By Makena Mezistrano

As its former inhabitants will tell you, my own grandparents included, there is no place like Thessaloniki — though my grandparents never called it that. For them, and for much of the once 60,000 strong Jewish community, the city was called by its Ladino name: Saloniko. Some called the city by one of its many other names, each reflective of the ever-shifting demographics and politics: sometimes in Hebrew (Saloniki) or Turkish (Selanik), later in French (Salonique), and finally, in Greek (Thessaloniki). Depending on the place, the conversation, and the moment, one may have used each name in a single day.

Salonica’s other monikers have also transformed with the city: Ladino newspapers before World War II called it madre de Yisrael (mother of Israel); my grandfather called it “the jewel of the Mediterranean.” Later in life, as she recalled returning to an unrecognizable Salonica after hiding in Athens during the Holocaust, my grandmother borrowed a different nickname: “city of ghosts.”

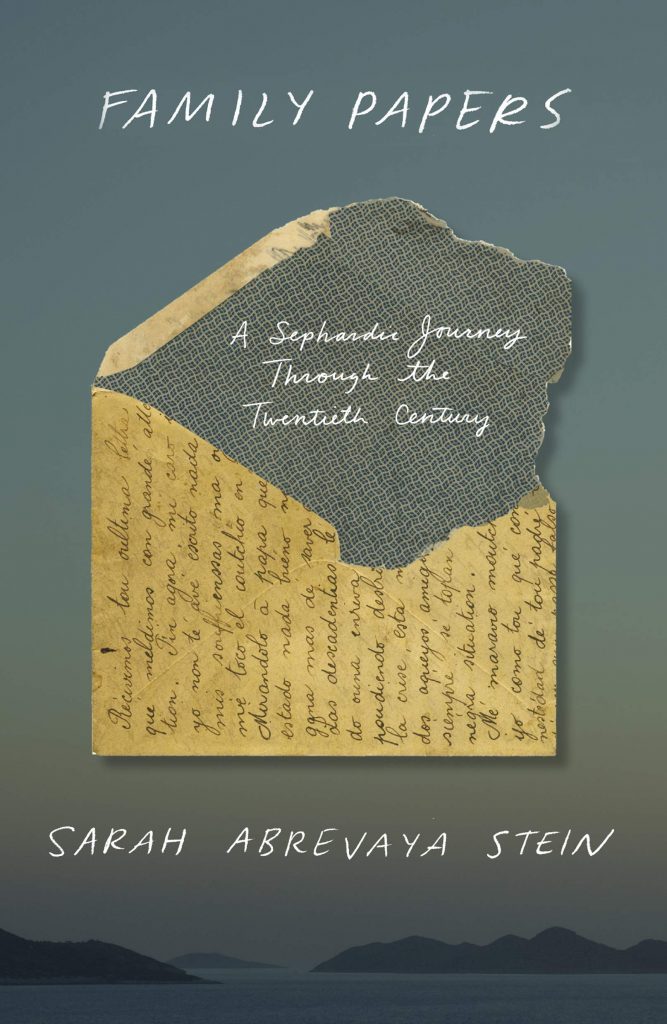

As Salonica’s name changed, so did the people who lived there. The shifting aspirations and fates of the city’s Jews is the topic of Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century by Dr. Sarah Abrevaya Stein, chair of Sephardic Studies and director of the Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies at UCLA. Her new book is the story of the a-Levi family, the Lévy family, and the Levy family. They really are all one clan, but as Salonica transformed both in name and in its very fabric, so did the Levy name.

