George Watt, Soldier, 1913-1994

- Why did so many Jews choose to fight in the Spanish Civil War?

- Why did Jews on the left choose to Anglicize their names?

- Why would “a good Jewish boy” choose to become a soldier?

George Watt in 1938 in Spain

George Watt, the man who told me it was time for Jewish vets to “come out of the closet,” explained that he had recently been to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel:

“…where they also talk about the Jewish resistance and justifiably play up the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. But nowhere was it mentioned that there were also Jews who fought Hitler long before. […]

Now whether we all fought out of our Jewishness, or whether that was the primary motive, is not the important question. That will vary with individuals, as you’ll see as you go along. But the fact is that Jews did fight against Hitler long before it was generally accepted, even [before] the general threat of Hitlerism was understood.”

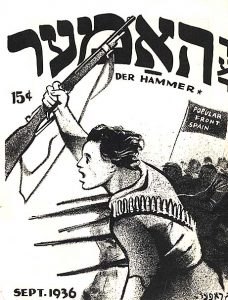

Cover of the American Yiddish magazine, “Der Hammer.” Art by left-wing artist William Gropper.

Indeed, it is only after the fact that Jews who fought in Spain could equate their resistance to Hitler in 1937 with Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto. George Watt, like many of his comrades in Spain, fought fascism twice; first in Spain, and then in the European war which began in September 1939, just six months after the fall of the Spanish Republic. The U.S. again initially maintained neutrality, which only ended with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

George Watt was quick to enlist in the Army Air Corps once the United States joined the war. In November 1943, he parachuted from a flaming B-17 over Belgium and made a remarkable return to England through occupied France—and finally through Franco’s Spain. His memoir, The Comet Connection: Escape from Hitler’s Europe, describes the entire event and the irony of his escape through fascist Spain, which remained neutral during the War.

Why did so many Jews choose to fight in the Spanish Civil War?

In the late 1930s, Jewish American leadership played down the threat to Jews posed by the rise of fascism in Europe; so did the Jewish left. Established Jews “didn’t want to rock the boat.” In addition, as Eli Lederhendler explains in his recent history of American Jewry, “the ‘establishment’ organ, the ‘American Jewish Year Book’ (1939), studiously avoided reporting on the involvement of Jews fighting in Spain, and made only a brief reference to the anti-Jewish tones in Spanish Nationalist propaganda.”

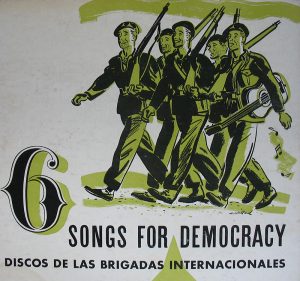

The front cover of a record of internationalist songs, “6 Song for Democracy: Discos de las Brigadas Internacionales”

In fact, only Franco’s Nationalists and their apologists in America were candid about their obsession with Jews. Franco’s vociferous colleague, General Queipo de Llano, announced: “Our war is not a Spanish civil war; it is a war of western civilization against the Jews of the entire world,” an opinion echoed by Father Coughlin and the right-wing Catholic press in the United States.

If, as Watt would explain, anti-Semitism at home and abroad stemmed from the narrow nationalism of the political right, the political left preferred what it always called “internationalism.” One interviewee simply rejected the premise: “Jews in Spain? I didn’t go to Spain as a Jew; I was an internationalist.”

George Watt was a student activist in New York City — first as a Socialist, then as a Communist — before he went to Spain. As a leader in the National Student League, he found himself encouraging other young people to go to Spain while he remained behind. Soon he knew he had to go: “I was afraid our history was going to pass me by.” For George Watt, “our history” certainly included the history of modern Socialism, with its internationalist impulse, but it also meant what he called the “Jewish radical movement,” which for him began with family history.

“I came from a Jewish secular tradition, but Jewish, very distinctly Jewish, and I’ll tell you a little about that. But when we went to Spain we saw ourselves primarily as internationalists. We internalized this feeling of internationalism, that we were citizens of the world.

When Debs [Socialist leader Eugene Debs] was in prison, I remember his famous quote when he lost his citizenship in jail. He said, ‘I’m a citizen of the world,’ and that’s how we saw ourselves. Now it’s true our internationalism was flawed, seriously flawed, because it was an international link to the interests of the Soviet Union. That’s another story. And that, by the way, is part of it, our going too, for those of us who were Communists.

