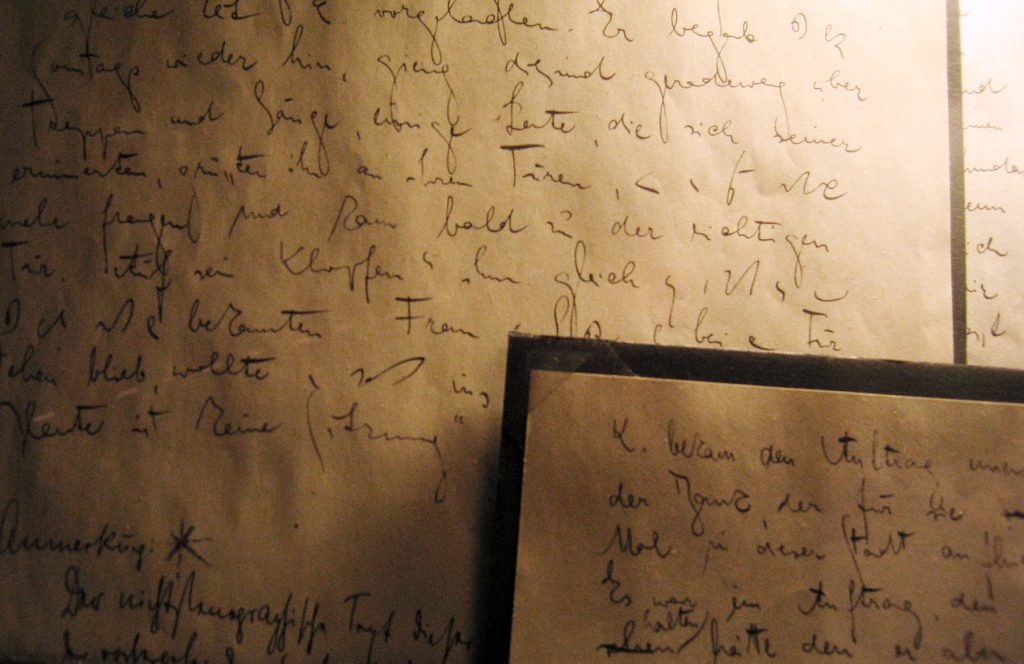

Franz Kafka’s handwritten manuscript of “The Trial,” displayed in the Kafka Museum in Prague. Photo by Pablo Sanchez Martin.

By Aaron Carpenter

How could you express yourself as a Jew in German at a time when foreign words and ideas were suppressed? This was the question that plagued writer Franz Kafka in turn-of-the-century Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where German and Czech were the official languages.

In a letter to his friend, fellow writer Max Brod, Kafka wrote that most Jews who wanted to write in German “stand with one foot in their father’s Jewishness and find no firm footing with the other.”

My doctoral research examines how writers of a minority group use the language of the majority to tell a story that the majority doesn’t want to hear. I start with examining how Kafka expressed himself as a Jew in a society that was often hostile to its Jewish members.

Kafka began to find a solution to this question through the Yiddish language.

Kafka’s estrangement from Judaism

Kafka’s parents grew up speaking a dialect of Yiddish in the countryside of southern Bohemia (in the present-day Czech Republic, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). When they moved to the large city of Prague, his parents disregarded Jewish customs and even looked down on Jewish culture.

Kafka himself learned to internalize such negative views of Jews. In 1914, he wrote in his diary: “What do I have in common with Jews? I barely have anything in common with myself.”

Actress Flora Klug, a member of Löwy’s acting troupe, circa 1912. Via the Digital Yiddish Theater Project.

Kafka found a solution when he went to see a performance by Yitzhak Löwy’s Yiddish acting troupe at the Café Savoy in Prague. In a diary entry dated October 6, 1911, Kafka described how he and the other audience members were enthralled when Yiddish actor Flora Klug sang about her “jüdische Kinderloch” (little Jewish children), which drew the audience of German-speaking Jews to her as an ersatz mother figure.

Kafka was fascinated by these actors, calling them “people who are Jews in an especially pure form.” This resulted in an 11-month intensive study of Yiddish language and culture and many return trips to the theater. As a result, he and Löwy became friends.

Kafka’s relationship with Yiddish

Kafka’s study of Yiddish culminated in February 1912, when he gave a speech on Yiddish for a fundraising event that he had organized to raise money for Löwy’s acting troupe.

In his speech, Kafka associates what he called the “liveliness” of Yiddish with its grammar and vocabulary, which largely comes from German, but which is also strongly influenced by Hebrew, Slavic, and other languages.

Yiddish and German separated as languages between the 12th and 15th centuries. Because Yiddish retains many words and grammatical structures that are no longer found in German today, the language can sound archaic to German speakers.

Franz Kafka, circa 1923. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Kafka told his audience: If you listen to Yiddish, “there are active in yourselves forces and associations with forces that enable you to understand intuitively.” You understand Yiddish not just from the language, but through seeing Yiddish culture performed: “[…] Yiddish is everything, the words, the Chasidic melody, and the essential character of this East European actor himself […].” In order to do this, you had to let go of what he called a “fear” of Yiddish.

