Students and field staff hold up the flag of the Roman 6th Legion “Ferrata” at the end of 2023 excavations in the legionary principia

New Stroum Center faculty member Mark Letteney is an ancient historian and archaeologist working in the history of incarceration, book history, and the archaeology of military conquest and administration. He joined the UW’s Department of History in the fall of 2023.

In addition to his research and teaching, Mark serves as assistant director on the excavation of the Roman 6th Legion at Legio, Israel, where he directs excavations in the legionary amphitheater, and is co-director (with Matthew J. Adams) of the Solomon’s Pools Archaeological Project. Mark will be leading UW student trips to participate in archaeological digs at the site he oversees in Israel.

Below, Mark answers questions about his work with archaeology, its connection with Jewish history, and the opportunities presented in working with students.

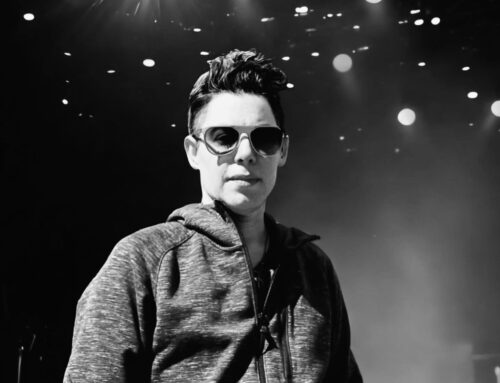

Portrait by Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong

How did you come to be interested in archaeology?

It all happened on something of a whim; I was living in Germany and finishing my master’s degree at Yale when the university advertised a prize for students interested in field research. I was hoping to pursue a career in history and had settled on what historians call “materialist methods” as my preferred lens. At 23, I thought, “what’s more ‘material’ than dirt and ceramics?”

Really, there wasn’t too much thought beyond that. I received the prize, signed up for an excavation at Tel Megiddo in Israel, and flew to Tel Aviv for a four-week field school in which I learned the basics of field archaeology, the nuts and bolts of archaeological documentation, and an approach to history that I had been craving. From there, well, from there it got out of hand — I spent nearly every summer from then on in Israel, taking part in archaeological survey and excavation, and moving from learning to teaching field school for other interested students.

Why is archaeology important?

Archaeology is important because it deals primarily in trash. Let me explain what I mean: as a textual historian, sitting in my office, going to the library, or working in manuscript archives, I have access primarily to materials that have been purposefully preserved: books and narratives which one generation intended to pass on to the next. Reading and understanding these texts is immensely important, but rarely in such narratives can we access the “everyday” of ancient people’s lives.

Mark Letteney and 2022 area assistant Thomas Keep overseeing excavations in the legionary amphitheater

Archaeologists are trained in understanding what is left over, mostly unintentionally, from ancient people’s lives. Trash heaps and toilets and broken pots and pans underneath the collapsed wall of a house are a goldmine if you want to know how people actually lived. Still today, we keep our old diaries, but we throw out our coffee receipts and worn-out shoes because they don’t contain information that we might want to access in the future. But to an archaeologist, that information about how you actually spent your day is at least as important as the narrative of your own life that you left in your diary. Archaeology helps us to see that the ancient world was in some ways utterly foreign to our own, and in other ways, eerily similar.

How does your work at the dig sites fit into your teaching and current research?

Ancient history at the UW has always focused on teaching history “from below” — the history not only of poets and emperors but of everyday people: soldiers, farmers, enslaved people — we’re interested in cogs in the machinery of ancient empire as much as the movements of that machine. Mixing archaeological with literary approaches allows students to see a broader vista of antiquity, in dazzling color.

Fragment of a roof tile, stamped with the name of the 6th Legion “Ferrata” (“Ironclad”)

How does your research and archaeological work interface with Jewish history?

I came to archaeology with an interest in Roman history, and especially an interest in the infrastructure of Roman occupation. The year after my field school at Megiddo I joined a team who had just begun excavating a Roman army base in the Jezreel Valley (lower Galilee). The site is fascinating. Not only is it the only full-sized legionary base known in the Eastern Empire, but just outside its walls is a service village in which Jews, Samaritans, Christians, and Pagans lived side-by-side already in the third century CE. I began in 2016 as co-director of the Solomon’s Pools Archaeological Project, a water installation from the early second century CE which was built to funnel winter rains from the Judaean hills north to Jerusalem. The site was in use from the second century CE through the 1960s, and it had never been excavated.

Through excavation we established that the site, like the legionary base at Legio, was a monument of military occupation — it was built by the Roman army as part of the re-founding of Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina, a Roman city built on the ruins of Jerusalem, excluding Jews. In these immense ancient infrastructure projects, we see the mechanics of occupation. And, through excavating the homes of those living just outside of a site of Legio, we glimpse the lives of locals negotiating a new world under a foreign and violent regime.

2023 excavations in the gate of the legionary amphitheater

What are your hopes for leading students on digs at the UW?

I am delighted to have the opportunity to bring students to Israel to learn the science and craft of field archaeology. I hope that they return to Seattle with a new understanding of the lives of ancient people who lived and worked in these spaces millennia ago and have a strong understanding of the wide variety of peoples and places that are still attested archaeologically at sites across the country. Before we embark on excavation at Legio, students will spend five days exploring Bronze and Iron Age sites to see the earliest evidence of complex societies in what is now the land of Israel, before examining Roman, Byzantine, Mamluk and Ottoman sites which add to the rich history of the space, and in many cases still define the way that we think about the land today.

What is the most interesting thing you’ve discovered on a dig?

This is a tough one, because as an archaeologist I want to say that “things” are not interesting outside of their immediate archaeological context — we could find the Ark of the Covenant, and if it weren’t excavated slowly and methodically in a way that explains how it got to be there and why, then it would be of near-zero value archaeologically.

Nevertheless, the most fun I’ve had in the field, believe it or not, was excavating a toilet. To pre-empt the inevitable question: no, there is no smell or danger from 1800-year-old material. But there is data that can tell us what kind of diet soldiers had. A toilet is a goldmine if you’re trying to get at the “everyday” of ancient lives.