“I didn’t want to write another book about the Holocaust. I wanted to write about survival. This is a story about what it means to have survived and to try and go on living.” –Göran Rosenberg

A Post-War Excavation

Goran Rosenberg’s A Brief Stop on the Road from Auschwitz has found a broad audience in Sweden and around the world. Photograph by Hannah Pressman.

In A Brief Stop on the Road from Auschwitz, now available in English translation from Other Press, the Swedish journalist Göran Rosenberg describes his father’s experience of surviving his Holocaust survival. In prose that alternates between clinical details of wartime atrocities and lyrical depictions of his early childhood, Rosenberg conveys the psychological price of living through a nightmare.

Rosenberg read excerpts from A Brief Stop and described his artistic process during a mid-November visit to the UW cosponsored by the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and the Department of Scandinavian Studies. As the rain poured heavily outside the Husky Union Building, Rosenberg defined the book as “an excavation” into his parents’ post-war lives. Born in 1948 and growing up as the only child of two Holocaust survivors, Rosenberg lacked that thing that parents and children usually have in common–a past of shared memories. He therefore tried, through exhaustive research and emotionally wrenching reconstruction, to recreate that part of his parents’ life to which he did not have access as a child. “There were two different universes–the child’s and the father’s. My goal was to try and bring my father back, to find him again,” Rosenberg explained to the gathered crowd.

Categorizing A Brief Stop is challenging. Is it a childhood memoir, a biography, or a family portrait? Rosenberg said, “It is a childhood memoir about a child trying to bring his father back. It is a childhood memoir of another person. This book is a resurrection of my father in a way. The reader gets to know his existential situation. It is the most private book that I have written.” From the survival of the Lodz ghetto to Auschwitz-Birkenau, slave labor camps, and transports, his father ended up in the town of Södertälje, where he sought work and eventually sent for his wife to join him. That small town, itself “a wrecked planners’ dream,” comes to represent the disappoints of his parents’ new life.

I was particularly struck by the second-person address that dominates the book’s prose, which allows Rosenberg to address his father directly in passages such as this: “I’m the one who needs every fragment that can possibly be procured, so I don’t lose sight of you. A fragment that can’t be erased, edited, denied, explained away, destroyed. A date. A list. A registration card. A photograph. The exact names and numbers of the days when your world is liquidated” (52).

Asked whether this mode dialogue was a stylistic choice from the beginning or a form that evolved, Rosenberg responded, “That was the form that it had to have. It was not really a dialogue because he doesn’t say much back, though I do imagine him speaking.”

Sweden During and After World War II

Aerial view of central Södertälje, ca. the 1960s. Södertälje lies southwest of Stockholm. The city’s canal connects Lake Mälaren to the Baltic Sea.

The Swedish-Jewish experience has not been at the forefront of Holocaust literature or scholarly analyses of World War II. To help fill in that gap, Rosenberg began his talk by sketching in the background history about the tension in Swedish culture between intolerance and openness towards Jews and minority groups. Sweden’s political position in the war further complicated the situation. He said, “Sweden was not in the war so it didn’t quite have a direct connection to the events. There was a kind of ambiguity” about how Sweden should conduct itself towards individual victims of Nazi persecution.

Perhaps surprisingly, given this checkered legacy, A Brief Stop on the Road from Auschwitz has been extremely popular in Sweden, selling 200,000 copies in that country and capturing France’s 2014 Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger. Asked if he had a theory about why the book has resonated so broadly, Rosenberg admitted that he, too, was surprised by the global audience that has emerged for his book, then offered this thought: “It is not just a Jewish book. It is about the perpetrators and the bystanders around the world, too. It makes people reflect on their own humanness. This is a legacy of European civilization that should stay with everybody.”

Despite the book’s universal reach, it is ultimately the specificity of home and family that give A Brief Stop the suckerpunch of enormous sorrow that lingers long after the final page. Rosenberg opens his book by describing the Place and the Child, proper nouns (along with the Bridge and the Canal, pictured above) that grant his prose the flavor of a fable. His house near the Södertälje train station was the site of the formative memories that he tries to recapture in this passage that he read aloud to his Seattle audience:

“This is it; this is the Place. This is where my world assumes its first colors, lights, smells, sounds, voices, gestures, names, and words. . . . This is the Place that will continue to form me even when I’m convinced that I’ve formed myself” (13).

In the book’s early sections about his childhood, Rosenberg’s passages on the role of language stand among the most exceptional reflections on verbal subjectivity I’ve encountered in Jewish autobiographical writing. He wonders, for example, about what happened to his father’s native languages of Polish and Yiddish: “Where did he hide them? Are they perching like lost birds in his memory, waiting to be discovered?” (40). He describes his magical moments of “put

This phenomenon is common to children of Holocaust survivors, known as the second-generation survivors. Psychologists and literary scholars alike have studied the second generation of the Holocaust (known sometimes as 2G) in order to understand how traumatic memories are transmitted within family units. Marianne Hirsch’s concept of post-memory, for example, gives us a way to understand how children can remember a trauma that happened to their parents and therefore preceded their birth. Erin McGlothlin’s 2006 study, Second-Generation Holocaust Literature, looks at writers from Art Spiegelman to Patrick Modiano (last year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature) to understand the post-Holocaust “aftershocks” afflicting children of survivors.

A Brief Stop on the Road from Auschwitz demonstrates that sense of emotional aftershock that, clearly, continues to haunt this child of survivors, seventy years after the events themselves took place.

Göran Rosenberg on Surviving the Survival

The Swedish journalist Göran Rosenberg. Photo credit: Cato Lein.

