Studio portrait of models wearing traditional clothing from Salonika, Ottoman Empire. Left to Right: A married Jewish woman of Salonika; a Bulgarian woman of Perlèpè (Prilep); a married Muslim woman of Salonika. Photograph by Pascal Sébah in Osman Hamdi Bey’s “Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873,” from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal.

By Büşra Demirkol

In today’s modern world, the female body is a subject of discussion among politicians. Many politicians, like former president of the United States Donald Trump, have targeted the female body by attempting to restrict access to contraception and abortion. In 2016, Donald Trump stated that “some form of punishment” should be in place for women who receive abortions — though he later changed his mind and stated that only the person performing the abortion would be held legally responsible.

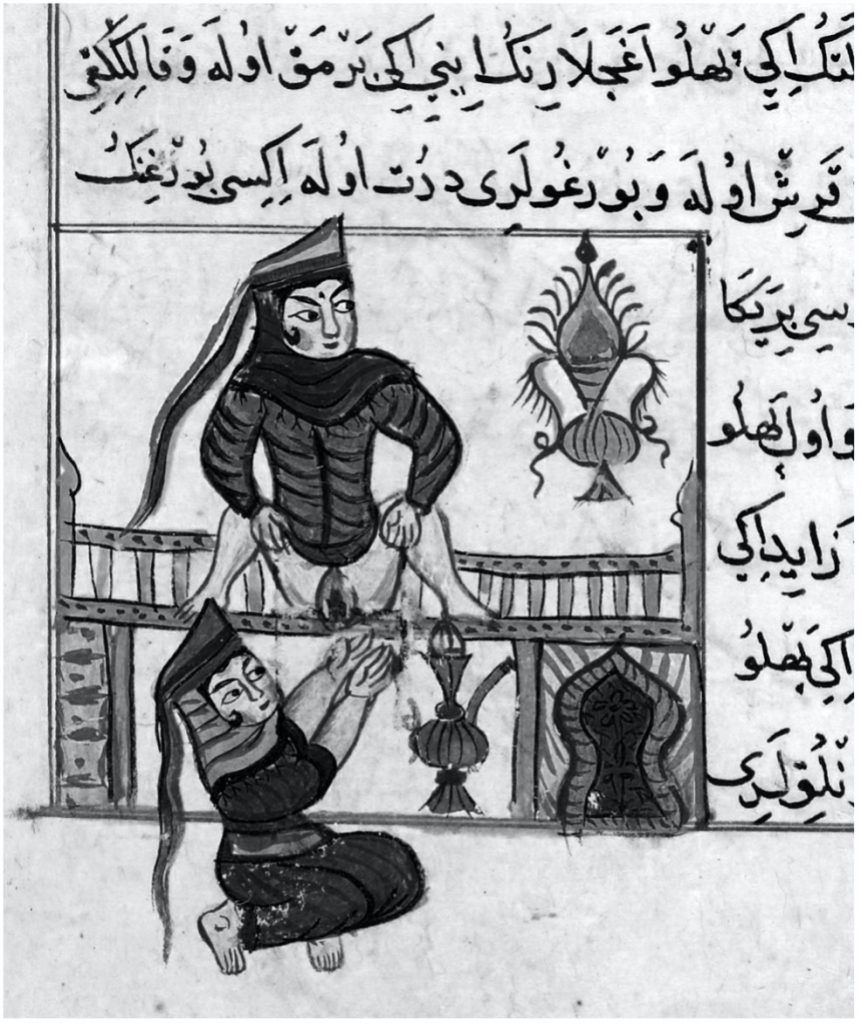

Illustration showing the midwife assisting a woman giving birth. From the Kitab al-Cerrahiyet al-Haniye (Royal Book of Surgery) by Şerefeddin Sabuncuoglu, written in 1465.

One might wonder whether politicians and other rulers throughout history have also tried to limit women’s ability to end unwanted pregnancies. The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is “no.” In Halakha, Jewish law, and in shari’a, Islamic law, as well, terminating a pregnancy — though discouraged — is recognized as a private matter that pertains only to the couple until the fourth month of pregnancy.

This means that in the Ottoman Empire, where Islamic law constituted one of the major pillars of legal culture, midwives — who would have helped Ottoman women to end unwanted pregnancies, in addition to delivering babies — enjoyed an autonomous and private working life for almost 500 years. It is worthwhile to remember that even in the 1400s, female midwives and surgeons were illustrated by Şerefeddin Sabuncuoğlu (1385-1470), a pivotal Ottoman-Turkish surgeon, in his book The Royal Book of Surgery.

How reproduction lost its privacy and midwives lost their autonomy

In the mid-19th century, population became a significant subject for state policies in the Ottoman Empire, due to demographic changes resulting from multiple wars, and major land and population losses within the empire. A growing interest by political authorities in women’s wombs started to jeopardize the traditional understanding of reproduction and childbearing as private acts.

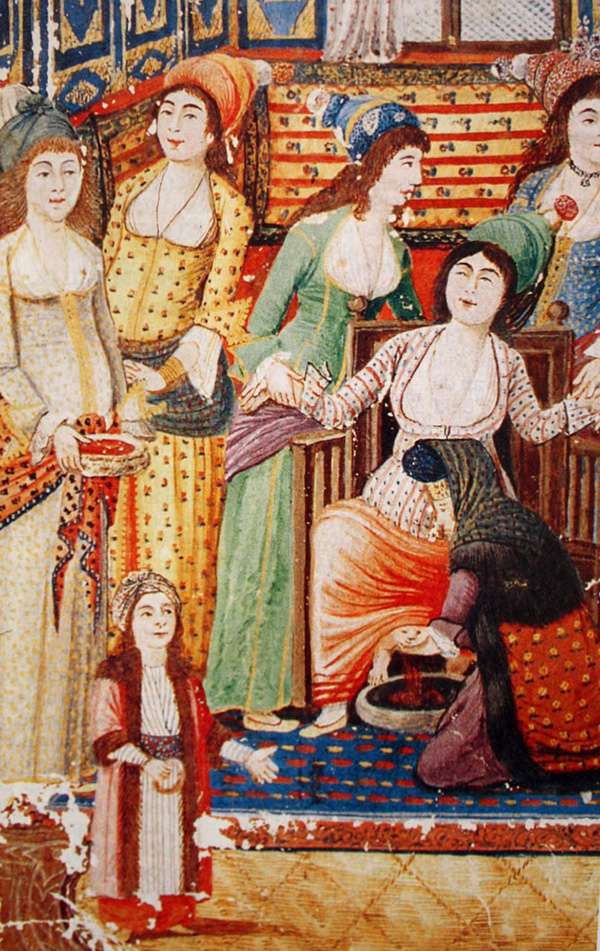

“Childbirth in the Mansion.” Source: Zenannâme (Book of Women) by Enderuni Hüseyin Fazıl, written in 1793.

During the 1800s, policies against the termination of pregnancy were one of the crucial tools for states on the verge of modernization to control women’s fertility. It is not surprising that midwives were simultaneously subjected to state surveillance, first by the criminalization of abortion and second by the medicalization of childbirth and midwifery — i.e., the requirement that only specialists licensed by the Ottoman Imperial Medical School be allowed to attend to women during childbirth.

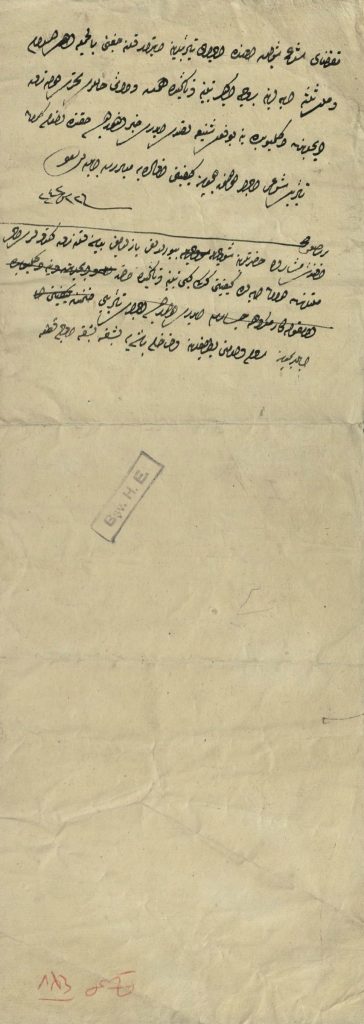

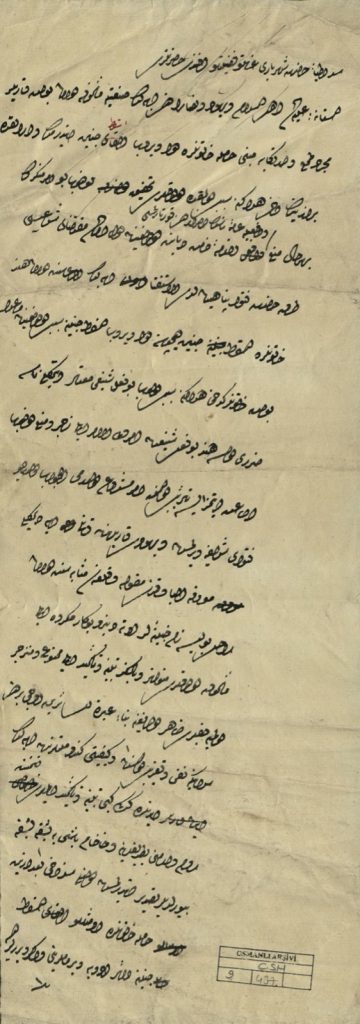

One of the most compelling examples of this targeting of midwifery in the Ottoman Empire occurred in 1827. An order from Divân-ı Hümayûn, the Imperial Chancery of State, to Hekimbaşı, the Chief Physician of the Imperial Court, declared that midwives from all four major religious communities — Muslim, Greek, Armenian, and Jewish — should not give abortifacient medicine to pregnant women. The subsequent lines in the order state that the punishment of anyone who contradicted the order was legally acceptable because “the protection of women is a compulsory requirement” for the state.

