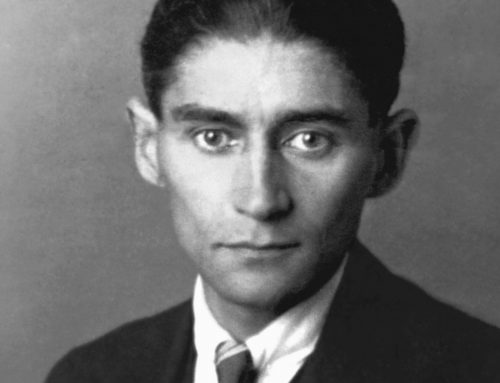

The Eichmann Trial, 1961.

Recently, while reading an article discussing Obama’s use of drone strikes in the War on Terror, I came across a description of these possible targets as “the banality of evil.” The term has its origins with the German-Jewish philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt, who described Nazi officers as quite contrary to what one might expect evil to look like. She was in Jerusalem on assignment at the trial of Otto Adolf Eichmann in 1961, who had been kidnapped by the Mossad in Argentina and, drugged and dressed as an El Al crewmember, taken to Israel and put on trial. The assignment was for the The New Yorker and the trial was already controversial. Many in the international community spoke out against the kidnapping, in favor of a trial in the International Court of Justice at the Hague. Even the American Jewish Committee asked David Ben-Gurion to allow Germany or the ICJ to prosecute Eichmann.

Nonetheless, Eichmann was to be tried and Arendt was hired to cover the story, despite jokes among some editors that “academics are terrible with deadlines.” Her first impressions, later published in Eichmann In Jerusalem, were perhaps the most famous. She writes that “the man in the glass booth” was “nicht einmal unheimlich — not even sinister.” She argues that “The deeds were monstrous, but the doer … was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous.” In other words, here we had her infamous term the banality of evil.

The 2012 film Hannah Arendt recently played at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) produced by German filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta. The film follows Arendt’s assignment to cover the Eichmann trial, and interjects the primary narrative with flashbacks to Arendt’s past, including her involvements with Martin Heidegger before she fled Germany and arrived in the United States in 1941. (As a side note, there is an excellent play called Hannah and Martin about this very relationship. A particularly dramatic encounter from the play: Arendt walks into Heidegger’s office. He looks up at her from his stack of incomprehensible German philosophy. She tells him: “I want you to teach me how to think.”)

The film does an excellent job of recasting philosophy in lay language. As one of the New Yorker editors points out to his Editor-in-Chief, Hannah Arendt became famous for being the first to contextualize totalitarianism as a product of the West. She traces the development of anti-Semitism and racism as a product of “New Imperialism,” whose ultimate expression was the modern nation-state. The Nazi project, in other words, was a modern, Western project from this perspective. Scholars have long struggled with their Arendtian inheritance; please see Norman Naimark’s Fires of Hatred and Zygmunt Bauman’s Modernity and the Holocaust.

For this young historian, the banality of evil and her work on totalitarianism are the most memorable aspects of Hannah Arendt’s thought. However, many remember her for other arguments she made in Eichmann In Jerusalem. In particular, she criticized Jewish collaborators in Eastern Europe during the Shoah. This, together with her critique of Zionism (which is really a critique of nationalism), as well as her staunch atheism, made her a complicated figure, especially for the Jewish community in the post-World War II moment. In the film, we see how Arendt’s friends in New York and in Israel turned away from her after Eichmann was published. The audience bears witness to the often lonely life of the intellectual, yet we also see a kind of staunch arrogance.

Arendt stood by her arguments until she died in 1975. One of the film’s most poignant scenes is a lecture at Bard College, in which she points out that the crimes against the Jews were a crime against all humanity, a point in which we see von Trotta’s position that, whilst arrogant, Arendt was largely misunderstood. A scholarly crossover work by acclaimed historian Deborah E. Lipstadt, The Eichmann Trial, tackles the daunting task of understanding these critiques and Arendt’s arguments in their due context.

Arendt’s depiction of Eichmann is a warning: she portrays him as a “conformist, as a “leaf in the whirlwind of time.” Indeed, it is a terrifying lesson that we learned in the twentieth century, that “the sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.” While complex and problematic in its own way, Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil is actually well-suited to today’s increasingly complicated political climate.

[1] Lipstadt, Deborah E. The Eichmann Trial. New York: Nextbook/Schocken, 2011.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)