But nevertheless, we did see ourselves subjectively as internationalists. Everyone was my brother and sister. […] And when we went to Spain, we tried to see and feel that we were Spaniards. Not Jews, primarily. Nevertheless, who we were and what led us to this had a lot to do with it, in the case of those of us who were Jews.”

Why did Jews on the left choose to Anglicize their names?

Why did someone raised in “the Jewish radical movement” give himself an Anglo-Saxon name? Some of George Watt’s zest for this project, which he had helped to organize in the first place, may have been the chance that it would give him to better understand and explain some of those contradictions.

“We covered up our Jewishness. We didn’t think of ourselves as Jews. …[S]ome of us had Anglo-Saxon names like mine; mine was an Anglo-Saxon name.”

Of course, the alteration of Jewish names was not confined to activists on the left, but for many active Communists, particularly for those in positions of leadership, it was de rigueur — George Watt cites his friend John Gates, originally Sol Regenstreit, the highest ranking American officer in Spain, along with others.

“There were several elements in it. One was we wanted to hide our Jewish identity to some extent, and that was really in response to anti-Semitism, feeling that people would not follow us.

See, I changed my name when I became a public figure in the Communist movement and I didn’t want my parents to be tarred with this and so on. But that was relatively minor. The main reason was that I had a very Jewish name; my name was Israel Kwatt, and that originally came from my father, who changed his name to Kwatt when he came to this country when he got off the boat. But his father’s name was Kievkavsky, a Polish name. That was the general tendency, to shorten and Americanize names right away. Many people did.

And I further felt that this would be a subject… and people like a friend of mine, Adam Lapin, I remember, one of the leaders in the student movement, said, ‘You can’t.’ I became the executive secretary of the National Student League. […] I was going to Cooper Union. I went to Brooklyn College at first and switched to Cooper Union to study engineering, and then dropped out to become full-time student organizer, and they said, ‘You can’t use the name Izzy Kwatt,’ and so I took on a name which I had already taken on when I joined the Young Communist league.

In those days, there was a romantic style. We aped the Russians. They all had different names, and you had to take on a YCL name or a party name separate from your real name. It was a childish business then, I think, but the atmosphere in the country was different.

For example, you didn’t see a Jewish name in The New York Times on the byline. And my cousin, who finished engineering — and I was going to engineering school — had to change his name to get a job. He couldn’t get a job with a Jewish name. So that was part of it, and they also felt, well, all these people would not follow you.

These were rationalizations. But also part of it was a certain bowing to anti-Semitism, and perhaps certain trying to see ourselves as… well, we sort of went into the closet. How do I say it? I was very much raised in a Jewish tradition. But I wasn’t the only one; that was the trend at the time. You have to see it as a trend. I feel bad about it at this time.”

There is nothing simple in the pattern of changing names on the part of immigrants and their children. One man, Watt’s cousin, changes his name in order to gain access to the middle class, while George seeks access to the working class and, incidentally, wants to adopt some of the luster of his revolutionary models: Stalin (originally Josef Djugashvili), Lenin (originally V. I. Ulyanov) and Trotsky (originally Lev Davidovich Brontstein).

Why would a “good Jewish boy” choose to become a soldier?

None of George Watt’s decisions were sudden. Watt, the man who often quoted the popular Socialist Eugene V. Debs, entered the Depression and the student movement as a Socialist prepared to advance his position through electoral politics. But the violent resistance to the organization of miners in Harlan County, Kentucky, in the spring of 1931 convinced him that nothing shy of revolution would make the system budge. He joined the Young Communist League in 1932.

In a famous photo taken by Robert Capa as the Lincolns leave Spain, Watt marches on the right of Battalion commander Milt Wolff—22 years old at the time. Spain 1938.

Once in Spain as a soldier, Watt never stopped questioning his role there. How would he stand up to combat? Every account of his conduct in both wars indicates that he showed great courage.

But none of this prevented him from asking the inevitable question: “There were many times when I said to myself, ‘What’s a good Jewish boy from the Bronx dong in this combat? What am I doing here? I don’t belong here.” The familiar quip—“What’s a nice Jewish boy…?”—generally suggests that being nice—or “good”—and Jewish means that you have no business being embroiled in whatever activity makes you ask the question in the first place.

When asked to account for the major decisions that he made in this period, George Watt’s response suggests that work as a Socialist, and then as a Communist, and his presence in Spain and again in World War II, were all entwined in his particular experience of being Jewish, that is, in his background in what he calls “the Jewish Socialist milieu.”

