About Salud y Shalom – From the Interviewer

An encampment of soldiers from the Lincoln Brigade. From the photo collection of Vet Ed Lunding.

Eighty years ago, nearly 3,000 Americans embarked for Europe in order to aid the democratically elected Spanish Republic in its effort to repel a military coup led by Francisco Franco. All but 150 medical workers were breaking the law—that is, the American Neutrality Act—and challenging the legitimacy of a Non-Intervention agreement signed by the major (and several minor) powers. Several of the signatories, most notably Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, broke their part of the bargain and rushed to the aid of Franco’s forces.

The Spanish Republic, while prevented from buying arms from Britain, France or the United States, was able to enlist the aid of the Soviet Union and the Communist movement, which organized voluntary resistance to Franco and fascism. As a result, nearly three-fourths of the American volunteers, who came to be identified as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, were members of the Communist Party or its affiliates. And nearly one-third of the men and women who went to Spain were Jews.

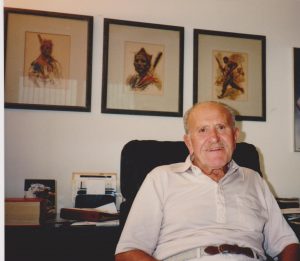

A Veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, paintings of the Spanish Civil War by artist SIM displayed in his office

Twenty-five years ago, between 1992 and 1994, I traveled around the United States from New York to Florida, to Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle, equipped with a cheap tape recorder, a stack of cassettes and a list of addresses provided by the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, or VALB, an organization that had kept the memory of the Spanish Civil War alive since the return of the survivors at the time of Franco’s victory in 1939. One-third of their comrades had died in Spain. Nearly all were wounded; many were branded “premature anti-fascists” afterwards by the U. S. government and were therefore suspect as collaborators with international Communism during the long Cold War that followed the official defeat of fascism in the Second World War, in which many of the Vets also served. By the spring of 1992, when I began to record my conversations with the VALB members (Vets), the Cold War had officially ended with the December 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union.

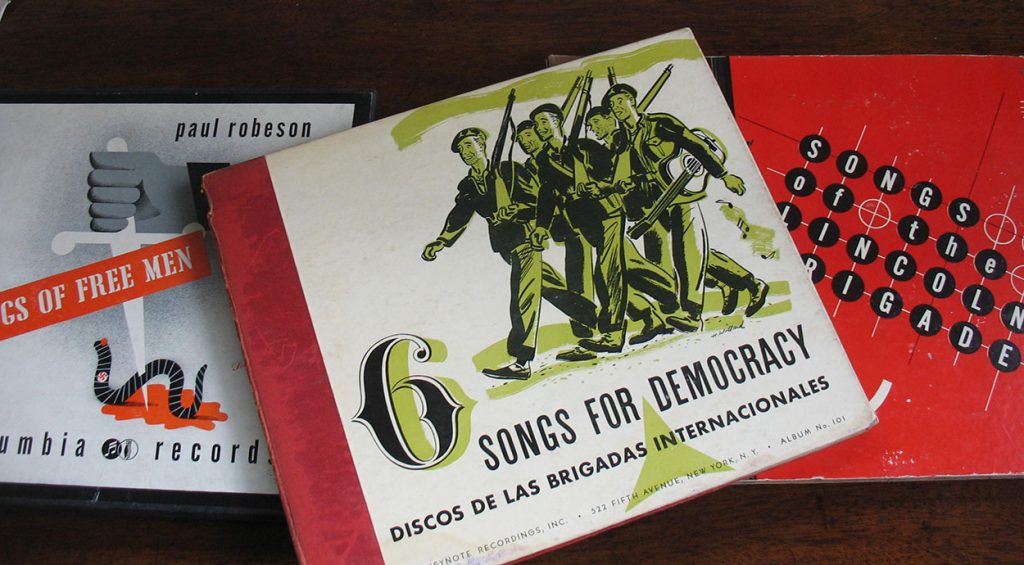

One Vet’s collection of records featuring songs about the Spanish Civil War

The initiative behind my project came largely from the Vets themselves. George Watt, Bill Susman, Abe Osheroff and others invited me to take up the topic. They provided me with the names of other Vets. By 1992, their median age was 80. They had grown up with the Revolution of 1917. Some, in their childhood, had witnessed the Revolution; most were the children of immigrants from Czarist Russia, many of them raised in a tradition of Jewish—and Yiddish-speaking—socialism before they joined the Communist Party in the 1930s. World-wide Depression and the rise of fascism accounted for the enlistment of nearly 100,000 Communist Party members by 1938, when the war in Spain caught the attention of the world.

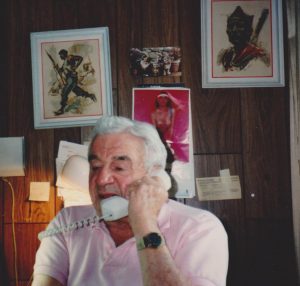

Vet Ed Lending, who also displayed Spanish Civil War paintings in his office

Nearly all of the people I spoke to had left the Party long since, but this was the time for reckoning and reflection. They knew—and I knew—that there wasn’t much time left. When they went to Spain, most of the soldiers, nurses and doctors would have said they were “internationalists” and “anti-fascists”—by no means “premature” ones—but few would have invoked their Jewishness as the reason for putting their lives on the line. Fifty-five years after the fact, few were likely to revise the rationale for going to Spain, but given the chance to talk about their entire lives, many were ready, as one of the organizers explained, to “come out of the closet”—as Jews.

To be sure, I was turned away by some who found my inquiry just as irrelevant at their age as it would have been in their youth. I logged 39 interviews, transcribed half of them, and then for reasons that have more to do with my life than theirs, dropped the project. Contact, conversation, preservation had compelled me all along, but I hadn’t found the right form for the interviews afterwards.

The tapes, the transcripts, the letters that passed back and forth between me and my “old-new” friends went into a file cabinet in my office, where I found them this past year while I was cleaning my Augean stable of an academic office.

Monument to fallen volunteers in the Spanish Civil War on the UW campus

By now, all of my interlocutors have died. I am tempted to invoke the words of the man who gave the Brigade (or, more accurately, the Battalion) its name: In November, 1863, Abraham Lincoln affirmed that “it is for us the living” to sustain the memory of those who fought “in a great civil war.”In 1998, several Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade living in Seattle spearheaded a campaign to build a monument to volunteers from the Lincoln Brigade on the University campus. The monument is not far from Suzzallo Library, where my conversations with Jewish Veterans have been digitized and preserved with the generous support of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and the technical aid and encouragement of Mary St. Germain and her colleagues at the Library.

Now, with the active collaboration of Professors Tony Geist (Spanish and Portuguese, UW) and Edward Baker (Emeritus in Spanish, University of Florida), I intend to edit and publish these recordings. The excerpts here, put online by Kara Schoonmaker and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, are a sample of what will appear in that publication. We derive the title, Salud y Shalom—a familiar greeting and valediction in Spanish and Hebrew or Yiddish—from the habitual valediction in letters that I received from one of the Vets: in health and peace. I could wish for no more.