When Rosenberg presented his book at the UW last month, he concluded by reading from the book’s final section, “The Shadows,” wherein he reflects on the irony of the term “survivor”: “People who survive go on living, they don’t go on surviving. Surviving is normally not a continuous state but a momentary one” (277). Yet for Holocaust survivors like Rosenberg’s father, their state of still being alive continued to be the defining fact of their postwar identities in the eyes of others. That led to the inevitable, central tension in his father’s life: “…the step from surviving to living demands this apparently paradoxical combination of individual repression and collective remembrance” (279).

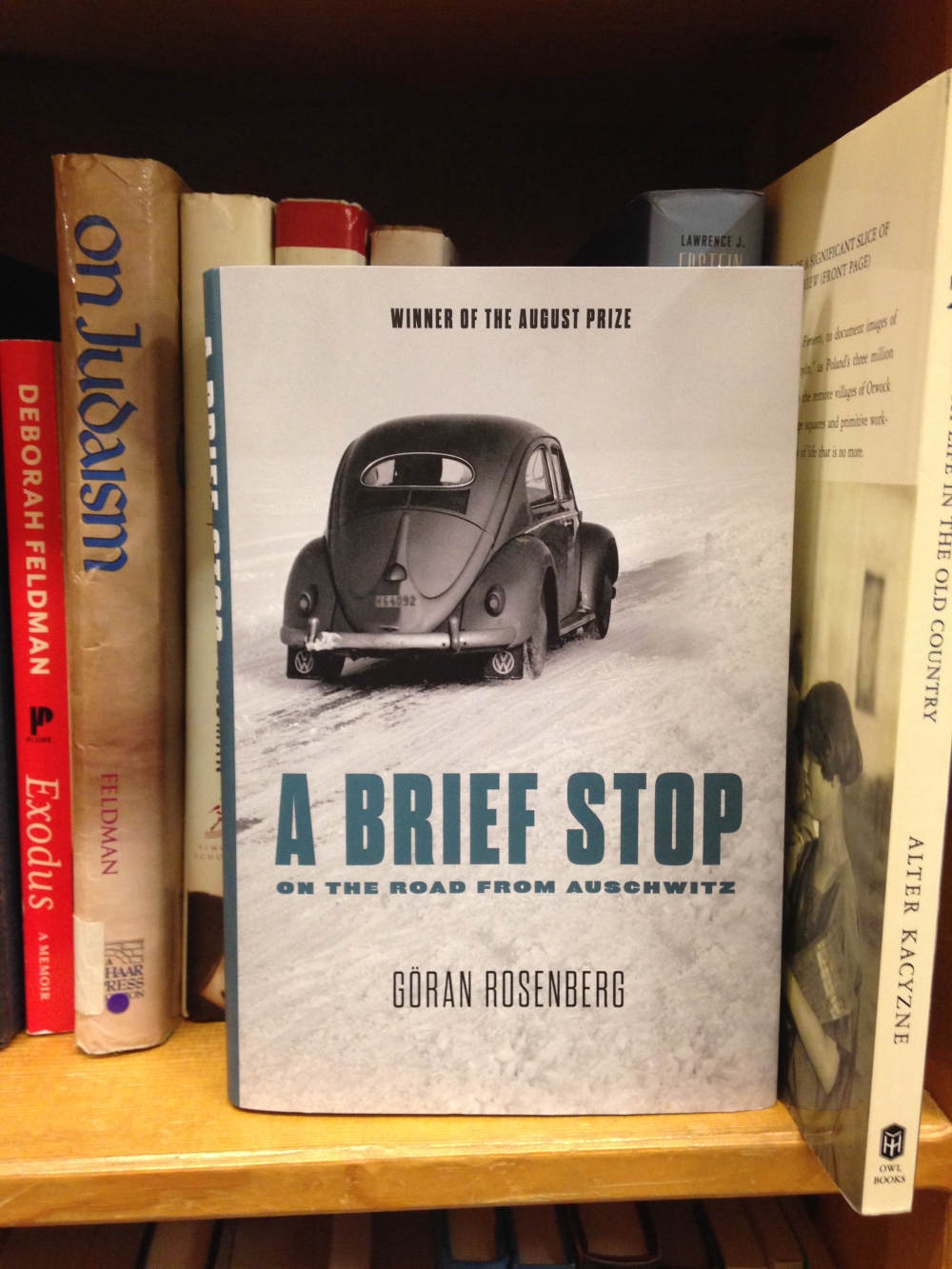

The book’s cover, a photograph of a 1955 black Volkswagen, becomes all the more poignant when contextualized within the difficulties that Rosenberg’s father faced on the journey to survive his own survival. Rosenberg writes of the car as something that would have been an unthinkable luxury during the war, “but in the new life in the new world, so many things that were unthinkable only yesterday are not anymore.” Purchasing the car—“the latest model”—was a sign of hope, a symbol that now, after half a decade spent desperately fleeing what seemed like inevitable death, his parents could now drive “nowhere in particular to unpack a picnic basket or a deck chair, or just see the world through the car window” (234-235).

Yet it wasn’t enough. The Project, as Rosenberg names his father’s chain of good-faith entrepreneurial initiatives, fell short. Despite the attempt to rebuild a semblance of normal life with his wife and two children, his father was unable to continue surviving.

Decades later, Göran Rosenberg, as a grown man, was compelled to get in his own car and painstakingly retrace his father’s wartime journeys from one hellish landscape to another, until he arrived at the small Swedish town and the house by the railroad station that his father had hoped would bring him peace. Part travel log, part elegy, part moral indictment, part howl of anguish, Rosenberg’s book is an evocative memoir captures the movement of two restless souls towards each other on the road from Auschwitz.