Nazi-translated documents in a Jerusalem archive reveal how the Rosenberg Task Force looted and repurposed Greek Jewish records during World War II.

By Joana Burger

In my dissertation, I explore how Greek Jews helped Jewish refugees who were fleeing the Nazis and became stranded in Greece. In the fall of 2021, in need of primary sources for my research, I traveled to the Central Archives of the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem to look at the records of the Jewish community of Athens.

From the archive’s website, I knew that this collection should contain the documents of the refugee relief committee established by the Jewish community of Athens in the 1930s.

Sitting in the reading room of the archive full of anticipation, surrounded by the dusty smell of old paper and with a mountain of files in front of me, I expected to find documents in Greek, Ladino, French and maybe even Hebrew – languages spoken by the Jews of Athens at the time. Little did I know that I was in for a big surprise.

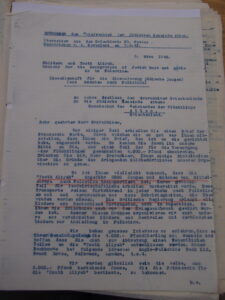

Image of a document from the Central Archives of the History of the Jewish People, collection GR-At Athens – Jewish Community

Upon opening the first box, I realized that the whole collection was in German. Page after page in neatly machine-tipped German script. Why would the Jewish community of Athens use German for corresponding and documenting their communal affairs?

Upon examining the documents more closely, I noticed that each page contained a header stating: “obtained from the correspondence of the Jewish community of Athens.” Underneath that line, each page provided the name of a translator and the original language of the document.

I was not holding the original collection from the Jewish community of Athens in my hands; I was looking at translations undertaken by the Nazis. The archival documents, which I was consulting for my research on Jewish refugees, possessed their own story of uprooting and dispersal.

When the Nazis occupied Greece in the spring of 1941, they not only targeted Jewish people, they also confiscated communal documents and cultural . The organizational entity responsible for this endeavor was the Rosenberg Task Force (German: Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg). In 1940, the Nazi regime established this task force under the command of the chief Nazi ideologue, Alfred Rosenberg to oversee the plunder of cultural artifacts in the occupied territories.

Looted documents in the cellar of the Institute for Research into the Jewish Question in Frankfurt, 1945 (https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/looted-jewish-cultural-materials)

Looted items and archival documents were transferred to Germany to facilitate the Nazis’ antisemitic pseudo-research on “the Jewish race.” To this end, Rosenberg established the Institute for Research into the Jewish Question (German: Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage) in Frankfurt in 1941. Once the Germans invaded the Balkans in the spring of 1941, the Rosenberg Task Force transferred to Greece, where it confiscated cultural artifacts of Greek antiquity and looted the archives of Greece’s Jewish communities.

Upon arrival in Athens, the Rosenberg Task Force established a translation and evaluation office. Under the oversight of Dr. Helmut Böttner, German staff, Greek collaborators and a Greek University professor worked for over three months to translate the looted documents from Greek, French and Ladino into . In total, they translated, typed and sorted over 1,400 documents that had been stolen from several Jewish and non-Jewish organizations, including the Jewish community of Athens, the B’nei B’rith Lodge, the Jewish emigrant office in Athens, the Zionist association of Athens, the Zionist Women’s Association (WIZO), and the Greek Freemasons.

What prompted the Nazis to engage in the painstaking effort of translating and typing these documents prior to their shipment to Germany?

Nazi officers on the Acropolis in Athens

I found the answer to this question in the “Final Report about the Activities of the Rosenberg Task Force in Greece,” which was commissioned by Alfred Rosenberg and sent to Germany in November 1941. According to the report, translating the documents in Greece was necessary because they were of imminent political importance and shipping them to Germany would have taken too much time. Furthermore, Rosenberg doubted that they would have found skilled translators for the relevant languages in Germany.

In the vein of the Nazis’ antisemitic conspiracy theories, the translation and evaluation effort aimed to “uncover the anti-German activities of the Freemasons and international Jewish organizations in Greece.” The report particularly emphasized the role of Greek Jews in facilitating the escape of Jewish refugees. Böttner and his team claimed to have uncovered that “Greek Jews provided valuable help to World Jewry regarding the transfer of large numbers of Jewish refugees from Central Europe to Palestine by legal or illegal means.”

Sitting at the archives in Jerusalem eighty years later, I found myself looking at the history of the Jewish community in Athens through the gaze of the Nazis. Wrested from their original archival context, these sources had been re-organized by Dr. Böttner and his team based on their antisemitic research agenda and distorted through the translation process.

On the one hand, I felt like I was holding the violated shreds of the Jewish history of Athens in my hands. Yet on the other hand, the fact that the documents were translated into German and machine-typed facilitated my research. While I can read Greek, Hebrew, Ladino and French, I am a native speaker of German.

My eyes flying over the pages of Nazi translations, I was overcome by the eeriness of my own ease in reading these files. And not only that — Rosenberg’s and Dr. Böttner’s conspiratorial interest in Greek Jews’ support for Jewish refugees aligned with my own research focus on Jewish aid networks. How could I use these sources for my research? Could I look beyond the distortion of the translations?

Several years have passed since I first encountered this archival collection of Nazi translations. In the meantime, I have traveled to additional archives in Greece, Israel and Washington, DC, where I have found a plethora of sources concerning Greek Jews’ refugee relief work.

Besides the original documents from the refugee relief committee in Athens, I have also collected personal documents such as correspondence and memoirs written by refugees themselves. This additional archival material facilitates a multifaceted view on the question of Greek Jews’ refugee relief work. It allows me to “detach” the Nazi translations from their immediate archival context, which was created by the Germans, and to re-contextualize it as documentation of Athenian Jews’ humanitarian aid.

Most stories in these personal documents remain fragmented and provide only a snapshot of the human tragedy behind the writing. From notes of gratitude to letters of complaint – sent by refugees to the refugee relief committee in Athens – I am piecing together a mosaic of Jewish solidarity at the precise moment when fascism challenged Jews’ belonging to European nation-states.

Although I only have the Nazi translations from that particular collection from Athens – the originals are lost – my additional archival research is helping me to unearth the authentic voices of the authors.

Joana Bürger researches Jewish refugees in the eastern Mediterranean during the interwar period. She earned a BSc in Psychology from Potsdam University in Germany and an International Research MA in Middle Eastern History from Tel Aviv University in Israel. Her master’s thesis examined Greco-Jewish identity formation in early 20th-century Corfu and Athens. Joana gained experience with digital approaches to Holocaust remembrance while working as a translator for the oral history project “Memories of the German Occupation in Greece,” a collaboration between Freie Universität Berlin and the National Kapodistrias University of Athens. Her research interests include modern Mediterranean Jewish history, migration in the eastern Mediterranean during the interwar period, and comparative Holocaust memory.

Joana Bürger researches Jewish refugees in the eastern Mediterranean during the interwar period. She earned a BSc in Psychology from Potsdam University in Germany and an International Research MA in Middle Eastern History from Tel Aviv University in Israel. Her master’s thesis examined Greco-Jewish identity formation in early 20th-century Corfu and Athens. Joana gained experience with digital approaches to Holocaust remembrance while working as a translator for the oral history project “Memories of the German Occupation in Greece,” a collaboration between Freie Universität Berlin and the National Kapodistrias University of Athens. Her research interests include modern Mediterranean Jewish history, migration in the eastern Mediterranean during the interwar period, and comparative Holocaust memory.