Before going to college, I withheld nachas from my grandparents by going to Professional Umpire Academy in Kissimmee, Florida (perhaps the only leaflet smaller than the one in Airplane! for professional Jewish umpires). My roommate for a month and a half was a proud Cajun from Louisiana. He was the first Cajun I had ever met, and I was the first Jew he had ever met. It seemed simple enough to understand what it meant to say that he was Cajun. He found no problem understanding what my Judaism meant, either – “you are part of the Hebrew people.”

Huh? I argued with him – Judaism isn’t my race, it’s my religion. I told him that if he really wanted, he, too, could be Jewish. He pointed out that Biblically the Jews were a people. At the moment of contention, he was busy reading a Bible while I was reading about the infield fly rule.

Looking back on it, I was pretty ignorant to never realize the existence of this question. What does it mean when I say “I’m a Jew”? What is my connection to those who identify themselves the same way, both present and past? Well, let’s go ahead and explore that question – genetically (I should say that, since Umpire Academy, I have also been alerted to the presence of other arguments about Judaism as a nation/ethnicity, which is a whole other debate I won’t go into now).

While genetic information is frequently associated with medical research, it also produces a wealth of historical data. After all, simple rules of inheritance dictate that your genome is a mashed up record of who got jiggy with whom. Rapid DNA sequencing and complex statistical simulations are the newest tools added to the workbench of those interested in the history and demography human populations, and enable us to approximate ancestries.

Two recent studies, one headed by Harry Ostrer out of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and one headed by Doron Behar from Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, investigated the ancestral relation of the world’s Jewish communities (for an excellent in-depth analysis of both articles, please check out Razib Khan’s blog posts here and here).

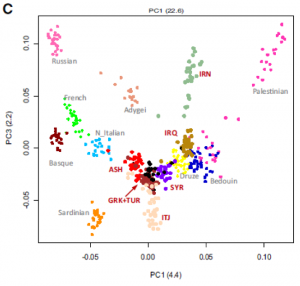

So what’s the elevator story on Jewish genetics? All of the Jewish groups examined showed admixing with local populations. This is not surprising. Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews seem to form one genetic cluster, while Iraqi and Iranian Jews tend to form another. Most importantly to the query at hand, a Jewish genetic signature does distinguish itself from the local gentile populations across the diaspora. That is, Sephardic, Middle Eastern and Ashkenazi Jews share common ancestry dating to over 2,000 years ago.

Figure 1: One of the Principal Component Analysis plots from Ostrer’s team’s work, showing grouping of Jewish populations (maroon lettering) compared to closely related gentile populations.

Back to that fateful night in Kissimmee – am I part of the “Hebrew People?” Well, yes and no. I share genes by descent with other Jews that stems from a Levantine population. The stem population no longer “exists” as a population in the biological sense, but instead branched into a wealth of culture, peoples and a genetic mark that can be found amongst those that happen to be born into this rather extensive Jewish family tree.

So how can I summarize who I am, genetically? I am a complex story of migration, bottlenecks, demographic explosions, reproductive isolation, proselytization and conversion. Every Jew is.

Atzmon, G., Hao, L., Pe’er, I., Velez, C., Pearlman, A., Palamara, P., Morrow, B., Friedman, E., Oddoux, C., & Burns, E. (2010). Abraham’s Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry The American Journal of Human Genetics DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015

Behar, D., Yunusbayev, B., Metspalu, M., Metspalu, E., Rosset, S., Parik, J., Rootsi, S., Chaubey, G., Kutuev, I., Yudkovsky, G., Khusnutdinova, E., Balanovsky, O., Semino, O., Pereira, L., Comas, D., Gurwitz, D., Bonne-Tamir, B., Parfitt, T., Hammer, M., Skorecki, K., & Villems, R. (2010). The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature09103