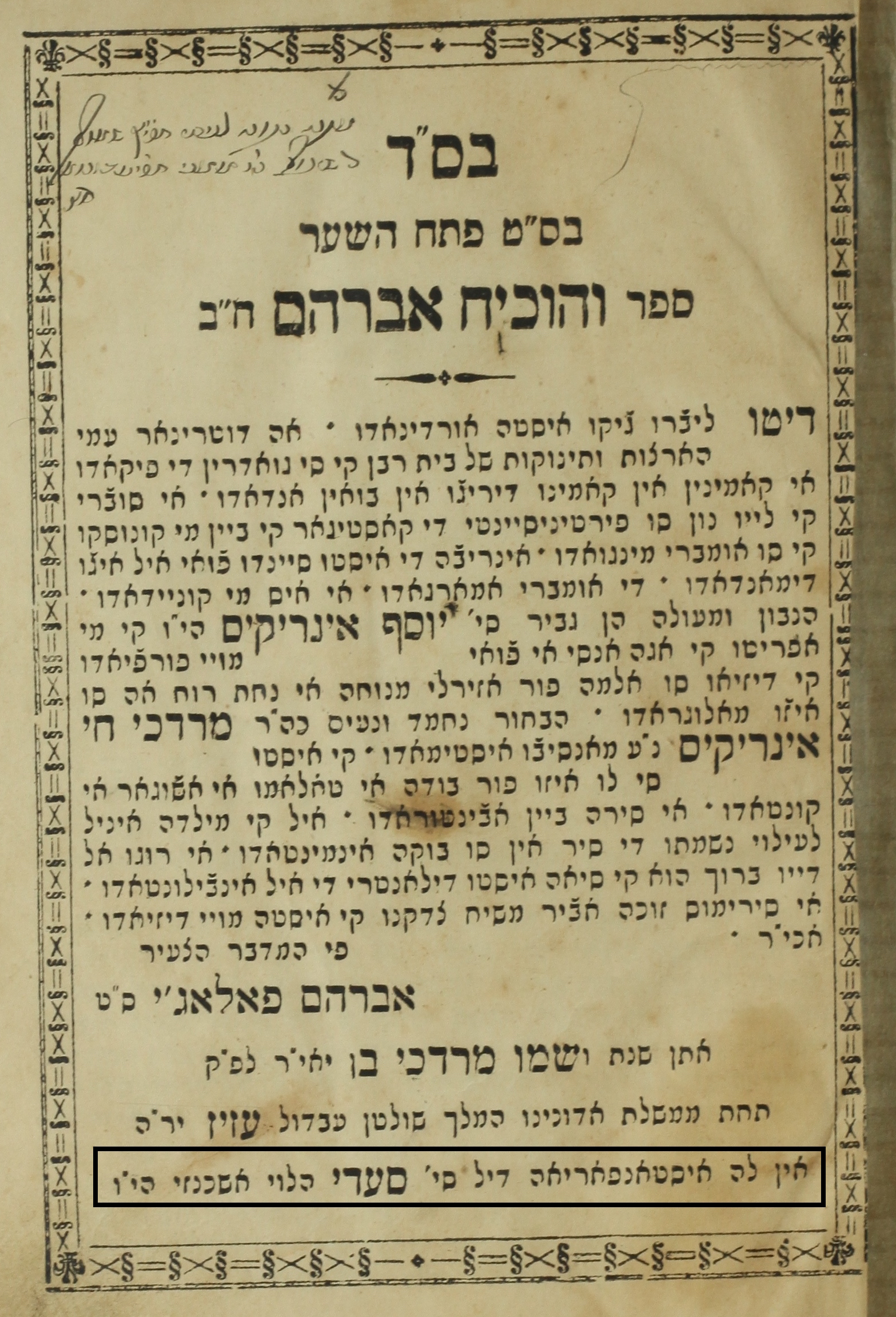

Stein’s book is over a decade in the making. After completing her translation (with Aron Rodrigue and the late Isaac Jerusalmi) of the memoir of Sa’adi Besalel Ashkenazi a-Levi, the Levy family patriarch and local rabble-rouser (as Stein describes), Stein stayed in contact with Sa’adi’s descendants scattered across Montreal, Rio, Johannesburg and elsewhere. Eventually, she collected a cache of letters preserved from the late 19th century to the 1970s. The correspondence forms the basis for Family Papers with important additions from archives in Salonica, Paris, and Jerusalem; French and Ladino newspapers (with many articles penned in Salonica and Paris by the journalistic Levys themselves); Holocaust survivor testimonies; and conversations with the family over the years.

Stein’s book is over a decade in the making. After completing her translation (with Aron Rodrigue and the late Isaac Jerusalmi) of the memoir of Sa’adi Besalel Ashkenazi a-Levi, the Levy family patriarch and local rabble-rouser (as Stein describes), Stein stayed in contact with Sa’adi’s descendants scattered across Montreal, Rio, Johannesburg and elsewhere. Eventually, she collected a cache of letters preserved from the late 19th century to the 1970s. The correspondence forms the basis for Family Papers with important additions from archives in Salonica, Paris, and Jerusalem; French and Ladino newspapers (with many articles penned in Salonica and Paris by the journalistic Levys themselves); Holocaust survivor testimonies; and conversations with the family over the years.

The volume of archival documentation Stein consolidated is massive and forms what is, for the most part, an intricately detailed portrait of the Levys and their world. But Stein reminds us time and again that her research is tethered to a most fragile source: family papers. Literally, Stein describes some of the documents she handled as thin as onion skin. Figuratively, circumstances render some elements of the story uncertain.

Some paths of the Levy clan are undocumented. Some members met the fate of most of Salonica’s Jews and were exterminated at Auschwitz without a trace of any material legacy. Piecing together the chronicles of a family that lived through transnational migration, political transitions, and genocide leaves certain details shaky.

At several points in the narrative, we are forced to move from an elaborate portrait of one Levy to a faded sketch of another. One of the many sections about Daout Effendi — one of Sa’adi’s sons who became a high ranking Ottoman official and an important functionary for the Salonican Jewish community — is followed by a chapter with a caveat from Stein. In this chapter we meet Fortunée, one of Sa’adi’s daughters, and Stein admits that no papers in Fortunée’s hand have survived. Although Fortunée is memorialized in photographs, which are important archival documents in their own right, Stein considers all that a photo does not tell: after all, how much can we glean about an individual from posed portraits?

Ladino title page of Sefer ve-hokhiah Avraham, published in Salonica by Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi, 1852. (Courtesy of Al Maimon, ST00754)

In the absence of her own words, Fortunée’s story becomes less about her and more about what her generation represented for Salonican Jewry: Desiring upward social mobility, their age saw the first major move out of the Jewish neighborhoods to the seaside suburb of Las Kampanyas — where my grandmother’s family lived — and more children began to move in non-Jewish circles when they enrolled in Greek Christian schools.

It is surely painful to be unable to treat all subjects of Family Papers evenly, but one of the challenges that Stein faces head on is to tell the story of one family member, Vital Hasson — a Nazi collaborator — that the Levys themselves did not want to be told. Though Hasson was effectively excommunicated from his family and also not mentioned in their papers, his imprint remained in survivor testimonies and, for Stein, is impossible to ignore at risk of “sanitizing” the truth. Nonetheless, she admits some discomfort at seeing a photo of Sa’adi (who never knew what his progeny could become) in the Montreal home of Vital’s daughter.

Though Stein does not address how her own identity may have also played a role in this uncomfortable moment, I do wonder about what it means to be a Sephardic historian who studies Sephardic history. Because as I read Family Papers, I could not help but do what I always do: I read Sephardic history as a Sephardic person, and — even when I did not want to — I saw shades of my own family’s story in Stein’s casting of the Levys.

Saltiel family wedding in Salonica, 1933. Author’s great-grandparents, Flora and Albert Saltiel, immediately left of framed photograph. Courtesy Lela Abravanel.

Stein describes many of the Levy women as saviors rescuing the family from poverty with their craft, and commanding authority in their households — an unexpected role for their milieu. My own great-grandmother — against the behest of all her extended relatives — saved her immediate family when she marched them out of the ghetto each night just before the trains departed for Auschwitz; hid with a Greek Christian neighbor; and, in a final act of resistance, shredded their yellow stars.

For all readers, Family Papers demands we see the other side of a historian’s work where silence is the close companion of discovery. If we were to embark on decoding our own family papers, what might we find? And when the papers do not yield what we hoped for, or they are not there at all, can we — should we — fill the silence?

National acclaim for Family Papers

- An intimate chronicle of Sephardic Jewish history | The Economist

- Meet the Levy family. Their history is our history. | The New York Times

- Melancholy Recollections: On Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s ‘Family Papers’ | LA Review of Books

- ‘Family Papers’ Review: Diaspora and Destiny | The Wall Street Journal

Leave A Comment