Fresco by Filippino Lippi at the basilica of Santa Maria Novella depicting Adam sheltering a child from Lilith. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Elizabeth Férauge

The subgenre of religious horror in the West has been largely dominated by Christianity and its associated morals and ethics, to the point that some have pointed out these films can function as a kind of Christian propaganda.

As Molly Adams writes in her introductory essay to the “Jewish Book of Horror,” this “sheer dominance of this vein of horror has one crucial downside: it gives one group, one mindset, a monopoly on fear.”

However, Judaism is becoming more common in the box office, leading some to wonder if we’ve entered a new phase of Jewish horror.

Jewish horror, past and present

The recent film “The Vigil,” released in 2019 and directed by Keith Thomas, was a turning point in the genre, in that it paved the way for Jewish horror in the popular imagination: it was one of the first horror films to directly advertise its roots as “steeped in ancient Jewish lore and demonology.” However, it was far from the first iteration of Judaism in horror films.

Jewish folktales of the supernatural have provided ample fodder for horror tales told from the first decades of the twentieth century onwards. The best-known motifs are dybbuks (“Der Dibuk,” 1937; “The Unborn,” 2009; “The Possession,” 2012) and golems (“The Golem,” 1920; “The Golem,” 2018).

On the other hand, while Jewish ghosts and monsters have been present in the history of horror, it has also been the case that Judaism and Jewish markers of identity have largely functioned as foils for a primarily Christian story, using, in film scholar Mikel Koven’s words, “Jewish drag.”

What is different about the films being released more recently is that they not only make extensive use of Jewish religious and folkloric traditions, they do so in an explicitly Jewish cosmology (or worldview).

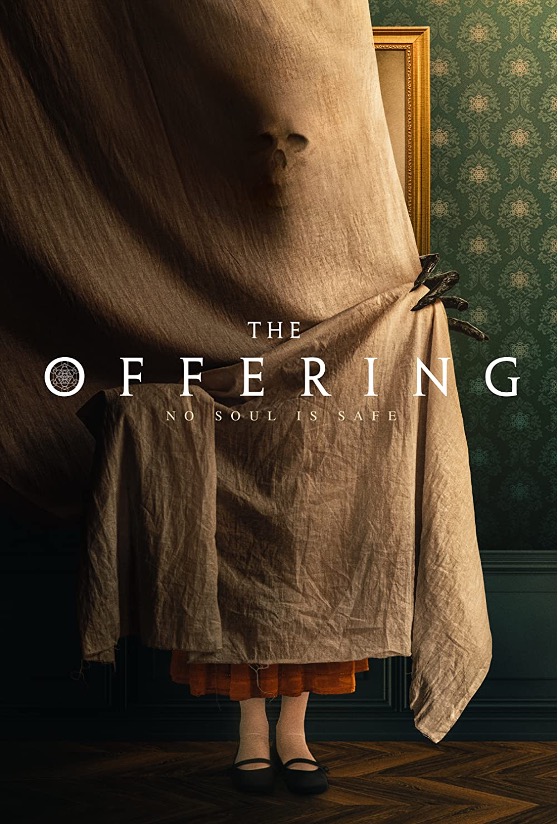

“The Offering”: An ancient demon in a new tale

Oliver Park’s film “The Offering” (2022) has been termed “Jewish horror served up raw,” and “Jewish horror with deeper themes.” A grieving widower, desperate to bring his wife back from the dead, summons what he believes to be an angel (“Martiel”) but what turns out to be the demon Abyzou, who begins demanding that he bring her children to devour in return for his wife: “a life… for your wife.”

Oliver Park’s film “The Offering” (2022) has been termed “Jewish horror served up raw,” and “Jewish horror with deeper themes.” A grieving widower, desperate to bring his wife back from the dead, summons what he believes to be an angel (“Martiel”) but what turns out to be the demon Abyzou, who begins demanding that he bring her children to devour in return for his wife: “a life… for your wife.”

Filled with remorse, he traps Abyzou in his body in a ritual suicide (in a stunning reversal of a typical exorcism, which usually aims at expelling the demon as far away from the body as possible). His corpse is brought to a funeral home, where, coincidentally, the director’s son returns after a long absence, with his heavily pregnant wife — to whom the demon turns her attention.

Abyzou has been haunting the Jewish horror film and preying on its mothers and children since as early as 2012 in Ole Bornedal’s “The Possession,” and evidently will continue to do so as a third film, “Abyzou: Taker of Children” (directed by Jordan Pacheco), is currently in production. It seems that, in true monstrous fashion, Abyzou just keeps coming back.

Bronze amulet depicting the demon Abyzou kneeling and whipped by the archangel Raphael. Early Byzantine era (6th/7th century CE). Via Wikimedia Commons.

Who is the demon(ess) Abyzou?

“The Offering” helpfully contextualizes Abyzou in its opening text:

“In the myths of the Near East and Europe, there is one terrifying female demon, depicted in amulets, paintings, and stories from as early as 1st century AD. She has dozens of names in multiple languages and religions but carries only one horrifying attribute: the taker of children.”

