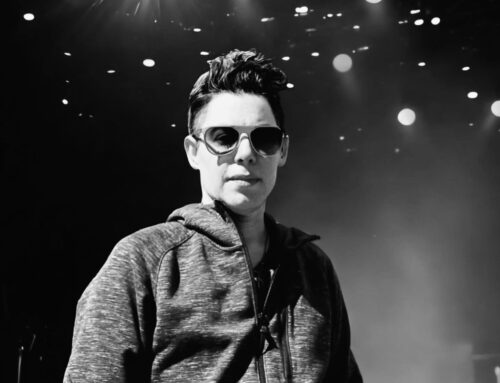

Prof. Paul Burstein has been at the UW since 1985 and chaired Jewish Studies from 2003-2008. Pictured here at the Jewish Studies 2013 Year-end Celebration. Photo by Meryl Schenker.

Editor’s Note: This fall Prof. Paul Burstein is retiring after three decades at the University of Washington. He began teaching here in 1985 and served as chair of the Stroum Jewish Studies Program from 2003-2008. In this new interview, Prof. Burstein shares some reflections about his field of sociology, the state of higher education, and the history of Jewish Studies on campus. Join the Stroum Center on Oct. 23rd at a special reception and lecture to honor Prof. Burstein (click here for info!).

HP: As a sociologist, you must have an opinion (or several!) about the Pew Research Center’s “Portrait of Jewish Americans,” which caused quite a stir when it was published last year, and other recent research. Care to share?

PB: The Pew study is especially interesting because it’s one of the few major studies of Jews not conducted or financed by Jewish organizations. A couple of key take-aways: Contrary to what so many people believe, the number of Jews in the U.S. is going up, not down. Yet at the same time it’s becoming more and more challenging to define who is a Jew and what that means. How are we to understand the role in Jewish life of non-Jewish spouses in mixed marriages who actually contribute more to the Jewish education of their children and to the Jewish community than their “officially” Jewish spouse?

Probably the most important long-term high-quality study of Jewish life in the U.S. is the work on Birthright Israel being done at Brandeis. The director of the study, based on his own previous work, knew Birthright couldn’t possibly succeed. But it has! There are major long-term impacts on the participants and on their Israeli guides. And now we’re studying the parents of those who participate; they’re involved too!

HP: What’s most important about Jewish Studies as an academic field in secular universities?

PB: It normalizes the Jewish experience, showing that Jews aren’t strange perpetual outsiders, but regular people, just like all the other people we study in universities—like the French, the Chinese, or the Swedes. You don’t have to be Chinese to find China interesting, and you don’t have to be Jewish to find Jews interesting. Most students in Jewish Studies courses aren’t Jewish (even in New York), and neither are some faculty. Jewish Studies, a field which barely existed a few decades ago, is now taught at hundreds of universities in the U.S., and it’s how we show everyone—Jews and non-Jews—who we are. What a wonderful opportunity!

HP: How did you first get involved with Jewish Studies? How did UW Jewish Studies evolve and grow during your leadership of the program?

PB: My dissertation was on politics in Israel, but I wasn’t involved in Jewish Studies until Joel Migdal got me involved here. I was amazed to discover that as of the 1990s, the UW didn’t have a single course teaching about the overall Jewish experience in the U.S.—so I started teaching one. Then one day I found myself Chair of Jewish Studies, and also doing research on Jewish organizations and Jewish economic success.

I became chair in 2003 at a very difficult time. We had wonderful faculty all around campus, but they were all volunteers—no one was paid for teaching Jewish Studies—a very tiny budget, and almost no staff. We taught hundreds of students a year and did a lot of outreach, but the larger community barely knew we existed.

We had to convince the Jewish Federation—the source of almost all our funding at the time—that what we were doing was worthwhile, the Jewish community that Jewish Studies was a real field, not “Hebrew school for grownups,” and the UW that we could raise funds, as everyone was being forced to do because of declining support from the legislature.

With the enthusiastic help of many colleagues, I helped create a real infrastructure to support teaching, research, and outreach to the community. We hired our first real Jewish Studies faculty member (in the sense that he got paid by Jewish Studies), Noam Pianko—a great beginning! We hired our first-ever professionally trained staff person, Jennifer Cohen, who got us organized. And we followed up on the efforts of the previous Chair, Kathie Friedman, to create an Advisory Board; Herb Pruzan’s agreeing to be the first Chair made a huge difference, and today Jewish Studies at the UW just couldn’t exist as it does without the support the Advisory Board provides.

HP: What’s been a major change you’ve seen at the UW in general over the last 20 years?

PB: The biggest change is the withdrawal of public funding, which makes it more and more difficult to provide quality education to our students. We have to spend a huge amount of effort fundraising instead of teaching, research, and reaching out to the community. But in the face of all this change there’s one important thing that hasn’t changed, remaining stable to an extent that astonishes me—the dedication of our faculty and staff, whose commitment and effort are astounding—especially considering that most of the faculty are still essentially volunteers.

HP: Congratulations on becoming an Emeritus Professor! What projects are you working on now?

PB: Right now I’m studying Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings on the Middle East going back to 1948. It relates to what I published in my recent book on congressional response to the public (Cambridge University Press, 2014). Is there an all-powerful “Jewish lobby,” as some say? In our dreams, maybe; in real life, no.

I plan to continue to do research in Jewish Studies, and I hope to remain actively involved in campus life. I promote social science at the Association for Jewish Studies, and the study of Jews at the American Sociological Association. I think I’ll be able to keep busy.