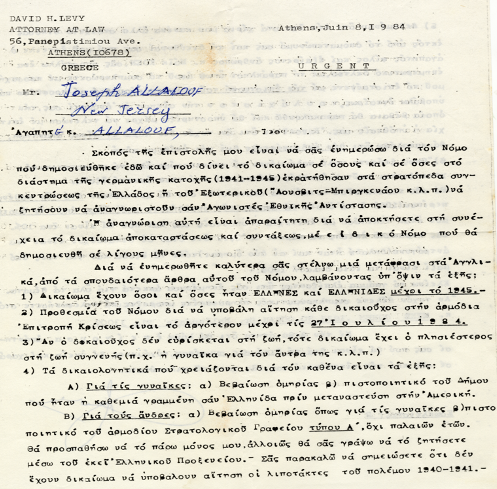

1984 correspondence between Pepo and an Athens attorney documenting Pepo’s application for pension from the Greek state (ST02027-271, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw).

In one of Pepo’s Greek letters from 1966, narrating his family’s history and his struggle to regain the family’s property, we read not only of the tragic fate of his family (including his sister and mother), but also of the diseases Pepo suffered after the liberation. In his own words, Pepo expresses that his lungs were “destroyed” and he was unable to do many things as a consequence.

Finally, there is the matter of his family business: In a letter (likely to a director of a Greek public service), Pepo makes the painful claim as the sole survivor in his family: “My sister was assassinated in the concentration camps by Germans,” he writes. Now Pepo aims to reclaim the site of his family business (a different store than his aforementioned baby carriage shop), “a shop at Tsimiski 10” — a store location that would have been in the center of downtown Salonica.

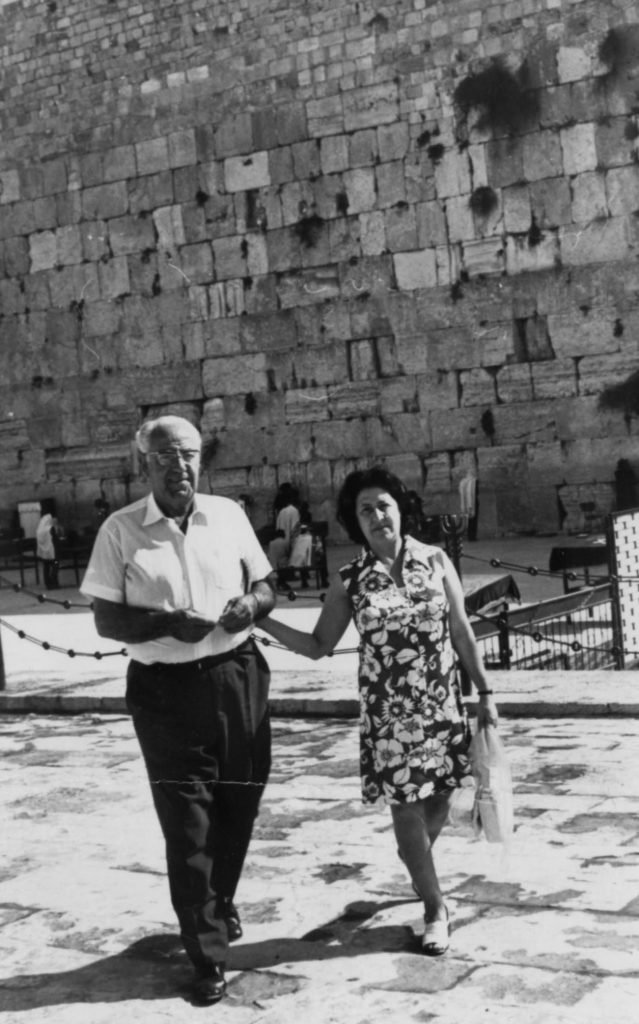

Although Pepo declared his interest to move to the United States, he was unable to do so. His first post-war home was in Toronto, where he worked for a couple of years. Finally Pepo was able to move to New Jersey, where he lived for the rest of his life with his wife, Dora.

Despite the long distance, Pepo kept in touch with family members and some other Salonican Jews, some of whom had also left Salonica but had settled in other places, like Los Angeles. The letters show not only their willingness to stay connected, but also the close bonds between members of the once thriving Salonican Jewish community, even if these bonds stretched in two or three continents. They were discussing their personal lives, their past and providing assistance one to another, when someone was in need.

Pepo and his wife, Dora (née Mair) traveling in Israel (ST02027-153, courtesy Benita Allalouf Brokaw).

Another dimension to the correspondence, which should not be omitted, is of these survivor’s attempts to find justice for what they suffered during the Holocaust. Pepo applied for reparations (Wiedergutmachung), as a victim of the Nazi persecution because he suffered from multiple diseases. In the mid-1980s he was able to apply for an honorary pension from the Greek state. (I was not able to trace the fate of his application, but it was likely accepted.)

Pepo Allalouf’s life was usual and unusual at the same time. His life often parallels the experiences of his peers from Salonica born in the early twentieth century. On the other hand, how many people have lived through so many dramatic changes, like the passage of their city from an empire to a nation state, the destruction of their home from a fire, immigration, war and, most of all, the ineffable tragedy of the Holocaust? In the broader context of history, these details of Pepo’s life certainly render his experiences unique, and his survival a triumph.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Dimitris Mitsopoulos is an MA student in Global History at the Free University and Humboldt University of Berlin. He majored in history during his undergraduate studies at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Dimitris is mainly interested in Sephardic history and Greece’s passage from the Ottoman Empire to a nation-state. He was a student in the UW’s summer 2020 Ladino Language and Culture with Professor David Bunis.

Dimitris Mitsopoulos is an MA student in Global History at the Free University and Humboldt University of Berlin. He majored in history during his undergraduate studies at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Dimitris is mainly interested in Sephardic history and Greece’s passage from the Ottoman Empire to a nation-state. He was a student in the UW’s summer 2020 Ladino Language and Culture with Professor David Bunis.