American Jews in front of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement building in Manhattan. Via the Jewish Daily Forward.

By Kathie Friedman-Kasaba

World history has given Jewish Americans, and all Americans, plenty of reason for anxiety about the Trump administration’s current immigration policies.

As a scholar of international refugee studies, I have researched how the use of dehumanizing language — by politicians, political parties and the media — paves the way for denying compassion and then protection to people fleeing violence.

The Trump administration’s practice of criminally prosecuting every adult who crosses the southern border to the U.S. without prior authorization, even if they are fleeing life-threatening persecution, is built on just such a foundation of dehumanization.

President Trump’s recently upheld ban on travel from mostly Muslim countries is similarly based on nearly two decades of the demonization of a religion, going so far as to deny war refugees from Syria sanctuary from extreme ethno-religious violence.

Though the United States is often represented as a safe haven for the world’s most vulnerable and persecuted populations, there are eras when this promise rings hollow.

A history of xenophobic immigration restrictions

American immigration policy in the early 20th century was constructed in accordance with the ideology of racial nativism, defined by historian John Higham as “the intersection of racial attitudes with nationalistic ones — in other words, the extension to European nationalities of that sense of absolute difference which already divided white Americans from people of other colors.”

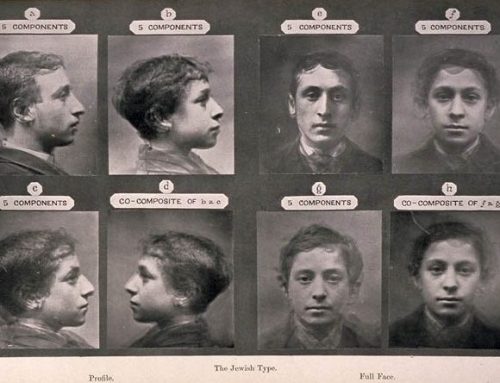

The United States Immigration Commission, formed by Congress in 1907, concluded that immigrants from eastern and southern Europe — including Russia, Hungary, Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece — posed a serious threat to America because of their genetically inherited inability to assimilate into American society.

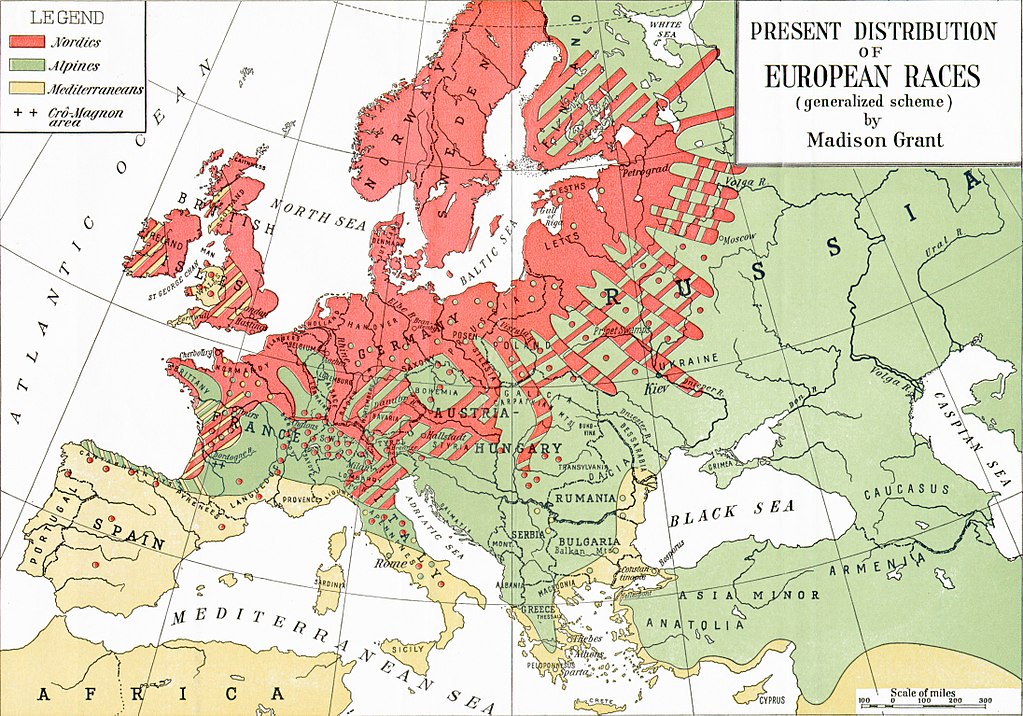

Image from Madison Grant’s “Passing of the Great Race,” showing his view of how superior “Nordic” peoples were distributed in Europe

President Theodore Roosevelt laid the groundwork for the Commission’s conclusions by characterizing immigrants from eastern and southern Europe as all “people of bad character.” Senator Henry Cabot Lodge compared them to “the great influx of barbarians into Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire.” Madison Grant, close friend to Roosevelt and author of The Passing of the Great Race, one of the most famous books of scientific racism, argued for halting the immigration of non-Nordic populations, which he characterized as “criminal,” “diseased,” and “worthless race types.”