The document from the year of 1827 did not confine itself to warning about the upcoming regulations against abortion, but further announced that a Jewish midwife known to the public by the name “The Bloodstained Midwife,” and her assistant Rahil Polisa, were exiled to Salonica (Thessaloniki in present-day Greece), as a deterrent to others. According to the order, these two midwives were rumored to have been be involved in the “unpleasant act” (of abortion). It is stated that the midwives could not be prevented from carrying out abortions solely by being warned or admonished and therefore had to be exiled.

|

|

The 1827 order, from Ottoman State Archives. BOA, Cevdet Sıhhiye 437-12 S¸ 1242 Buyruldu.“..Yahûdî karılardan Katil Ebe dimekle ma‘rûf İlya Makzi(?) makûle ve kalfası mesâbesinden olan Rahil Polisa(?) nâm kimesneler öteden berü bu kâr-ı mekrûh ile me’lûfe oldukları mütevâtir ve yalnız tenbîh ve te’kîd ile memnû’ ve münzecir olamayacakları zâhîr olduğuna binâen ibretü’l-sâ’îrin üçün Selânik’e nefy ve ta‘zîb olunmuş..”

“On the grounds that İlya Makzi, one of the Jewish ladies known to the public by the name ‘Bloodstained Midwife’ and her assistant named Rahil Polisa have been rumored to be involved in this unpleasant act, and since it is obvious that they cannot be hindered and prevented by solely being warned or admonished, both of them were exiled and barred in Salonika, as a deterrent to others…” |

The story of two Jewish midwives: from fame to stigma

What made the example of exiling Jewish midwives cautionary for other midwives? Was it only the reality of the punishment, or did the fact that the order referred to the midwives’ ethnoreligious identity have a meaning for other midwives, as well?

According to the late Ottoman intellectual Abdülaziz Bey, until the 19th-century modernization of medical education by the state, Ottoman Jews were predominant in the field of both medicine and midwifery. Jewish midwives especially played a pivotal role in Ottoman folk medicine.

However, starting from the mid-19th century, the Ottoman state’s anxiety about its population — which led to the medicalization of childbirth and the criminalization of abortion — began to affect Jewish midwives too. In the heyday of pronatalism, in an era where the strength of the state was associated with the size of its population, the skill of Jewish midwives, known the most proficient and knowledgeable ones within the empire, started to be perceived as a threat.

In my current research, I explore how the traditional skill of midwifery, and the renown of Jewish women in the field, turned to stigmatization in the 19th century, as a result of a shift in the understanding of gender, sexuality, and science within the Ottoman Empire.

Disentangling this complex relationship reminds us that neither sexuality nor criminality were immutable notions, but rather socio-historical constructions. In that sense, I hope that learning about Ottoman Jewish midwives’ experiences with modernization in the past will make it easier to recognize, and to resist, intervention over women’s bodies, and professions, in the present as well.

Büşra Demirkol is a Ph.D. student the Interdisciplinary Program in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. She received her B.A. degree in sociology at Galatasaray University and her M.A. degree in Turkish studies at Sabanci University. Her master’s thesis focused on modernization in the legal field during the late Ottoman era and its impact on women on the margins. Based on penal codes, codification discussions and court records, she traces how marginal women were redefined and constructed within the boundaries of the public sphere in Ottoman legal culture, and were subjected to the state intervention according to a modern understanding of crime and punishment. Prior to graduate school, she also worked as a social worker with African, Afghan and Syrian refugees in Istanbul and conducted research about the official and unofficial schooling of Syrian children. Her general research interests consist of 19th century Ottoman social history, sociological theory, colonialism and nationalism, and women, sex and gender. Her work for the fellowship will focus on the modernization of the Sephardic community in the Ottoman Empire through two possible research axes, such as education and migration.

Büşra Demirkol is a Ph.D. student the Interdisciplinary Program in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. She received her B.A. degree in sociology at Galatasaray University and her M.A. degree in Turkish studies at Sabanci University. Her master’s thesis focused on modernization in the legal field during the late Ottoman era and its impact on women on the margins. Based on penal codes, codification discussions and court records, she traces how marginal women were redefined and constructed within the boundaries of the public sphere in Ottoman legal culture, and were subjected to the state intervention according to a modern understanding of crime and punishment. Prior to graduate school, she also worked as a social worker with African, Afghan and Syrian refugees in Istanbul and conducted research about the official and unofficial schooling of Syrian children. Her general research interests consist of 19th century Ottoman social history, sociological theory, colonialism and nationalism, and women, sex and gender. Her work for the fellowship will focus on the modernization of the Sephardic community in the Ottoman Empire through two possible research axes, such as education and migration.

Hello, I really enjoyed your article, and am currently researching Palestinian midwives after the midwife’s ordinance of 1929 focusing on the cultural history surrounding midwifery. I was wondering if I could get in contact with you to ask some further questions about your research. Thanks, Eloise

Hi Eloise, I would be happy to get in touch with you! Please feel free to contact me by email at bd092@uw.edu.