Younes, an Algerian émigré in France, runs to save a young Jewish orphan. https://www.coveringmedia.com/

Free Men, the latest film from the Moroccan-French director Ismaël Ferroukhi (Le Grand Voyage, 2004) screened at the Seattle Jewish Film Festival last week. The film has received much attention recently for its treatment of a relatively unknown moment in the history of World War II, when the Grand Paris Mosque, located just steps from the Latin Quarter, helped to conceal and actively save Jews in Vichy France. The film claims that the mosque rector, Si Khaddour Ben Ghabrit, and the mosque Immam together concealed both the political activity of the Resistance and their efforts to save French Jews that all took place within the Mosque’s sacred courtyards and prayer rooms. The historical actors depicted in the film ultimately supplied false documentation for several North African Jews living in German-occupied France, helping to conceal their identity and allowing them to “pass” as Muslim. Shared language (Arabic), dietary laws, and a tradition of ritual circumcision made passing between Muslim and Jewish identities possible in Vichy France.

The film follows Younes, a Muslim man from Algeria, who moves to Paris to work in a factory. He soon turns to the black market to send remittance pay back home to Algeria, peddling cigarettes, alcohol, and even traditional instruments. After a raid on his apartment intended to crack down on illegal North African immigrants, he is coerced by the Chief of Police into spying on the inner workings of Ghabrit and the Paris Mosque. However, Younes is soon discovered by the German occupiers and becomes an accessory, and later an accomplice, to the French Resistance. Along the way, he befriends a Jewish singer from Algeria, Salim Halali (Mahmud Shalaby), one of the recipients of false Muslim identification cards from the mosque. After an arrest and allegations by the German occupiers, he is forced to prove his Muslim “race” (as the Nazis understood it) by showing his “father’s” gravesite at the Muslim cemetery in Paris (Ghabrit’s idea: “No one will doubt you are a Muslim if your father is buried at Bobigny”).

The most touching moment of the film is perhaps when Younes arrives at an apartment building to deliver false identification documents to a Jewish family. He arrives too late–the family had been arrested that morning–but their two young children were hidden with a neighbor. Younes takes the children back to the mosque, and, after some officials make objections, Ghabrit sternly silences them: “They are our children.” The entire mosque later moves to protect and evacuate the children, including one scene where the Immam, leading prayers on Eid (a major holiday), directs his congregants into the courtyard so that Younes and the children may be lost in the crowd and concealed from the German officers who had entered the mosque.

Because the question of Jews in the mosque is so salient, it is easy to forget that there are other fascinating historical impulses and narratives at work in Free Men, particularly surrounding the colonial struggles of North Africa and the Middle East. The film wanders through glimpses of unions, communists, French Resistance, and Algerian Liberation Movements. We witness the anti-colonial speeches and writings that invoke the intellectual genealogies of the (Cartesian) Enlightement. We hear a narrative of liberation in the background, describing all “races” as equals in a struggle, as they play out in the politicized prayer rooms-turned-meeting rooms of the mosque. Indeed, there is no separation between sacred and secular in this film. Younes wears French clothing in the mosque; Ghabrit attends political events and meets with German officers always wearing his Immam’s robes. We see the way in which everyday life, especially religious life, was politicized and infused with the ideologies not only of the occupiers, but also of those resisting.

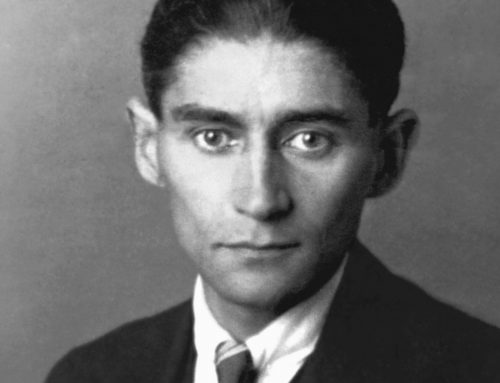

Si Khaddour Ben Ghabrit, the mosque rector, walks through the courtyard with a German Officer

There is also a fascinating element of surveillance in the Foucauldian sense: there is a feeling that everyone is being watched (Foucault, by the way, came of age in Vichy France). The Germans are watching the Muslims and the Jews, the French police watch the communists and the immigrants, the rector watches over his congregation. Actors are constantly looking over their shoulders, and the structure of the mosque, with its Andalusian courtyard, lends itself perfectly to the infamous panopticon.

Ferroukhi undertook a daunting directorial task, and despite some of its shortcomings on the historical front, Free Men is still a magnificent cultural artifact. It gives us wonderful insight into the highly ethnically, religiously, and politically diverse world of the Metropole. The Grand Paris Mosque stands as a microcosm of all these identities, exemplifying the necessity of recovering moments of altruism during the darkest of historical moments.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)