Despite the flight of Eastern European Jews from the violence of pogroms and religious persecution, the Commission’s findings supported a drastic reduction of the quota for individuals from those world regions. This rigid quota system, and the xenophobia behind it, was responsible for America’s refusal in 1939 to admit 20,000 mostly Jewish children from Germany and Austria fleeing the Nazi regime, along with nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees who had traveled close to American shores by boat the same year.

The National Origins Act of 1924 — intact throughout the lead up to, during, and immediately following the Holocaust — was replaced only when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, a consequence of the U.S. Civil Rights movement, established a system based on an immigrant’s skills or family relationship with a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident.

Current challenges to accepted refugee law

The United States’ humanity and compassion in protecting vulnerable refugees is again being tested. Donald Trump put the world on notice when, at the start of his campaign, he used criminalizing and dehumanizing language to describe people crossing the southern border of the United States, whom he characterized as rapists and drug dealers.

More recently, he used similarly dehumanizing language to describe “people coming into the country” from the southern border, saying: “These aren’t people, they are animals.” The Democrats, he charged, want “illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our country, like MS-13.” Again, the accusation of sub-human criminality against immigrants by a sitting President, similar to the politically motivated rhetoric of Theodore Roosevelt’s administration.

Let’s be clear about who exactly is being targeted with this language. What we are currently witnessing is primarily the flight from violence of Honduran, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran families through Mexico and across the border into the United States. Most families, victimized or threatened by gangs, are asking for asylum.

According to the United Nations Refugee Convention, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the US Refugee Act of 1980, it is not illegal to cross a border without prior authorization to ask for asylum, that is, for protection on the grounds of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. That right has been one of the most cherished principles of both the international and the U.S. refugee system that was created following the Holocaust, and it owes its existence in part to international guilt over failing to protect people from the violence of fascism and the Holocaust.

Moreover, U.S. and international refugee law prohibits forcibly returning people to countries where their lives are in danger. It is a moral obligation to protect people in harm’s way. This obligation, and the refugee system, are both violated by criminally prosecuting asylum seekers who seek protection, including victims of domestic or gang violence.

A travel ban recently upheld by the Supreme Court also had its beginnings with the dehumanization and criminalization of people, including Syrian refugees fleeing for their lives from Russian barrel bombs and the Syrian government’s chemical attacks. Decades of politicians and pundits smearing all Muslim co-religionists, as national security threats unable to assimilate into American culture, paved the way for this policy.

During his presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on,” in spite of the two-to-three year-long vetting system that was already in place. The power of the President to reframe religious affiliation as threat to national security reigns.

An opportunity to stand up for immigrants and refugees

The unease and apprehension of the American public persists as many questions go unanswered. Will the 2,300-plus Central American children who were forcibly taken from their parents by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and turned over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) be reunited with their families, and how long will that take? Will the travel ban be temporary or permanent? Will the attack on the immigration and refugee system continue through the November elections, and then end? Or is the American public witnessing a new era of zero-tolerance in recognizing the humanity in all of us?

The United States must be reminded of those times when it welcomed immigrants and refugees who needed protection from violence. Jewish Americans, and all historically dehumanized minorities, must use their legacy to fight on behalf of the humanity of others.

Everyone has an obligation to speak out against the attacks on U.S. immigration and asylum programs, and to stand up and support others who are experiencing danger and persecution. The United States should embrace all human beings, no matter where they are from, with the same compassion and respect, rather than falling back into its history of xenophobia.

Kathie Friedman-Kasaba is Associate Professor of International Studies and Jewish Studies in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She teaches and publishes primarily in the areas of refugee and immigration studies. Her current book in progress, based on more than 100 interviews with refugees and their adult children, is titled “The Afterlife of Ethnic Cleansing: How Refugees Re-define Belonging and Citizenship.”

Kathie Friedman-Kasaba is Associate Professor of International Studies and Jewish Studies in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She teaches and publishes primarily in the areas of refugee and immigration studies. Her current book in progress, based on more than 100 interviews with refugees and their adult children, is titled “The Afterlife of Ethnic Cleansing: How Refugees Re-define Belonging and Citizenship.”

Our president and his supporters, including the Supreme Court are committing acts of treason and should be punished for doing so. Yet it seems as though our system of checks and balances has fallen by the wayside. No one is minding the store.