However, Kafka himself never fully let go of his fear of, or prejudices against, Yiddish. He saw himself as the guardian of German grammar and looked at Lowy’s unabashedly Yiddish-influenced German with both fascination and smugness. He often sent his then-fiancé Felice Bauer copies of Löwy’s letters. Once he wrote: “Could you actually read Löwy’s letter, that I sent you for Sunday? He’s playing in Berlin on Sunday, at least I think that’s what I could make out from his letter […]“

In his writing, Löwy often followed Yiddish, rather than German, grammar rules. In one example, when Löwy describes the street Felice Bauer lives on, he wrote: “Prenzlower Allee. Welche hat viele Seitengässchen” (“Prenzlauer Alley. Which has many side streets”). Löwy places “hat” in the second position, whereas in German it would go to the end of the sentence (German: “Prenzlauer Allee, welche viele Seitengässchen hat”).

When Löwy asked Kafka to edit his article, “On the Jewish Theater,” Kafka gladly agreed. But there was a problem. Writing to his friend Max Brod in September 1917, Kafka provided an example of Löwy’s German: “frackierte Herren und negligierte Damen” (“tuxedoed men and ballgowned ladies”) and comments that the phrase was “excellently put, but the German language balks.” Kafka balked at the bad grammar, as he balked at Löwy’s letters.

Kafka had to find a way to balance Yiddish’s “liveliness” with his fixation on proper grammar.

“On the Jewish Theater”

In his article, which Kafka edited and which can be found in Kafka’s posthumous works, Löwy narrates how he first became enthralled with theater through the holiday Purim, when Jews would dress up and perform the biblical story of Queen Esther. He then describes going to the Polish and then Yiddish theaters in Warsaw (in present-day Poland). The article ends with the Löwy’s pious father warning him against running off to join the theater. (Read my translation of Löwy’s full article, “On the Jewish Theater.”)

Yitzhak Löwy as a young man. Via the Embassy of the Czech Republic’s Franz Kafka exhibit.

In the edited version of the article, Kafka kept several Hebrew and Yiddish words. As scholar Jeffrey A. Grossman explains, including Hebrew words when translating Yiddish into German helps to exoticize the language and recreates the feeling and structure of Yiddish. This helped Kafka to retain the article’s Yiddish context and feel without sacrificing “correct” German grammar.

Yiddish wordplay in German

In Löwy’s account, as edited by Kafka, when their son first expresses interest in the theater, his parents declare the theater to be “trefe, nothing but chaser.” Trefe is a term for food prohibited by Jewish dietary laws, i.e., not kosher, and chaser, chazir, is a word for a pig or a greedy person. Chazir tref is a Yiddish phrase for something or someone that goes against Jewish law or tradition.

After Löwy’s parents learn that he has been going to the theater, they have a serious talk with him. Löwy writes of that moment: “Instinctively, I felt like a kasche was going to be cooked for me.” In Yiddish, עשאַק is pronounced either as kesche (a religious question) or kasche (buckwheat groats). This pun shows that a question is going to be cooked up for Löwy to find out if he was doing something that he had been forbidden to do.

At the end of the story, Löwy’s father commands his son: “Mein Kind, gedenk, das wird Dich weit, sehr weit führen” (“My son, think, this will take you far, very far away”).

Gedenk is the imperative form of the verb gedenken, to remember, which is an antiquated verb by Kafka’s time. The line represents how a Yiddish speaker might sound antiquated to some German speakers.

Reflecting on Kafka’s relationship with Yiddish

While including Hebrew words in German does reproduce the “liveliness” of Yiddish, Kafka could not help but “balk” at the inclusion of the foreign in the language he adored. In contrast to the Yiddish-inflected German of Löwy’s article, Kafka’s own writings were composed in conventional German only.

Nevertheless, Löwy and the other Yiddish actors helped Kafka see a new way of expressing himself as a Jew, through distinctively Jewish language and art.

Read my translation of Yitzhak Löwy’s full essay, “On the Jewish Theater,” edited by Franz Kafka.

Aaron Carpenter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of German Studies at the University of Washington and is the 2022-2023 Pamela and Robert Center Fellow in Jewish Studies. His main areas of academic interest are minority literature in Austria and Germany, as well as literature from German minority groups in non-German-speaking regions, such as South Tyrol in Italy. His dissertation examines how writers from the former Yugoslavia and Austria use foreign words to name and discuss traumatic experiences. While his area of focus is on authors primarily from the former Yugoslavia, the theoretical basis for this work is grounded in the writing of German Jewish thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. Before coming to the University of Washington, Aaron taught English in Qingdao, China, and Innsbruck, Austria, as well as working as a technical writer with Hewlett-Packard.

Aaron Carpenter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of German Studies at the University of Washington and is the 2022-2023 Pamela and Robert Center Fellow in Jewish Studies. His main areas of academic interest are minority literature in Austria and Germany, as well as literature from German minority groups in non-German-speaking regions, such as South Tyrol in Italy. His dissertation examines how writers from the former Yugoslavia and Austria use foreign words to name and discuss traumatic experiences. While his area of focus is on authors primarily from the former Yugoslavia, the theoretical basis for this work is grounded in the writing of German Jewish thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. Before coming to the University of Washington, Aaron taught English in Qingdao, China, and Innsbruck, Austria, as well as working as a technical writer with Hewlett-Packard.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

![Inaugural “Muestros Artistas” [Our Artists] Sephardic Arts Symposium](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/UWJS_Artists-019-500x383.jpg)

Leave A Comment