As far as context goes, this is fairly accurate. Abyzou is first mentioned in The Testament of Solomon, a 1st century CE pseudepigraphal text:

“I am called among men Obizuth; and by night I sleep not, but go my rounds over all the world, and visit women in childbirth. And divining the hour I take my stand; and if I am lucky, I strangle the child. But if not, I retire to another place. For I cannot for a single night retire unsuccessful. For I am a fierce spirit, of myriad names and many shapes. And now hither, now thither, I roam. (…) For I have no work other than the destruction of children.”

Many amulets and incantations with protective functions have been found from the Early Byzantine period, usually depicting Abyzou being subdued by King Solomon or the angel Raphael. Miscarriages, traumatic childbirths, and sudden infant deaths were attributed to her.

Connections with Lilith

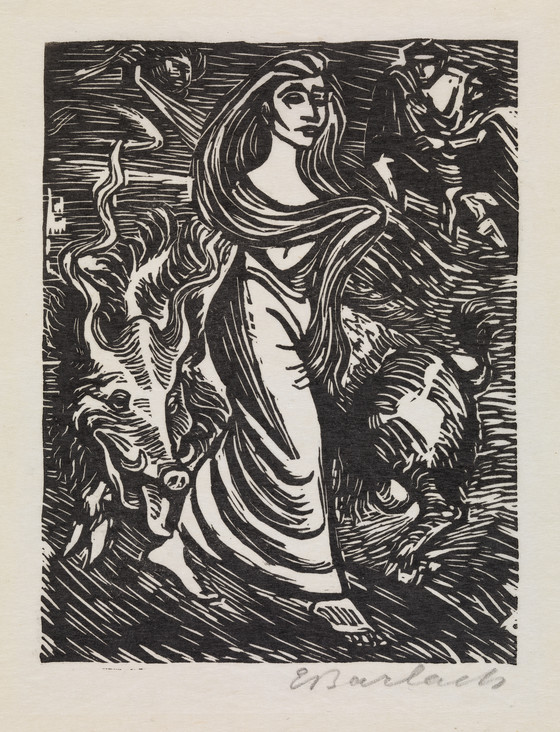

“Lilith, Adam’s first wife.” Woodcut by Ernst Barlach, 1923, Germany. Via the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Scholars have identified Abyzou/Obizuth with other female child-killing demons: Tiamat from ancient Babylonia, Lamashtu from Mesopotamia, Antaura and Lamia from the Greco-Roman world, Gello/Gillo from Byzantium, and, likely the most familiar one to readers, infamous Lilith – incidentally, also featured in Jewish horror film Lullaby (2022), where she, true to her archetype, preys on children.

Mother of demons, the original vampire, the first feminist femme fatale, Lilith is omnipresent in popular culture and has had tremendous importance for Jewish feminism, particularly since Judith Plaskow’s alternative biblical fable “The Coming of Lilith.”

While studies have examined Lilith’s importance for contemporary feminist movements and her presence in popular culture more broadly, they tend to emphasize her seductive, sexual femme fatale iteration, while neglecting her tendencies towards child-killing – this aspect has been relegated to the realm of horror, it seems. But why?

Horror: Bringing ancient traditions to modern stories

One of the shared functions of religion and horror is storytelling. As scholar of religion Douglas Cowan shares in his book “Sacred Terror,” religious motifs and myths used in horror films have been necessarily transformed or adapted for a contemporary context — they adapt and build on ancient traditions and make them relevant for modern times.

Pregnancy, childbirth, and caring for a small vulnerable living human are terrifying enough on their own without adding the threat of demonic oppression to the mix. But indeed, it is these very terrifying and dangerous times that are best served by the folktales and rituals inspired by them.

Most tales of the supernatural and associated protective rituals are centered around lifecycle events – turning points in a person’s life, such as birth, pregnancy, marriage, and death.

Scholars of the ancient world have argued that the stories of the child-killing demoness Abyzou/Gillo/Lamia/Lilith roaming through villages and towns seeking children to devour were a way to explain the unexplainable, make sense of the nonsensical, and provide a more tangible threat to guard and fight back against.

“The Offering” and other Jewish horror films that make use of these traditions participate in this tradition of retelling timeless stories for a new context. In doing so, horror inevitably holds up a mirror, reflecting the darkest parts of our history.

Elizabeth Férauge is a second-year comparative religion M.A. student at the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, and a predoctoral instructor in the Comparative History of Ideas department, where she teaches an undergraduate course on religion and horror films. Before coming to the UW, Elizabeth earned her B.A. in psychology from McGill University, and her M.A. in counseling psychology from The Seattle School of Theology and Psychology, where she currently works as an assistant instructor. Her academic interests lie at the intersection of religious studies and death studies, studying the ways in which concepts of the body and personhood influence afterlife beliefs and mortuary traditions. She is also interested in the afterlives of ancient religions, when ancient themes transcend time and medium to become relevant in contemporary expressions: in literature, popular culture, film, and social justice. She is the 2022-2023 Max Sarason Fellow in Jewish Studies.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

![Inaugural “Muestros Artistas” [Our Artists] Sephardic Arts Symposium](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/UWJS_Artists-019-500x383.jpg)

Leave A Comment