“The most important influence on my life was my family values and education in the Jewish Socialist milieu. My father and mother both saw themselves as Socialists, although he never — he was a worker. He worked as a silversmith, jeweler and electro-plater; a metal polisher. He trained in the old country, I mean trained and apprenticed in Europe, in Poland.

Lodz was our original city and we were raised in the tradition of Jewishness, but secular. In other words, they were atheists, both my parents were atheists, although their parents — my mother’s side – was pretty orthodox Jewish. My father’s also, my grandmothers were all religious Jews. But my father had already assimilated Socialist and atheist ideas, even in Poland, but was never very active. But here they read the Forvartz, The Jewish Daily Forward, and we saw ourselves as Socialists. Ever since I was a kid of six years old I had visions of a beautiful world — brotherhood and sisterhood of man, no exploitation and peace and the workers living in a form of Utopia. But there was something else in the family.

Demonstration by the socialist workers’ party the General Jewish Labor Bund, in Poland, 1917. Via Wikimedia Commons.

As long as I can remember, there was a legend in our family around my grandfather, my father’s father. My father’s father was a textile worker, a weaver, in Lodz and he worked in a factory which was owned by a Jewish boss. His factory was the place where they had the first strike of Jewish workers — Lodz — in 1903, at the Shlitsky [Wiślicki] factory in Lodz. And ever since I was a kid my father told a story which was part of our family tradition.

He was not a rabbi, but he was considered very learned and was called Avremele der lamden, Abraham, the learned one, and he was one of the elder workers in the plant, who became active in this strike, and he was one of the leaders of the strike, not the leader, but one of the leaders. And my father always told this story and he said how they were arrested by the Tsarist police because this was Russian Poland then. And he described how he as a six year-old boy watched his father being taken in shackles, and the punishment in those days was they forced you to walk on foot back to your village of origin.See, many of the people living Lodz had immigrated from the smaller outlying surrounding villages into Lodz, where you had industry and they became workers and so on. And he had to move back to his home shtetl in kaytn, in chains. And this was the story I always remembered. And so that was part of our tradition. In other words, my grandfather, the pride that we had, my grandfather had led the first strike of Jewish workers in Lodz. 1903. That was around the time leading up to the 1905 revolution. So that’s part of our tradition.”

“But furthermore, my father loved Yiddish literature and he used to read Sunday mornings. We always read around the table. He would read parts from Sholem Aleichem, he would read from the Kundes, which was a humor magazine… He’d read short stories and sometimes some poetry in Yiddish.

Our first language was Yiddish. I was born soon after my parents arrived in this country, although my father always says I was 100% American because I was conceived here. But soon after they arrived. Yiddish was part of it, and when I was about eight years old I began to go to a Yiddish school, a Workman’s Circle — Arbeter-ring — School. I went to the Yiddish school in Harlem. We lived in East Harlem. There was a combination of Yiddish culture, history.

We saw ourselves as Jews and we spoke Yiddish at home until I went to school. Then we started to speak English. But my parents, their first language always had been Yiddish, and Yiddish was my first language until I started setting out into the streets with other kids. Then we moved to Brooklyn, and there was no immediate Workman’s Circle school in the area, so we ended up in a Sholem Aleichem Shule which is weltekh — secular — and not partisan really.”

“I went on from there to mittlshule. In other words, I actually went beyond that to a Jewish Yiddish high-school [in addition to public school]. This is extra-school activity. In other words, a couple times a week and on weekends. The mittl-shule was really on weekends.

We used to go into the city from Brooklyn to go to this school. And there I developed a circle of friends. There were Communists there, there were Socialists there and there were some of the people who went there later went on to become leaders in the student movement and became Communists, and some became Trotskyists, and some became Socialists. But we studied Jewish history, we were steeped in Jewish history, we studied all the works. I read at that time all of the works of Sholom Aleichem and Mendle Mokher-Sforim, Peretz, the American writers — Raboy and others — in Yiddish. For a short time we were Yiddishists. We tried to speak only Yiddish. So, I was very Jewish at the time.”

Professor Joe Butwin recalls the interview with George Watt:

“Averam the learned” among striking workers in Lodz, 1903. Photo from Image Before My Eyes: A Photographic History of Jewish Life in Poland, 1864-1939, 1977.

Explore more stories: