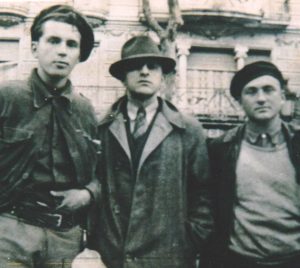

Abe Osheroff, Soldier, 1915-2008

- What was it like to be a Communist as a Jew?

- What motivated you to join the war?

- How much did Hitler factor into the decision to join the war?

Abe Osheroff, 22, in 1937

Abe Osheroff lived in Seattle for the last 20 years of his life. He was a moving force behind this project; indeed, anyone who knew Abe would agree that he was a moving force.

A carpenter by trade, he joined the Young Communist League at age of 16. Soon he was well-known on the streets of his native Brownsville, Brooklyn, as a public speaker and an activist organizing demonstrations and resisting evictions in the neighborhood—all of which may account for his resistance, within the Party, to the practice of Anglicizing Jewish names. If a Jew was evicted for non-payment of rent in Brownsville, the landlord was also a Jew.

The cop who came to break up the demonstration was also Jewish, and Abe says (minus expletives) “the Jewish cops hit just as hard, beat you just as bad.” Presumably, there would have been no benefit to changing his own name. For Abe Osheroff, class conflict transcended but did not diminish his Jewish identity: “It transcended the Jewish question. The class question became more important.”

What was it like to be a Communist as a Jew?

The insistence by the Party that some of its most active members Anglicize their names points to what Abe saw as its ambivalence around what they always called “the Jewish Question.”

Abe did begin organizing in coal and steel, and was pleased to show people in those industries what a Jew could do, though sometimes that took a little arm-wrestling or a punch or two. The same was true later, in the U. S. Army, where soldiers asked him what a Jew was doing in the infantry. Shouldn’t he be in the Quartermaster Corps…or in the band? In Spain, where most of his comrades were Jewish, no explanation was necessary.

What motivated you to join the War?

When Spain occurred, it was another thing in my political spectrum, and I weighed my decision; what was the consequence of my not going; I wasn’t exactly anxious to go; I was madly in love, physically, but I felt myself alienated from myself because here I was, the big speechmaker in Brownsville on every issue, foreign and domestic. And here came up an issue very quickly, an issue of world importance, and I was just talking about it—whereas previously what I talked about I did. I was a person of thought, word, and action. And now suddenly I became a person of thought and word –[pause] –and I began to feel a deep sense of alienation and shame. Somehow I perceived that if I didn’t go I’d have some very big difficulties with my conscience.

So to me, going to Spain was good judgment. For me, going to Spain was closing a gap that had appeared in myself as a persona, which was tearing me apart. It had nothing to do with courage — we’ll talk about that later. I don’t believe much in that business of courage and valor, because in some ways it may be said that the greater enemy was staying home, and I didn’t have the guts to face up to that. It’s a very funny way to put it, but for me going to Spain was easier than staying home. You won’t find many vets who agree with that. They went to fight fascism; well, fascism was only a concept for me at that time; I didn’t have the slightest idea, a real idea, until I saw it.

Abe’s willingness to explore the intersection of his personal image and aspirations may distinguish him from other vets, who would generally stick with “anti-fascist” and “internationalist” to explain their willingness to go to Spain in 1937.

How much did Hitler factor into the decision to join the war?

By 1942, Hitler’s answer to his “Jewish Question” had solidified into the “Final Solution.” In the conversation, Abe reminds us that this was far less clear in 1937.

You have to keep in mind that in 1936, three years after

The journal of the Botvin Company of the Dombrowski Battalion. The name “BOTVIN” is at the top; the headline—A GEZEGENUNG—suggests “Departure” or a “Farewell” to Spain.

We were aware of that [anti-Semitism], but it didn’t have a tiny particle of the influence that the Holocaust would have when we became aware of it – by ’40, ’41, the liquidation. Before that, it was harassment, economic, political, cultural harassment… the occasional bumping off, but it was not yet the official German policy.

Judenrein [to void Germany and then Europe of Jews, extreme ethnic “cleansing”] was not even an expression yet, even in Mein Kampf he doesn’t talk about Judenrein.

So this issue wasn’t even thought of very much… Except there was a large handful of guys whose primary language was still Jewish –

Yiddish. They asked the International Brigades to form a separate Yiddish-speaking detachment. It was granted. About 200 guys volunteered to be in that. And that was how the Botvin Company was formed.

The Botvin Company of the Polish Dombrowski Battalion was named for Naftali Botvin, a Polish Jew and a Communist who was tried and executed for the murder of a police spy in Lvov in 1925.

Explore more stories: